This chapter focuses on an investment manager’s culture, investment approach and objectives, investment policy, time horizon, asset classes and governance.

There are important distinctions between a manager’s firmwide investment process or approach and how a product is governed. An asset owner may identify desirable firm-level ESG practices that are aligned with its investment strategy and policy, but if it selects a product where ESG factors are ignored or not aligned with broader aims and objectives, the ESG and investment impact will be limited, nulled or negative. On the other hand, if selecting what appears to be a well suited ESG product or ESG integrated mainstream fund from a manager that lacks a high-level strategic policy and cultural commitment to incorporating such factors, an asset owner would need to question if that product has the long-term institutional support to survive. Asset owners also need to be wary of potential future style drift of a chosen product.

Culture

Culture is one of, if not the, most important element to consider when selecting an external manager. In this context, culture represents a set of habits, codes and expectations that govern how an organisation invests, regardless of its size and geographical location. If there is no cultural fit and understanding of ESG factors between an asset owner and a potential manager, there is little fundament to establish a long-term investment relationship.

However, culture is an ambiguous concept. Questions about manager ownership and management alignment with the incentive structures, beliefs and values of decision makers – beyond their technical competencies – are key components to assess. For example, it is important to find out whether a firm’s culture is distribution led, with incentives related to asset accumulation, or investment led, with incentives reflecting investment outcomes. Assessments should reveal how “cultural outcomes in firms [need to] embody respect for public interest objectives”, as cited by the FCA’s CEO, Andrew Bailey, at the HKMA Annual Conference for Independent Non-Executive Directors in March 2017. We recommend that all selection processes culminate in onsite meetings, with asset owners meeting the prospective manager’s team to gauge cultural fit. Regardless of whether a consultant is used in the selection process or an asset owner works independently, culture must be addressed in all Requests for Proposals (RfPs).

Investment approach and objectives

Questions on investment approach and objectives should shed light on how a manager produces value through ESG insight. Understanding the business and investment philosophy of a prospective manager enables asset owners to ascertain whether such an approach is in line with their own objectives.

Investment objectives usually differ across managers, strategies, funds and products. Asset owners will encounter high-level statements and more specific objectives closer to the product level during the selection process. The most straightforward approach would entail ESG incorporation being part of a management firm’s overall investment objectives and reflected across all activities and products. This might include a mission statement, an outline of thematic investment strategies and active ownership objectives, and an ESG benchmark for a manager’s operations.

The selection process is more complex when ESG factors are not explicitly expressed in investment objectives. It is possible, although rare, that a management firm that does not express ESG commitments in high-level objective or approach statements still uses ESG insight in investment decisions. To avoid greenwashing, however, asset owners should ascertain how high-level approach and objectives statements that include ESG considerations are operationalised across the firm and employees.

If an asset owner’s investment strategy does not align with a manager’s firm-level objectives, the asset owner must reconsider whether to grant a mandate. As previously discussed, assessing investment approach and cultural fit is crucial and can be reinforced by reviewing policies (more on policy below). For example, a fund that measures its carbon footprint without aiming to mitigate portfolio risk in a +2 degrees scenario might be unsatisfactory for an asset owner that strives to have a positive real economy influence in line with associated targets.

Investment policy: Codifying a strategy

Asset owners should implement their investment policies and develop risk management, asset allocation and mandates accordingly. An investment policy should reflect an asset owner’s strategy and views on best practice in managing investments, including incorporating ESG factors. See the PRI’s Investment policy: process & practice report for further guidance.

It is important to establish whether a manager’s firm-wide investment policy reflects internal stakeholder consensus. However, it is not uncommon for a management firm to have more than one investment policy; a multi-asset, multiapproach firm may be unable to formulate a single policy that can serve its entire client, asset and product base. For multi-asset offerings, more detailed policies are often found at the strategy, business line and product levels. Policies and term sheets, fact sheets, fund operational documentation, risk management frameworks and marketing materials often overlap. At a specialist, more narrowly-focused manager, policies are likely to be expressed at the firm level.

A written investment policy should define what ESG means to an investment manager in practical terms. While strong cultures may override weak policies, it is vital that policies are recorded and endorsed by the board and CEO. An assessment of the policy should indicate whether it is compatible with an asset owner’s ESG-related definitions and expectations.

Any conflicts detected may be significant and result in selecting a different investment manager, or establishing terms during the appointment phase (for an example in private equity, see the PRI’s Incorporating responsible investment requirements into private equity fund terms guide).

Asset owners should compare the policies of prospective managers, which is not always an easy task as they must assess how managers address ESG factors as well as how policies are adhered to. Policies that marginalise ESG considerations, or institutions that have separate ESG policies, may compromise the depth of delivery across the firm on related objectives. However, a firm with a strong culture of long-term independent and analytical thinking might be a better fit than a firm with a well formulated policy, but no relevant cultural commitment.

Investment time horizon

An asset owner’s ESG-related objectives should translate into investment decisions with appropriate long-term time horizons. For example, it can be difficult to achieve positive real world impact and reap competitive returns with a highturnover, short-term product as ESG factors tend to play out over a long period of time. This also holds true culturally; for example, short-termism can manifest in unnecessarily heavy trading patterns reflecting a firm’s management style.

While short-term metrics may be relevant at times, shorttermism is neither desirable nor conducive to responsible investment. High churn is likely to complicate active ownership and make any positive real world impact or ESG risk reduction difficult to monitor. Asset owners must be aware of this when selecting managers. For more information, see the PRI’s How asset owners can drive responsible investment - Beliefs, strategies & mandates paper.

Investment process rigor and product integrity can ultimately only be explored post-fact and by the asset allocation decision itself. It is also important to remember that cultural fit may not guarantee long-termism; asset owners must remain critical of themselves and how they conduct manager research.

Asset classes

An investment manager may not have the same level of ESG competency across all asset classes. Managers’ firmlevel practices may also not be fully suitable for all asset classes due to style, culture or resources. Asset owners should therefore ascertain how managers use ESG insight across asset classes. The extent to which ESG principles are embedded across the organisation may highlight cultural and/or staff competency deficiencies in less established asset classes. When selecting an investment manager, asset owners should first look at the firm’s overall ESG alignment, then its capability in a specific asset class, and then a choose a suitable investment product. ESG capabilities related to specific asset classes within a mandate must be evaluated.

Governance and organisational architecture

A firm’s approach to investment governance will depend on its culture, style and size. Certain investment approaches may also require a specific set-up of resources that needs to be observed. For example, with quantitative and screendriven investments, the ESG function might be outsourced. Sound governance ensures that a firm’s investment approach is embedded throughout the organisation.

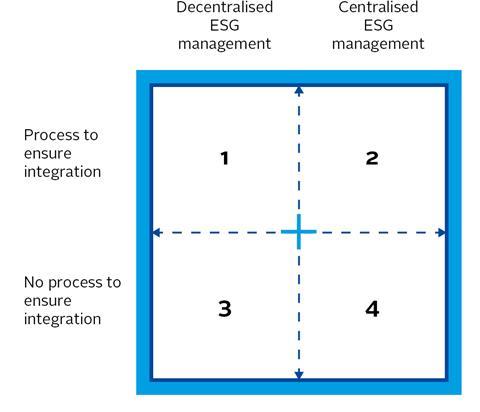

As the figure below shows, a dedicated ESG team (i.e. centralised structure) can be responsible for day-to-day ESG incorporation.

Alternatively, all investment team members might contribute to ESG insight and incorporate ESG factors into decision making – also known as the integrated model or decentralised structure. Meanwhile, many firms have adopted hybrid solutions combining elements of both. Governance transparency and quality of the chosen structure is crucial and it is not possible to rank one above the other (centralised versus decentralised) as a guarantee of robust ESG incorporation. According to research by the Investor Responsibility Research Center Institute (IRRCi), the management dimension of ESG incorporation is fundamental to integration, ultimately determining its quality. Strong policies safeguard ESG incorporation integrity regardless of organisational architecture.

Further information on organisational design choices in ESG integration can be found in A practical guide to ESG integration for equity

Asset owners need to understand how investment managers add ESG value across all their activities, and whether there is a reasonable expectation that the governance process is conducive to the owner’s ESG objectives. For example, if the compliance, sales or marketing team oversees ESG-related matters, individuals in the team must have the requisite competency and authority to incorporate and analyse ESG factors.

Investment managers may also partly or fully outsource their ESG activities using ESG indices, ratings, consultants and engagement service providers in different stages of the investment process. Therefore, evaluating a manager’s resources should extend to the quality and suitability of its external vendors as a regular part of operational due diligence.

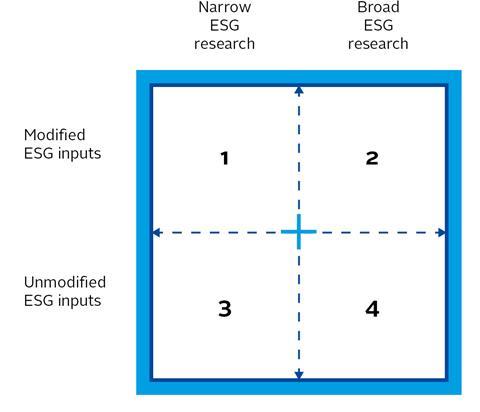

If a manager outsources a component of its ESG understanding to an external partner, it is important to verify whether that manager is able to modify, monitor and control those inputs.

The stability of external relationships is also an issue for asset owners looking for a long-term relationship. As firm-level ESG resourcing decisions are likely to filter down from the organisational level to the product level heterogeneously, it is important to discuss preferred approaches at the most appropriate level.

Download the full report

-

Asset owner guide: Enhancing manager selection with ESG insight

March 2018

Asset owner guide: Enhancing manager selection with ESG insight

- 1

- 2

Currently reading

Currently readingGaining a high-level view of prospective management firms

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6