Matilde Faralli, Imperial College London

Modeling beliefs about climate risk is a challenging task. It involves assessing the interplay between physical risks, such as natural disasters, and transition risks associated with carbon reduction policies.

In recent work, I examined how exposure to extreme weather events affects equity analysts’ earnings forecasts. This setting was ideal for studying how climate affects expectations, because equity analysts are key producers of financial information (Mikhail, 2007) and are required to issue timely forecasts. Analysts do not just use publicly available information; they also incorporate their own subjective beliefs about climate risks.

To discern how weather events affect analysts’ climate beliefs, I investigated the relationship between weather events and changes in forecasts, while also controlling for weather shocks that do not impact firms’ earnings. If, after such a weather shock, an analyst changed their forecast, it must have been the case that the change in forecast was driven by a shift in the analyst’s beliefs.

There are two possible reasons why an analyst might change their forecast after a weather event that does not affect earnings. One possibility is due to new insights about the future economic costs of climate change, obtained from exposure to salient weather events. According to this information hypothesis, exposure to extreme weather events has a positive effect on an analyst’s ability to forecast firms’ climate risks. If this is the case, exposure to climate events will be associated with a reduction in analysts’ forecast errors.

Alternatively, exposure to an extreme weather event might have an emotional impact and influence analysts’ risk-taking behavior. According to this heuristic hypothesis, exposure to weather events can result in overestimating climate risks, potentially improving analysts’ forecasts in cases where analysts are initially overly optimistic. However, a heuristic effect would not lead to a differentiation between firms with high or low climate risks as analysts would, on average, downwardly revise forecasts for all firms.

What drives analysts’ beliefs?

To understand what drives analysts’ beliefs, I built a comprehensive dataset with analysts’ and weather shocks’ characteristics. Salient weather shocks are defined as natural hazards that result in at least 100 injured people, 10 fatalities, or US$1 billion in economic damages (sourced from the Storm Event database, NOAA). I then collected information on analysts’ office locations and classified them into two groups: (i) those who had been exposed to a salient weather shock for the first time and were located within 100 miles of the affected area and (ii) a control group. The control group included both analysts who have never been exposed to climate events (never treated) and analysts who, in a given period, have not yet been exposed to a weather shock but will be exposed in the future (yet-to-be-treated). To ensure that the event did not affect firm earnings, I only considered firms with locations more than 100 miles from the event.

To understand the drivers of analysts’ beliefs, I compared the forecast accuracy of both analysts located near and distant from weather events, looking at the absolute value of the difference between firms’ actual and forecasted earnings (scaled by the stock price in the period preceding the event).

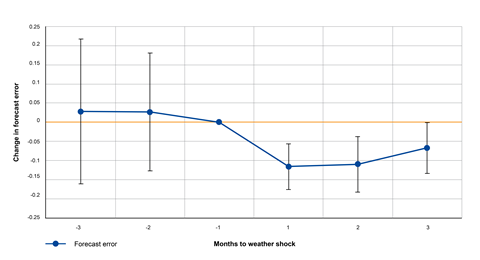

Figure 1 below focuses on a six-month window around the event and plots the change in analyst forecast errors between the treated and control groups (the forecast errors of the two groups are rescaled so that they are equal one month before the event t=-1). The figure shows that exposure to weather events reduces forecast errors with an improvement in accuracy that lasts for up to three months after the event. The effect is quantitatively important: exposure to weather events leads to a 10-percentage points reduction in average forecast errors in the two months after the events (a 4% improvement in forecast accuracy).

I also found that there are differences across types of firms and analysts. I first compared firms classified as having high and low levels of physical climate risk (data sourced from Trucost) and found that forecasts from analysts who are exposed to weather events become more accurate for firms with high physical risks (e.g., after experiencing a hurricane, forecasts become more accurate for firms with high hurricane risks). This reduction in forecast error for high physical risk firms was particularly significant for more experienced analysts.

Taken together, my results support the information hypothesis as they show that exposure has an important effect in improving forecast accuracy for high-risk firms. However, they also show that not all analysts are able to extract the same information from exposure to climate events and that training inexperienced analysts could go a long way in improving climate risk assessment.

Figure 1: Change in forecast error before and after the weather shock

Call for action

Understanding how individuals and organisations perceive future climate-related physical risks is key to assessing the effects of climate change and implementing mitigation and adaptation policies. There is a need for enhanced climate risk disclosure from companies, and policy makers should mandate comprehensive reporting on both physical and transition risks.

The results of my research suggest that better disclosure should be accompanied with policy efforts aimed at incentivising training and education programs to ensure analysts correctly incorporate climate-related risks into their forecasts. Overall, proactive measures in these areas can enhance climate risk awareness and responsiveness within the financial industry.

This paper won the best PhD Student Paper at the Academic Network Conference in 2023.

It was presented at the 2023 Academic Network Conference at PRI in Person, Tokyo. Watch here.

The PRI’s academic blog aims to bring investors insights from the latest academic research on responsible investment. It is written by academic guest contributors. Blog authors write in their individual capacity – posts do not necessarily represent a PRI view.

References

Faralli, Matilde, What Drives Beliefs about Climate Risks? Evidence from Financial Analysts (January 19, 2024). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4700558

Mikhail, M. B., Walther, B. R. and Willis, R. H. (2007), ‘When security analysts talk, who listens?’, The Accounting Review 82(5), 1227–1253

NOAA (2016), ‘Storm prediction center wcm page’, Website URL: https://www.spc.noaa.gov/wcm