This chapter looks at how asset owners can be effective stewards of their assets and, if such functions are outsourced, determine how an investment manager deals with stewardship and active ownership issues.

The topic of active ownership is split into engagement and voting. Both activities have distinct characteristics that asset owners should be aware of in the selection process.

Engagement

Asset owners can engage with companies on three levels:

1) Direct engagement.

2) Collaborative engagement (may include asset owners and investment managers and is unlikely to be the sole method of engagement).

3) Outsourced engagement:

- a. carried out by an investment manager (who may sub-contract to service providers); or

- b. carried out by a specialist service provider (directly contracted by an asset owner).

Collaborative engagement

It is often the case that a single asset owner or manager represents a very small part of a company’s overall capital. A group of investors of the same standing therefore tends to have a higher chance of engaging successfully compared to one single voice. Collaborating with peers also facilitates the dissemination of best practices across the industry. Insight from peers can give asset owners confidence during the selection process to identify whether an investment manager is lagging or setting an example in engagement. Understanding collaborative engagement tools the investment manager may use, such as the PRI Collaborative Engagement Platform, can also aid the selection process.

Outsourced engagement

The process that an investment manager uses to engage, as well as its perceptions of engagement, should always be assessed. Does it see engagement as a fee-sapping evil or as a genuine opportunity to add value? It is also important to understand the semantics around engagement and voting, as some managers may promote pure voting activities as engagement. Engagement activities can directly impact financial performance. Equally, asset owners must understand a service provider’s intentions (whether that service provider is a manager or an engagement specialist mandated for the task) when they engage. An investment manager’s engagement should arguably always be instrumental to stronger investment performance, whereas a service provider’s (a pure engagement provider) engagement approach can reflect a wider set of drivers in asset owners’ strategy and policies.

If a purely instrumental view is held, an asset owner should measure the cost-benefit ratio of the engagement activity it is willing to support. It is important that asset owners explore what motivates them to engage and then ensure that that perspective is followed through. An asset owner may outsource engagement if a product does not offer an engagement overlay or share their motivations for engagement. It is also possible that a manager does not address engagement needs but provides investment products that incorporate ESG factors into investment decision making.

Asset owners should ask for examples of how a manager’s engagement approach is structured. Identifying the individuals responsible and understanding the processes involved is a good first step, with ascertaining how those individuals interact with investment decision makers a good second step. Examples of recent engagements and their outcomes are useful in assessing a manager’s engagement capability. It is also important to understand if engagements are initiated across all the manager’s assets. If the manager outsources engagement to a third party, asset owners should ask about the terms of the arrangement and the sustainability of it.

Beyond targeted engagements, asset owners should analyse the relationships a manager may have with the firms it invests in. It is rare (but possible) that routine analyst and portfolio manager dialogue already covers ESG issues and no further engagement is therefore required. Asset owners must be confident of staff ESG competency in such a case. It is also unlikely that principles-based issues are considered in engagements that are driven purely from a portfolio management perspective.

Active versus passive

Asset owners should have the same fundamental perspective on engagement regardless of whether an active or passive strategy is in question. Passive products are often chosen to limit the cost of managing assets and any engagement overlay may negate that. However, it could be argued that the stewardship role an asset owner assumes by investing on beneficiaries’ behalf has a cost implication – in the same way as does the management and administration of a fund. Therefore, engagement costs are part of running asset owner activities. This is particularly true when it comes to voting (discussed ahead). The old adage “if you can’t sell, you must care” to safeguard your investments further encourages long term passive asset holders to engage. They have a general interest to manage negative externalities (such as corruption or climate change) which could damage the economy or sector in question.

Meanwhile, passive investments are not necessarily blind. For example, factor investing can be considered as passive, although such investments do not follow a benchmark blindly – meaning all investment decisions are essentially active. With such strategies, engagement on specific ESG issues can and should be implemented, and the selection process should consider a manager’s approach to this.

Using service providers

When engaging through service providers, asset owners should ideally define topics to raise, as well as companies to target and objectives to achieve (this may be done via a policy or as a more hands-on, one-off exercise). Asset owners must reference topics and goals during the selection process and then monitor providers based on what has been agreed. Asset owners should be ready to participate in some of the engagements they care most about and establish in the selection and appointment process how such arrangements will work.

Asset owners must also make extra effort during the selection process to verify how portfolio managers and analysts responsible for making investment decisions receive the information collected through engagement activities.

Voting

There are often two starting points associated with voting:

1) An asset owner has its own voting policy in place and looks for an investment manager that can implement it via:

- a. segregated execution (shareholder rights remain with the asset owner);

- b. pooled execution (shareholder rights remain with the investment manager and it is rare for an asset owner to impose its voting policy on such funds).

2) An asset owner does not have a distinct voting policy and relies on an investment manager’s standard voting practices, regardless of the fund structure.

When selecting a manager, asset owners should ask about the voting process, including in terms of quality and suitability of execution, as well as any professional parties involved.

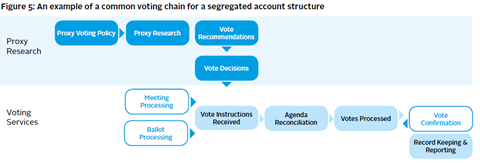

In the voting chain, a policy – from an owner or a manager – forms the basis for all voting under regular circumstances. Asset owners or managers then often appoint proxy service agencies to help them formulate voting recommendations for specific issues and/or companies based on the overarching policy. Actual voting decisions are then made based on the proxy research recommendations and other factors such as feedback from engagement activities. Future voting intentions, if ascertained in good time, may inform engagement activities ahead of any meeting.

For the actual AGM vote, voting decisions are passed into execution where another set of service providers are engaged to execute the vote and confirm that that vote reaches the ballot. The voting chain reverses and the results are reported to an asset owner and/or manager for further considerations, including commencement or ceasing of engagement activities and/or input into investment decision making, with the potential for divestment.

From a selection perspective, asset owners need to ensure the mechanistic aspects of the voting chain function properly, that quality service providers are obtained and votes reflect their target(s). Voting can become a technical and complex issue with potentially multiple jurisdictions involved. Asset owners must also ensure that all insight gained during the process is incorporated into future decision making across their assets.

Voting policy

Asset owners should have an investment policy in place that includes their active ownership perspective, with voting a key component. The PRI’s recent report, Investment Policy: Process & Practice - A Guide for Asset Owners, outlines how to formulate and review a policy. A clear policy makes any service provider or manager selection process easier – to a simple question of how well they can implement the policy. Focus will be on the processes described previously, effectiveness of voting (cost and impact) and responsiveness of the process. Asset owners must determine whether a manager has the capacity in-house and/or a quality third-party service provider retained.

In a situation where an owner’s voting policy is clear, the chosen investment product plays a key role. With segregated products, effecting an asset owner’s policy is a relatively straightforward task. With a pooled product, an asset owner should still endeavour to include its voting policy directions. An investment manager’s ability to adhere to potentially diverse instructions would then become a key differentiator in selection or an asset owner would need to find a pooled product where the manager’s voting policy aligns with its own policy. Groups of smaller asset owners can develop a customised voting policy and ask a manager to implement that policy for the percentage of holdings they collectively have in the fund. Flexibility for such activity would need to be addressed during the selection process.

If an asset owner is unclear about its own voting policy, or does not have a policy and is searching for an investment manager to vote on its behalf, the underlying manager voting policy needs to be examined. Any discrepancies between an owner’s views – in cases where an owner has no policy – and a manager’s policy need to identified. Any misalignments should manifest during the selection process and potential solutions should be discussed.

Voting process

On the basis that an asset owner has a clear view on what voting should achieve, the next stage is to find a manager with a robust voting execution process – from registering instructions to reporting on voting outcomes. An investment manager that cannot cast two different votes for separate funds would probably be unsuitable for an asset owner seeking to strictly implement its own guidelines. Securities that are not segregated cannot generally be voted on separately; the segregation process would be lengthy and might incur an additional fee. Dynamics like these need to be well understood and accounted for in the selection phase and weighted against an asset owner’s voting requirements.

An investment manager may have in-house voting capabilities or it may outsource to service providers. It is also important to understand how, or if it is possible, for an asset owner to potentially bring voting in-house or keep voting back altogether under special circumstances.

Voting outcomes

Beyond checks and balances on whether votes were registered and reached the ballot, evaluating voting outcomes should take place at the company and portfolio level. Voting against increasing the compensation of management that is failing to deliver is a standard example. An asset owner can question if a vote was successful in reducing the compensation, or preventing an increase, and how an unsuccessful vote changes future activity (such as a change in directors or blocking re-election of the compensation committee). An unfavourable outcome might lead to the portfolio weight of the stock being reduced. A higher allocation or assigning higher ESG ratings to more responsive companies is an alternative if a positive outcome is reached. The selection process should show how an investment manager can deliver basic outcome information to an asset owner as well as inform its own decision-making process and how voting impacts this.

Securities lending and derivatives

Some investment managers lend equity and bonds to boost portfolio returns by the margin earned from lending. If those securities are not recalled in time to exercise voting, the borrower is entitled to vote them. Negative publicity might result in controversial votes in stocks with concentrated ownership. Similarly, selecting a product that provides synthetic exposure to a stock or an index through a derivative might not come with voting rights. Buying into an ETF would typically mean no voting rights on the underlying securities. While these questions mostly affect and should be dealt with at the general investment policy level, the selection process can shed light on how investment managers can help to manage such issues.

Download the full report

-

Asset owner guide: Enhancing manager selection with ESG insight

March 2018

Asset owner guide: Enhancing manager selection with ESG insight

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

Currently reading

Assessing active ownership through engagement and voting

- 5

- 6