Cyber security in practice: Insights from the engagement dialogue

The dialogues showed that cyber security continues to be a sensitive issue for corporates to talk publicly about. Some are concerned that too much disclosure may draw undesired scrutiny from hackers, while others are at early stages in terms of building an understanding of the issue, and therefore are not prepared to put detailed information in the public domain. These concerns may explain why there are still gaps in cyber security-related disclosures.

Nonetheless, in contrast to their initially limited public reporting, companies contacted through this engagement were open to private dialogue and willingly made their experts – usually chief information security officers or digital directors (as well as staff from their sustainability and investor relations teams) – available to help investors develop a more comprehensive view of how they are addressing cyber security risks. The level of access and the depth of information provided was extremely valuable for investors, who typically found it challenging to ascertain companies’ positions from public disclosure alone.

The section below features key trends and investors’ learnings from the engagement dialogue over 2017-19. It also outlines good practice examples on the following four areas:

- Board oversight;

- Board expertise;

- Monitoring across the value chain; and

- Building capacity.

I. Board oversight background

To demonstrate that cyber security is an organisational priority, companies should establish board oversight of the issue. Boards have a role in ensuring that cyber security considerations are not just integrated into risk management, but that they also drive strategy and shape broader business decision making.11 To enable this, board members should receive quality management information and be wellinformed so that they can sense-check the adequacy of cyber security programmes, and challenge management actions where appropriate. This does not mean that the board should be involved in the day-to-day technical and operational issues. However, it must set expectations and have confidence that operational, financial and strategic resilience tied to cyber security is in line with those expectations.

Disclosure

Gauging from public disclosure among the companies engaged during this process, board oversight of cyber security issues was far more common in 2019 than in 2017. Most companies engaged had allocated responsibility for cyber security at the board level – often via the audit committee, risk committee or a sub-committee of the risk committee focused on IT resilience (Indicator 5). In some cases, cyber security had been prioritised to the extent that a separate board committee was set up to provide strategic guidance and governance. This was more common among companies with more advanced thinking on cyber security.

UK-based financial services company Standard Chartered disclosed that its financial crime risk board committee is composed of independent non-executive directors and external advisors with extensive experience in cyber security and international security; it said that the committee provides the company with “a valuable external perspective”.12

Several companies also indicated that their board or the board sub-committee received frequent updates, usually half yearly (if not quarterly) from the chief information and security officer (CISO), the chief information officer (CIO), or executive committees with cyber security-related responsibilities.

For instance, Australian financial group Suncorp Group, began to disclose in 2019 that its board is responsible for overseeing cyber security and that “cyber risks are reported at least quarterly through the Board’s Risk Committee.”13

However, companies lagged in their reporting of details of what information the board receives and how it is evaluated. While there were some improvements since 2017 (see example below), almost three-quarters of the engaged companies were yet to make progress on disclosure (Indicator 7).

Booking Holdings, a US-based engineering company, disclosed that its audit committee regularly reviews and discusses with management the company’s exposure to cyber risks. The audit committee reports to the board quarterly on this topic, “including impact on operations, business and reputation, the steps management has taken to monitor and mitigate such exposures; [and] significant legislative and regulatory developments that could materially impact the company’s privacy and data security risk exposure”.14

Engagement insights

Given overall inadequate public disclosure, investors were keen to understand through the engagement how boards exercise oversight of cyber security matters. They raised questions around the extent and quality of reporting to the board and how this is evaluated and challenged to steer cyber resilience across the organisation. They found that this level of information was critical to develop a view around the robustness of decision making on cyber security issues within the firm. Some of the key themes are discussed below.

Board reporting

Most companies revealed that, at a minimum, their boards received briefings from senior executives to educate them on cyber risk exposure. These briefings usually cover details of the threat environment, key industry incidents and how peers are addressing cyber risk. Some companies went further, contextualising these updates and informing the board of appropriate policies, cyber security risks and the probability of their occurrence, and cyber defence enhancements.

Companies that are leading on cyber security made it clear that their boards were well ahead in terms of assessing impacts on the business and agreeing on a level of risk tolerance. Cyber risk was incorporated into enterprise risk management systems, as opposed to being considered in isolation; as a result, regular risk reports were prepared by the CISO for the board. Furthermore, board members at these companies did not rely on one-way updates but actively participated in discussions with senior management on progress against expectations and improvement plans. For instance, one British retailer stated that there had been in-depth discussions between a non-executive director and the head of technology relating to the cyber security plans of one of its divisions.

Key performance indicators

A few companies indicated that they are looking to develop (or are in the process of developing) appropriate measures of cyber security performance for internal reporting. While a small selection of companies expressed reservations about sharing this information with the investor group, others provided granular detail. One US-based telecoms company said that it tracks metrics at different levels within the organisation (staff, management and executive) and reported to the board committee.

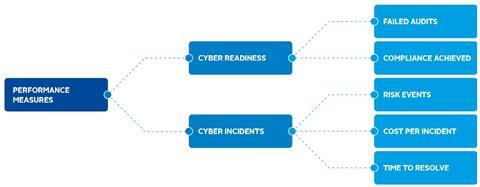

Overall, the performance measures and metrics that were highlighted in the dialogues can be grouped into two broad themes (see Figure 2):

- Cyber readiness, e.g. compliance scores, failed audits, data loss prevention and quantitative data on vulnerability management, security infrastructure and anti-malware; and

- Incidents, e.g. risk events, number of attacks, cost per incident, time to resolve etc.

Figure 2: Commonly identified measures of cyber security performance

Despite this level of communication, however, companies offered limited insight on how these metrics were selected or updated, and how they contributed to board evaluation of cyber security plans.

In a rare exception, a French financial institution provided investors with a deeper understanding of how metrics reported to the board add value to directors’ assessment of vulnerabilities and led to subsequent strengthening of cyber security plans. It explained that its board had received detailed scores on cybersecurity maturity for each of its subsidiaries following an independent analysis in line with information security standard ISO27001.15 This led to the company setting annual targets for cyber security improvements at each of its subsidiaries, which consequently led to improvements across the organisation.

Examples such as these highlight the role of board processes in relation to cyber security, in terms of evaluating current plans and driving strategic changes across the company. While investors may not have a pre-determined list of cyber security KPIs that companies should use, they certainly want board reporting to be useful, forward looking and actionable. Large volumes of retrospective cyber attack information are unlikely to promote informed decisionmaking within the company.16

II. Board expertise

Background

There has been some debate around whether board members should have cyber security expertise akin to qualified financial expertise. Some experts believe that, given the importance of technology in the modern economy and the prevalence of cyber risk, it is crucial that boards have specialist skills in this area. A recent MIT study found that companies with “digital savvy” boards tended to achieve greater revenue growth, return on assets, and growth in market capitalisation compared with their peers whose boards lacked such skills.17 Other experts think that cyber security is just one of many issues that boards need to evaluate, and therefore does not justify particular proficiency. They believe senior management is best placed to handle cyber security on a day-to-day basis, as long as the board is kept aware of the significance of the risks faced and how they are being managed.18

Disclosure

Over the course of the last two years, a growing number of companies in the engagement demonstrated that they were addressing board expertise on cyber security. Some companies reported that cyber security skills were explicitly considered when recruiting new board members (Indicator 10).

For example, Dutch financial company ING Group said that information technology is one of the areas of competence that is considered in the composition of its supervisory board, which is responsible for supervising and advising the executive board on cybersecurity risk.19

However, such details were provided by only 14 of the 53 companies engaged. Even among companies that had board members with relevant expertise, it wasn’t clear if such expertise was the decisive reason for appointing that member.

Engagement insights

Given that this was one of the least disclosed indicators, despite increased calls for cyber expertise on the board,20 investors were keen to understand companies’ perspectives on the issue.

In the engagement dialogues, most companies did not rule out the possibility of appointing directors with cyber security specific skills. However, they did not flag this as a priority criterion for board appointments. Companies said they were looking for a spectrum of relevant experience, and while cyber and IT skills are included in the mix, they could not be considered in isolation but in the context of existing and desired board composition.

The conversations also revealed that many companies were prioritising training to address deficits in board knowledge and expertise. For instance, a Dutch financial company told investors that it trained its management and supervisory boards twice a year, covering reports on the cyber-threat landscape i.e. what attacks look like and how they are evolving. Other companies indicated that they conduct board exercises to ensure their boards have the necessary guidance to respond to a major incident in terms of communication to the press, customers, regulators etc.

In addition to training, companies also look to external advisors to upskill their boards, facilitate strategic discussion and ensure that board members are able to ask the right questions and challenge senior management on cyber security. To this end, several companies said they had set up independent advisory panels and retained specialist consultants.

Overall, the engagement dialogues showed that companies have nuanced positions on board expertise on cyber and looked to training and external expertise where skill gaps were found – something that disclosure alone did not reveal.

III. Cyber security monitoring across the value chain

Background

Companies are increasingly reliant on the collection and processing of private data in their everyday business activities. Many use third parties and partners for these services. However, there are concerns that associates in the value chain, including suppliers and vendors, are weak links when it comes to a cyber security: they hold or have access to sensitive data but may not have appropriate policies and processes in place to adequately protect it. This creates pressure on companies to be proactive in setting high standards and identifying weak security measures in their value chains in a timely manner.

Disclosure

If disclosures are considered a reflection of cyber security practice, companies may not be doing enough. Even at the policy level, as of 2019 only 60% of engaged companies were yet to provide evidence of extension of their data protection and privacy policies to global operations and third parties (Indicator 3). This is concerning, because threats that may cripple external providers are likely to cause reputational and financial damage across the value chain.21

One company that did provide evidence of appropriate policies in this context was Novo Nordisk.

In its privacy policy, the Danish pharmaceutical company not only commits to be in compliance with personal data legislation, but states that it extends these standards to its value chain: “Although the legal obligations under European law apply only to personal information used and collected in Europe, Novo Nordisk will apply this Policy globally, and in all cases where Novo Nordisk processes personal information both manually and by automatic means, and whether the personal information relates to Novo Nordisk’s employees, contractors, business contacts or other third parties.22

Engagement insights

The engagement dialogues found that some companies were waking up to the potential risks around third-party practices. For instance, a financial company confirmed that it experienced nearly double the volume of attacks in 2017 compared to the previous year and many were attacks that targeted its suppliers. As a result, the company was increasingly focused on supplier vulnerability. A large retailer said that it ranked third-party risks among the highest cyber exposures it faces and had begun a monitoring process for sub-contractors on a case-by-case basis.

Some companies also stressed that value chain risk is often an industry-wide issue, so they were devising plans to address these risks with peers. For example, one bank indicated that it meets with other financial institutions every week to share intelligence on cyber security challenges.

However, generally speaking, companies’ efforts to address third-party risks appear to be piecemeal. A notable exception is a US-based medical device company, which has a sophisticated process for monitoring its value chain. It provided detailed information around monitoring of third parties, which includes systematic due diligence before signing contracts, ensuring secure boundary control for data, periodically reassessing partners’ cyber security performance and requiring them to share the results of regular penetration tests. It also stated that partners engaged for medical research were vetted via a security and privacy assessment and, when concerns emerged, they were required to undertake remediation or incorporate binding obligations in the contract.

Overall, the engagement showed that there is much more for investors to do to drive systematic policies and processes within companies on third party-related cyber security risks.

IV. Building capacity

A study of a representative sample of companies found that, on average, the annual cost of cyber crime per company reached US$13m in 2018, an increase of 72% over the previous five years.23 This raises questions around how companies are strengthening organisational capacity, including through recruitment and allocating appropriate budget to cyber security products, services and training staff. Staff training is an important element of risk management, as insiders often represent the weakest link in terms of cybersecurity.24

Disclosure

The answers to these questions are not always readily available in company reports. In fact, companies in the engagement raised concerns that such disclosure may attract unnecessary attention and testing by hackers. Nevertheless, the uneasiness to report may be declining, given the improvements in disclosure seen since our benchmark research in 2017 (with an increase from 19 to 31 companies reporting on Indicator 8).

An increasing number of companies have also started to disclose information around capacity building, detailing external expertise and collaboration (Indicator 9) with peers and national governments.

Some examples include:

Johnson & Johnson, a US-based healthcare company, which has an information security team which maintains “close working relationships with peer companies, industry associations and government agencies, both to share best practices and to collaborate on effective solutions to address the increasing threats and attack methods faced by both public- and private-sector organisations today”.25

AXA, a French insurance firm, which set up in 2015 a data privacy advisory panel, composed of experts in data privacy, including academics, members of think thanks and former members of regulatory bodies. The advisory committee meets twice a year in Paris.26

BT Group, a British telecommunications company, which launched in 2018 a free collaborative online platform to share information about malicious software and websites with its peers to help prevent cyber crime.27 This initiative is the result of collaboration with the National Cyber Security Centre – a UK government body that provides advice and support on computer security threats avoidance. BT believes that it is the first telecoms firm in the world to share this type of data with the industry.28

Engagement insights

During the engagement, investors sought to gain a better understanding of how corporate cyber security functions are resourced and equipped to defend against threats. Discussions found that companies had significantly increased their investments in this area in the last few years, increasing their capacity to deal with security issues and protect data. This is in line with industry research that suggests steep growth in corporate spending on cyber security products and services.29

The financial sector appears to be leading the way. For instance, one French financial firm quadrupled its cyber security spend over 2014-17 and increased the size of its team from 10 to hundreds over the period. This strategic shift was attributed to digitalisation, increasing criminality and terrorism, industry trends and internal assessments.

That said, companies are also strengthening capabilities and resilience through other ways – for instance, via the use of external service providers, providing training for staff, purchasing cyber security insurance, and collaborating with peers.

Companies indicated that they used external vendors and service providers to bring expertise to their teams and for testing and auditing purposes. At several companies, vendors conducted regular penetration tests to identify cyber vulnerabilities and work with internal specialists to remedy identified issues.

Some companies said that they were investing in their staff to mitigate risks. For instance, a British financial company indicated that it is making training more interactive through gamification – it said that 1,500 employees joined cyber games on a voluntary basis. The company is also working to build a culture of awareness by recruiting information security champions in every location. The champions are non-experts but are responsible for raising the importance and visibility of cyber risk.

Certain healthcare companies spoke about the use of cyber security insurance to minimise cyber security-related losses and secure business operations. They were of the view that insurance forms part of a comprehensive cyber security strategy, even though it does not prevent a cyber attack or fully compensate a company after one occurs. Other companies, however, expressed reservations: given rising premium costs and confusion about what cyber insurance does and does not cover, they preferred to self-insure through dedicated provisions.

Some companies indicated participation in collaborations coordinated by national governments to promote higher standards and drive better behaviours to handle threats that may not be as well understood. One example is run by the US Food & Drug Administration (see Box, The FDA’s Precertification Pilot).

The FDA’s precertification pilot program

Set up in July 2017 by the US Food & Drug Administration, an agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services responsible for protecting public health, the Software Precertification Pilot Program focuses on improving safety standards of software technologies in medical devices.30 Participants in the voluntary initiative include Apple, Fitbit, Johnson & Johnson, Pear Therapeutics, Phosphorus, Roche, Samsung, Tidepool and Verily.31 The pilot is still ongoing, and a summary of the FDA’s test activities was published in July 2019.

Another example is the Bank of England in the UK (see Box, Sector-wide simulations at the Bank of England) which has established a number of working groups to discuss sectorlevel challenges and consider third-party review processes.

Sector-wide simulations at the Bank of England

The Bank of England Security and Operations Centre has set up an initiative to evaluate the operational resilience of the banking sector. As a part of this, it is conducting an annual simulation to assess the ability of actors across the sector to respond to a cyber incident in the UK, identifying gaps and areas for future improvement.32 Participants include financial authorities, and representatives of the most systemically important firms.33

References

11 Marsh (2018), Governing Cyber Risk: A Guide for Company Boards

12 Standard Chartered, Annual Report 2018, p. 89

13 Suncorp, Corporate Governance Statement 2017-2018, p. 19

14 Booking Holdings (2018), Audit Committee Charter, p. 5

15 ISO27001 is an international standard for information security management systems, a framework of policies and procedures that includes all legal, physical and technical controls involved in an organisation’s information risk management processes. Its technical definition can be found here.

16 TheCityUK (2018), Governing cyber risk: a guide for company boards

17 It Pays to Have a Digitally Savvy Board, Peter Weil, Thomas Apel, Stephanie L. Woerner and Jennifer S. Banner, 12 March 2019, MIT Sloan Management Review

18 See, for example, Council of Institutional Investors (2016), Prioritizing Cybersecurity: Five Investor Questions for Portfolio Company Boards.

19 ING, Supervisory Board Charter and Profile, as of 31 December 2019

20 See, for example, Good Governance: Do Boards Need Cyber Security Experts?, Robin Ferracone, 9 July 2019, Forbes.

21 For examples of recent high-profile incidents, see Verizon (2019), Data Breach Investigations Report.

22 Novo Nordisk (2019), Data Protection Binding Corporate Rules Policy

23 Accenture (2019), The Cost of Cybercrime: Ninth Annual Cost of Cybercrime Study

24 See Accenture report above for examples.

25 Johnson & Johnson, Health for Humanity Report 2018, p. 103

26 AXA, Data Privacy Advisory Panel webpage.

27 BT, Digital Impact and Sustainability Report 2018/19, p. 17

28 NCSC, What we do webpage.

29Gartner Forecasts Worldwide Information Security Spending to Exceed $124 Billion in 2019, 15 August 2018, Gartner press release.

30 Food & Drug Administration, Precertification (Pre-Cert) Pilot Program: Milestones and Next Steps, as of 18 July 2019.

31 Food & Drug Administration, FDA Selects Participants for New Digital Health Software Pre-certification Pilot Program, as of 26 September 2017.

32 Bank of England, Sector Simulation Exercise: SIMEX 2018 Report, as of 27 September 2019.

33 Bank of England, Bank of England sector resilience exercise, as of 27 September 2019.