This introductory guide explains what screening is and why investors apply screening rules.

Overview

- The guide outlines key steps for implementing screens based on environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors.

- It explains how screening relates to other responsible investment practices, such as ESG integration and stewardship.

- For more information on screening, or responsible investment more broadly, email [email protected].

The guide is split into three sections:

Note on the Pathways framework

It is clear from recent PRI signatory consultations that a growing number of signatories wish to advance their responsible investment practices in more relevant ways. In response we are developing Pathways, a framework that acknowledges the varied contexts in which signatories operate and allows them to differentiate their activities based on their duties and objectives. For more on this, please refer to the section of the guide on understanding how investor intent can influence screening practices.

What is screening?

Screening is the application of rules based on defined criteria that determine whether investments are permitted in a portfolio. Screening criteria can be based on various investment characteristics, including ESG factors.

As a responsible investment practice, screening can be categorised in the following ways:

|

Exclusionary screening / exclusions |

Negative screening |

Positive screening |

Best-in-class screening |

Norms-based screening |

|

Applying rules based on… |

Applying rules based on… |

Applying rules based on… |

Applying rules based on… |

Applying rules based on… |

|

ESG criteria… |

‘undesirable’ ESG criteria… |

‘desirable’ ESG criteria… |

ESG criteria that are ‘desirable’ relative to peers… |

compliance with widely recognised ESG standards or norms… |

|

that determine whether an investment… |

that determine whether an investment… |

that determine whether an investment… |

that determine whether an investment… |

that determine whether an investment… |

|

is not permitted |

is not permitted |

is permitted |

is permitted |

is or is not permitted |

Examples of ESG standards and frameworks used in norms-based screening include:

- The UN Global Compact

- The Paris Climate Agreement

- OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises

- The International Bill of Human Rights

- World Governance Indicators

Screening rules can be applied across different asset classes and investment styles. There are variations in the ways screens are designed and implemented depending on the asset type they apply to.

| For publicly traded liquid assets (listed equities, bonds, etc.) |

|

| For privately traded illiquid assets (real assets, private equity, etc.) |

|

Screening often sets the initial boundaries for investment selection. It can complement other RI approaches, such as ESG integration and stewardship, but is distinct from them. The PRI, CFA and Global Sustainable Investment Alliance have collaborated to align definitions of each of these approaches and explain how they are used.

Screening investments based on ESG criteria goes back at least a century.1 Screening can be traced to faith-based approaches that avoided companies which were involved in activities seen as incompatible with a set of beliefs or values. From the 1960s, screening out industries like tobacco became more widespread,2 and screening rules have since expanded to cover a broad range of criteria, such as female representation on boards.

Screening remains one of the most widely used RI practices. Around US$3.8 trillion in assets are subject to negative / exclusionary screens, US$1.8trn to norms-based screens and US$574 billion to positive / best-in-class screens.3

PRI resources

- Technical guide | ESG integration in listed equity (2023)

- Introductory guide to responsible investment: stewardship (2021)

Why use screening?

Screening is undertaken by investors with a range of different objectives, including those outlined in figure one below.

Screening is not a requirement of responsible investment. However, it is considered good practice for PRI signatories to consider whether using screens based on ESG and sustainability factors would help them achieve their financial return and / or sustainability objectives in line with their fiduciary duties.4

Figure 1: Reasons for applying screening rules

Financial materiality

Investors can apply screens to optimise risk-adjusted financial returns. An investor may use a screening process to construct a portfolio of companies or assets that have a certain set of ESG characteristics which the investor believes contribute to under or outperformance.

A significant number of investors have set targets for their investment portfolios to emit net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 or sooner to protect portfolio returns as the world transitions to a low-carbon economy. Negative screening of assets is one lever investors can use to achieve their net-zero goals. In this case study, the German insurance and financial services group Allianz explains how it uses exclusionary screening as one element of its decarbonisation strategy.

Clients’ / beneficiaries’ ethical and sustainability preferences

Screening can be used to ensure investment portfolios reflect the ethical beliefs of end investors. For example, faith-based investors can exclude companies involved in sectors that go against their religious values, such as gambling or alcohol production.

Weapons screens are among the most widely used ethical screens.5 Views on the ethics of weapons are mixed and complicated. Some investors exclude all investments connected with armaments, while others consider financing the defence sector responsible and necessary so do not apply any screens beyond what is legally required. For investors that apply screens on weapons, a relatively widespread approach is to screen out controversial weapons, while allowing investment in other categories of armaments.

Applying screens also allows portfolio managers to align fund holdings with end investors’ sustainability preferences. Some investment strategies screen out activities such as thermal coal extraction for this reason.

There is mixed evidence on whether screening is an effective means of aligning portfolios with investors’ sustainability preferences. On the issue of climate change, one group of researchers found that investor divestment does result in real-world carbon emissions reductions,6 while another found that diverting capital from carbon-intensive firms can make them less likely to decarbonise.7 In view of the complexities, investors should carefully consider whether screening is an effective means of aligning with sustainability preferences.

Regulation

In some jurisdictions, financial regulations prohibit investment in certain assets or companies engaged in certain activities, such as manufacturing controversial weapons.

There are also regulated investment products that have screening requirements , for example, those that follow EU Paris-aligned benchmarks. These products are designed for investors looking to adopt low-carbon investment strategies that align with the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement. Providers of funds that track EU Paris-aligned benchmarks are required to screen out investment securities that meet specified criteria.

Understanding how investor intent can influence screening practices

A single screening rule can have multiple objectives, and investors can implement multiple screening rules within an investment strategy.

The table below sets out how investors with different intents may approach the question of screening tobacco.

Figure 2: How investor intent can influence screening practices

| Incorporating ESG factors | |

| Investors aiming to achieve competitive risk-adjusted financial returns by incorporating financially material ESG-related risks and opportunities into investment and stewardship decisions… | May conclude that investments in tobacco producers can be profitable and so do not screen out this economic activity. |

| Addressing drivers of systemic risks | |

| Investors aiming to achieve competitive risk-adjusted financial returns by incorporating financially material ESG-related risks and opportunities and taking action to address drivers of financially material sustainability related systemic risks… | May conclude that while investments in individual tobacco producing companies can be profitable, the negative health effects caused by tobacco do significant harm to health systems, thus to the economic system and market overall, undermining the investor’s financial objectives. Therefore, they screen out this economic activity. |

| Pursuing sustainability impact | |

| Investors aiming to achieve a positive contribution to sustainability goals while meeting financial returns objectives by incorporating financially material ESG risks and opportunities and pursuing positive contribution(s) related to specific sustainability issues… | May conclude that while investments in individual tobacco producing companies can be profitable, the negative health effects cause significant harm to people and thus undermine the investor’s sustainability goals. Therefore, they screen out this economic activity. |

Investors need to be clear on the intent behind screens. Clear objectives underpin coherent and effective investment strategies. This clarity also allows for precise communication with end-investors, fostering trust and confidence.

PRI and external resources

- Academic research | The effectiveness of divestment strategies (2023)

- Thought leadership | Discussing divestment: Developing an approach when pursuing sustainability outcomes in listed equities (2022)

- Academic research | Exit versus Voice (2022)

- Thought leadership | Understanding and aligning with beneficiaries’ sustainability preferences (2021)

How to apply screens

Below are key steps investors can take when using screening as a responsible investment approach.

Figure 3: An RI screening process

Identify objectives

Investors should identify whether it is necessary and effective to introduce any organisation-wide investment screening rules and be clear on the rationale. Investors should also decide whether additional screening rules are needed for specific investment strategies.

Objectives can be based on an investment organisation’s in-house views and / or requirements from clients / end investors and should meet regulatory requirements. It is good practice for voluntary screening to align with international standards, such as the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises or the International Bill of Human Rights.

Communicate clearly

It is important that screening rules are presented clearly. Screening rules should cover:

- the criteria evaluated (e.g., involvement in a certain economic activity, such as coal extraction);

- the thresholds against which the criteria are assessed (e.g., percentage of total revenue);

- the methodology for applying the screens (giving relevant information about data sources and clarifying definitions where relevant); and

- the rationale for the screens.

Asset owners should include details on the screens they require in RFPs and investment management agreements.

Investment managers offering pooled funds that apply screens should provide details on the screening rules in prospectuses and other marketing documents.

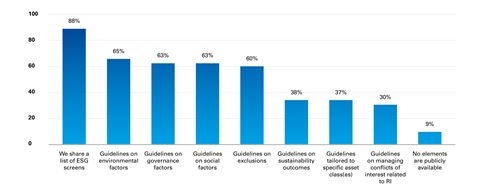

It is recommended that organisations set out their high-level position on screening, including exclusions in their publicly available RI policies. In 2023, around 60% of PRI investor signatories had publicly available guidelines on exclusions.

Figure 4: Signatories’ publicly available RI policy elements

Source: indicator PGS 3 (2023). Denominator: 2,859

Examples of PRI signatories’ high-level screening guidelines

|

Eiffel Investment Group, France, investment manager, AUM US$1 - 9.99bn. See: Exclusion policy. |

“Eiffel has decided to exclude companies involved in the exploration, drilling, extraction, production, transportation and storage of (conventional and unconventional) oil and unconventional gas. Eiffel also undertakes to exclude any financing of new projects and / or exploitation of new oil or gas reserves.” |

|

Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company, Japan,AUM US$250bn+. See: Guidelines on the Promotion of Responsible Investment. |

“We prohibit investment and financing for companies that manufacture weapons (such as cluster bombs, anti-personnel landmines, and […] weapons such as biological and chemical weapons) that could seriously harm the general public.” |

|

Stonepeak Infrastructure Partners, investment manager, United States, AUM US$50 - 249.99bn. See: RI policy. |

“The scope of Stonepeak’s investment activities is governed principally by provisions within limited partner, investment advisory, and investor side letter agreements […] while Stonepeak does not maintain an explicit exclusions policy, it is prohibited from investing in industries beyond the scopes of its various Agreements.” |

|

Transport for London Pension Fund, United Kingdom, AUM US$10 - 49.99bn. See: Statement of Investment Principles - 2023.

|

“The Trustees, in partnership with like-minded pension schemes, aim to use engagement as a way to encourage companies to adopt sustainable business models and practices. However, where “sufficient” progress has not been made or is not forthcoming in view of the Fund’s managers, the Trustee is open to the consideration of divestment and exclusions.” |

Assign oversight

Strong governance helps ensure screens are correctly implemented. It is good practice for organisations to formally assign senior-level accountability for screening. The function or group responsible generally monitors the appropriateness of the criteria / thresholds in the screening rules and their proper implementation.

Integrate into the investment process

The information used to implement screening rules needs to be sourced and integrated into portfolio management systems. Some investors screen for involvement in ESG incidents/ controversies which requires frequent close monitoring of information on investees.

Implementing screens can be complex. Companies often have multiple subsidiaries, necessitating careful attention to ensure that all relevant entities are covered by screening rules.

Monitor and review

It is constructive for investors to present the implications of screens to clients and beneficiaries. Factors or metrics to monitor and discuss can include:

Tracking error

- Screening reduces the investable universe, thereby potentially raising a portfolio’s tracking error against a benchmark.

Style factors

- Screens may underweight or overweight sector exposures within a portfolio. This may introduce a style bias, portfolio ‘tilts’, or different foreign exchange exposures. Other screens may introduce bias to larger capitalised companies or styles (e.g., growth over value).

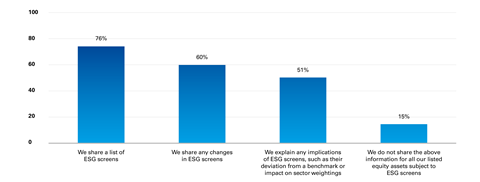

2023 PRI reporting data shows that most listed equity investor signatories are disclosing relevant details about their screening processes, if they employ them (see below).

Figure 5: Disclosure of ESG screens by listed equity signatories

Source: indicator LE 12 (2023). Denominator: 846

Investors should monitor their screening rules on an ongoing basis i.e., collect data from different sources to verify that the information being used to execute screens is correct. For example, if one data provider reports that a company generates 20% of its revenues from gambling and another reports the same company generates no revenue from this activity, it could mean a screening rule is not being executed correctly.

It is good practice for investors to review screening rules periodically to assess whether the criteria targeted remain appropriate and thresholds are set at an effective level.

PRI resource

Webinar recording | Putting responsible investment screening into practice (2024)

Downloads

An introduction to responsible investing: screening and exclusions

PDF, Size 0.89 mb

References

1 Morgan Stanley (2016), Catholic Values Investing, p2

2 MSCI (2024), The Evolution of ESG Investing

3 Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (2022), Global Sustainable Investment Review, p13

4 PRI Reporting Framework (2024). Indicators PGS 1, 3

5 Fernando Luque (2023), How to Exclude Weapons from your Portfolio

6 Martin Rohleder et al (2022),The Effects of Mutual Fund Decarbonization on Stock Prices and Carbon Emissions

7 Samuel Hartzmark and Kelly Shue (2022), Counterproductive Sustainable Investing: The Impact Elasticity of Brown and Green Firms