Significant new infrastructure investment is fundamental to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), but the sector remains underfunded compared to global sustainable development and economic growth needs.

Nonetheless, there has been growing attention on what can be defined as ‘sustainable infrastructure’ – infrastructure assets and systems that may achieve positive real-world outcomes.

As this paper will outline, many infrastructure investors are already considering the SDGs in their investment approaches for various reasons:

- government action

- LP pressure

- attention from beneficiaries and the general public

- to win new business

- employees’ personal convictions

Nonetheless, practice is far from consistent. More standardised approaches are needed to help all stakeholders – whether LPs, GPs, civil society or governments – understand how and which infrastructure investments shape outcomes in line with the SDGs, and how common interests can be aligned most effectively. Only then will the potential of infrastructure investment in relation to the SDGs be realised.

Common approaches

Investors are taking various approaches to identify SDG outcomes, define targets and policies in relation to the SDGs, and shape SDG outcomes through their investment decisions and asset management.

These focus predominantly on existing investments, typically taking into account the services provided by different infrastructure assets, or the way they are managed, to achieve certain outcomes, or a combination of the two.

Often, these assessments are risk-based, determining the impact of the world on a portfolio or asset. To consider SDG outcomes, the impact of a portfolio or asset on the world must be taken into account instead.

There is no single approach to identifying what type of infrastructure assets are likely to have certain outcomes in line with the SDGs. An asset’s context – its geography, relations with local communities, type of services provided, its wider supply chain, and so on – is critical to identifying its different outcomes.

Although approaches require greater consistency, different investors, whether asset owners or investment managers, are beginning to use the SDGs to set targets for elements of asset management or for overall strategy or portfolio construction.

Similarly, some governments are using the SDGs to help shape their infrastructure planning and project design requirements. This should encourage investors to align their own internal processes to position themselves better in government tenders for new infrastructure projects.

Infrastructure investors are communicating their work in relation to the SDGs on a more regular basis, and several tools and service providers are developing metrics and analysis to support these efforts. It is also clear that metrics need to be developed further and with that, more clarity on how infrastructure investors are genuinely seeking to shape outcomes.

Challenges

Although infrastructure investors are integrating the SDGs into their investment processes, significant challenges must be overcome for this to become widespread, meaningful and consistent. These include:

- data gathering

- aligning SDG outcomes and financial considerations

- setting consistent outcome objectives along the investment chain

- greater government-investor engagement

- developing internal and external skillsets

- allocating more capital to greenfield as opposed to brownfield investments

- enhanced investor collaboration

Next steps

The progress made so far by infrastructure investors in investing with SDG outcomes, and the very real gaps that still exist within practices in the sector, need to be addressed if the potential for infrastructure investment to contribute to the SDGs is to be fulfilled.

There are several high-level areas of action that infrastructure investors and other industry participants – such as governments, developers and consultants – can take.

Table 1: Areas of action for infrastructure investors and industry participants

| Challenge | Example actions |

|---|---|

| Data gathering | Investors and service providers work together to continue to develop tools and incentives. |

| Aligning SDG outcomes and financial considerations | Explore ways in which consideration of sustainability outcomes can be built into different stages of the investment process. |

| Setting consistent outcome objectives | Closer coordination between asset owners and investment managers on defining SDG outcome objectives. |

| Government-investor engagement | Enhance existing dialogue with governments on infrastructure pipelines and project design to place a stronger focus on sustainability factors. |

| Skillsets | Internal training and hiring policies reflect need for enhanced ESG skillsets – where these are unavailable, external partnerships are explored. |

| Greenfield vs brownfield investing | Consider strategic asset allocation decisions to allow more greenfield investment, where outcomes can be more often embedded from the outset. |

| Investor collaboration | Join or continue to support industry initiatives (including those developed by the PRI) to foster greater collaboration between investors. |

Read the full report

About this paper

This discussion paper details the current approaches that infrastructure investors are adopting to consider the Sustainable Development Goals as part of their investment approaches.

It highlights a range of challenges that such investors still face in seeking to shape real-world outcomes in line with the SDGs and suggests the steps they should take to address these and deepen their integration of the SDGs. It builds on and complements the PRI’s existing work on the importance of the SDGs and investors’ role in contributing to them:

- ‘The SDG investment case’ , which laid out why the SDGs are relevant to institutional investors, why there is an expectation that investors will contribute and why investors should want to.

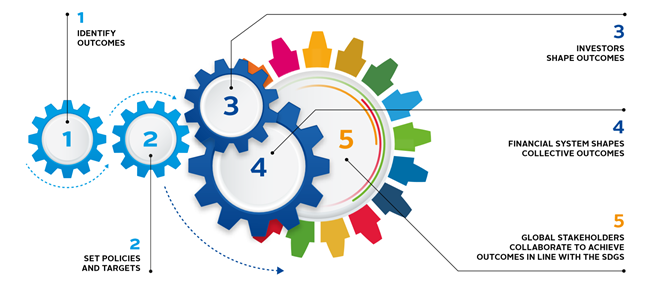

- ‘Investing with SDG Outcomes: a five-part framework’ , which explains how institutional investors might seek to understand the real-world outcomes of their investments, and to shape those outcomes in line with the SDGs.

To support meeting the SDGs, investors must understand the positive and negative outcomes from their investments – as well as how they can shape those outcomes. A focus on shaping SDG outcomes involves broadening the approach from being an analysis of financially material ESG issues at an individual investee level, to also include a parallel analysis of the most important outcomes to society and the environment at a systems level.

PRI: Investing with SDG outcomes: a five-part framework

The paper is not intended to provide specific technical guidance for infrastructure investors. Nonetheless, by conducting a detailed review of how infrastructure investors are approaching the SDGs, it aims to:

- build knowledge of the SDGs and their relevance for infrastructure investors;

- explore different ways that investors in the sector can build consideration of SDG outcomes into their investment processes;

- support ongoing discussions within the sector and its different stakeholders on how to move best practice forward in a manner that reflects the urgency of achieving the SDGs by 2030.

This is not targeted at specific segments of the infrastructure investment community or investors based in or investing in different geographies. The issues and approaches highlighted are intended to help all types of infrastructure investors as they consider their work in relation to the SDGs. Moreover, although focused on the infrastructure asset class, we anticipate that many of the key discussion points will also support work by investors in other asset classes, particularly real assets and private markets more broadly.

With the help of consultant AECOM, this paper has been developed following an extensive research process encompassing:

- a series of roundtables and events1 in Melbourne, New York, London, Paris and Mexico City, with the participation of over 100 infrastructure practitioners, including investors, government, industry associations, engineering firms, and service providers;

- interviews with selected infrastructure investors (both asset owners and investment managers);

- a review of open-source materials on infrastructure and the SDGs.

- members of our Infrastructure Advisory Committee provided feedback throughout the development of the paper.

Market overview

This section covers:

- the importance of large-scale infrastructure investment to the achievement of the SDGs, and the current spending gap in this regard;

- the ways in which the SDGs and general sustainability factors are being adopted by governments and infrastructure investors alike.

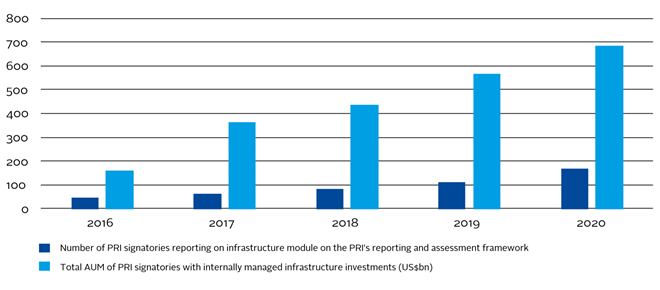

In 2020, the PRI’s signatories internally managed close to US$700bn in infrastructure assets. Market shocks notwithstanding, that figure is set to increase, given the record fundraising for infrastructure funds in 2019 2 , and so will the scope for infrastructure investing to support the achievement the SDGs by 2030.

Figure 1: PRI signatories investing in infrastructure

Massive new infrastructure investment is fundamental to the achievement of the SDGs. As a paper by the Economist Intelligence Unit highlights: “From transport systems to power-generation facilities and water and sanitation networks, [infrastructure] provides the services that enable society to function and economies to thrive… Encompassing everything from health and education for all to access to energy, clean water and sanitation, most of the SDGs imply improvements in infrastructure.”

However, the sector remains underfunded compared to sustainable development and projected growth needs. Even before the Covid-19 crisis, with its potential longterm economic and health repercussions, the OECD had estimated that global infrastructure investment of up to US$6.9trn is required annually until 2030 to meet climate and broader development objectives.

At the same time, there has been growing attention on what can be defined as ‘sustainable infrastructure’ – infrastructure assets and systems that may achieve positive real-world outcomes. The Inter-American Development Bank , for example, has defined sustainable infrastructure as “infrastructure projects that are planned, designed, constructed, operated, and decommissioned in a manner to ensure economic and financial, social, environmental (including climate resilience), and institutional sustainability over [their] entire life.” The organisation claims that this framework supports progress towards nearly 75% of the SDGs’ 169 targets.

This combination of infrastructure investment need and sustainability factors is starting to filter into national government infrastructure strategies and planning, and Covid-19, by exposing weakness in public health and social care systems, should intensify this process. While not explicitly referencing the SDGs, countries as diverse as the UK, Canada and Malaysia, are seeking to integrate sustainability factors – notably climate change-related issues – into their long-term infrastructure and development plans.3 The European Union’s Green New Deal , a proposed investment and growth programme for the bloc as it aims to become carbon-neutral by 2050, also makes clear the need to align climate-related investments with a range of SDGs.

As this paper will outline, many infrastructure investors are already considering the SDGs in their investment approaches, whether through thematic funds or more generally. This is happening for various reasons: government action; pressure from LPs, beneficiaries and the public at large; as a differentiator to win new business; personal convictions by individual managers or organisations’ leadership; and so on.

Nonetheless, practice is far from consistent. Infrastructure investors differ in the ways that they consider SDGs in their assets and portfolios; how they set targets and policies to decrease negative outcomes and increase positive outcomes in line with the SDGs; and how they monitor and achieve progress against those objectives.

More standardised approaches are needed to help all stakeholders, whether LPs, GPs, civil society or governments, understand how and which infrastructure investments shape outcomes in line with the SDGs, and how common interests can be aligned most effectively. Only then will the potential of infrastructure investment in relation to the SDGs be realised.

“From transport systems to powergeneration facilities and water and sanitation networks, [infrastructure] provides the services that enable society to function and economies to thrive… Encompassing everything from health and education for all to access to energy, clean water and sanitation, most of the SDGs imply improvements in infrastructure.”

The Economist Intelligence Unit

Common approaches

This section summarises the common ways in which infrastructure investors are considering the SDGs in their investment approaches. This includes:

- how SDG outcomes are identified;

- examples of how targets and policies in relation to the SDGs are being defined;

- how investors are shaping SDG outcomes through their investment decisions and asset management.

The discussion points highlighted below are structured around parts 1, 2 and 3 of the proposed framework defined by the PRI in its Investing with SDG Outcomes report, focusing on the steps that institutional investors are taking in relation to the SDGs.

There are also examples of collective action (parts 4 and 5 of the SDG outcomes framework), but these are addressed more directly in the ’Challenges’ and ’Next Steps’ sections of the report.

Figure 2: SDG outcomes framework for investors

1. Identify outcomes

Overview

The Investing with SDG Outcomes report highlights that investors can seek to identify outcomes caused by, contributed to, or linked to their investments.

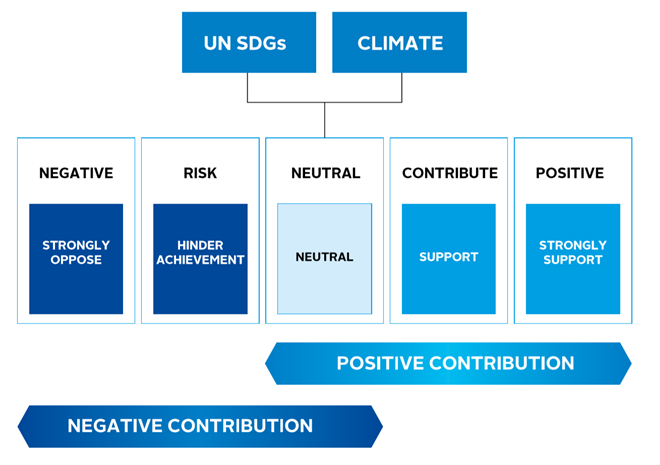

Our research suggests that, up to now, most infrastructure investors have done this by mapping their existing investments to the SDGs. This work has generally focused on positive outcomes. Where negative outcomes have been assessed, this has typically been done through an ESG risk assessment, and often only after a project has been designed and planning consent has been achieved. This means that certain outcomes, positive or negative, are already effectively embedded in the project and therefore more difficult for investors to shape.

There is also a further significant difference that needs to be considered through this assessment process: a risk assessment determines the impact of the world on a portfolio or asset, whereas considering outcomes should determine the impact of a portfolio or asset on the world.

This difference is explored in more detail in an example highlighted in Investing with SDG outcomes: A five-part framework , which considers the different ways in which an investor may assess the risks and potential outcomes associated with an investment in a beverage company in a water-stressed country.

This case highlights how having good ESG risk management, through strong governance systems and adequate permitting, may still lead to negative outcomes such as increased water stress – and potentially weaker long-term operational and financial performance. In contrast, in an approach that also focuses on shaping real-world outcomes of the investment, this outcome of water stress would be assessed before making an investment decision and then managed and monitored during the investment. In this case, understanding a specific SDG-related outcome would not only contribute to SDG 6 on Clean Water and Sanitation, but gives an early warning signal for a potential investment risk.

Connecting infrastructure with the SDGs

The roundtables and other research highlighted that infrastructure investors are considering different factors when identifying the outcomes of their investments:

- how infrastructure assets shape outcomes in line with the SDGs based on the services they provide;

- how those assets are actively managed to deliver targeted outcomes (which may include specific impact investment approaches);

- or a combination of the two.

The first approach presupposes that certain types of assets have inherent outcomes: for example, renewable energy assets could have positive outcomes in relation to SDG 13 on Climate Action or SDG 7 on Affordable and Clean Energy. The second approach supports the view that better outcomes can be achieved by more active management of assets, building on strong ESG processes.

Approaches vary between mapping investments to the SDGs at a goal level or attempting to go deeper and look more closely at the individual targets and indicators 4 . In most cases, this has involved building on existing ESG integration processes – such as conducting ESG materiality assessments – rather than designing specific new methodologies to assess SDG outcomes. Others have used ESG service providers such as Sustainalytics and Trucost to help with this process.

There is, therefore, no single or standard approach to identifying what type of infrastructure assets are likely to have certain outcomes in line with the SDGs. However, the research and tools cited in Figure 3 have been highlighted as guides for exploring connections between infrastructure and the SDGs.

Figure 3: Key research on SDGs and infrastructure

Selected research aims to identify the links between different types of infrastructure and the SDGs. For example:

- Infrastructure for sustainable development : This paper from organisations such as Oxford University, the United Nations Office for Project Services, the World Bank and the UK’s Department for International Development suggests that infrastructure influences all 17 SDGs, and over 120 of the 169 targets.

- The Relationship between Investor Materiality and the Sustainable Development Goals : The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board mapped 30 ESG issues to each SDG to assess their materiality. It also looks at the issues on a sector basis, including some types of infrastructure.

- The real assets ESG benchmark provider GRESB has mapped its Infrastructure Asset Assessment to the SDG targets and indicators to show how various infrastructure assets may contribute positively or negatively.

As infrastructure investors have gained more experience understanding their SDG-related outcomes, they have been able to expand their analysis. For example, some infrastructure practitioners have begun to explore the linkages between different SDGs, including the interdependence of ESG issues, rather than looking at each goal in isolation. Others have found that the more they assess project outcomes, the more they have found commonalities with the outcomes of similar infrastructure assets.

This has enabled organisations to finetune how they use the SDGs – whether in setting more focused targets at the outset of an investment or project, or considering how particular goals can be built into the design and construction of projects more effectively. This is covered in more detail in the next section of the report.

Mott Macdonald: Considering impacts

This engineering consultant identified a set of outcomes 5 as part of its bid for a UK sustainable transport project, recognising that achieving these was based on a series of interdependencies:

- Direct: SDG 11 on Sustainable Cities and Communities - developing travel infrastructure improved accessibility and affordability for vulnerable or excluded communities.

- Indirect: SDG 10 on Reduced Inequalities - increasing travel options gave the local population greater access to economic and social opportunities.

- Induced: SDG 16 on Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions - by addressing the above, the project aimed to reduce anti-social behaviour, and strengthen economic and educational opportunities.

Identifying positive and negative outcomes

The context around an asset is also critical for identifying and assessing current and potential positive and negative SDG outcomes. As an example, airports were cited frequently at our roundtables.

| Negative outcomes: | Positive outcomes: |

|---|---|

|

|

This needs to applied to any type of infrastructure asset: even renewable energy assets , which are commonly regarded as a strong ‘impact’ investment, require an understanding of local community, health and safety or supply chain impacts, among other factors, to properly assess positive and negative outcomes.

2. Set policies and targets

Overview

As stated in Investing with SDG outcomes: A five-part framework , “setting policies and targets… [moves] the investor from identifying and understanding unintended outcomes towards taking intentional steps to shape outcomes.” This is about building an overarching framework within an organisation to ensure that shaping outcomes in line with the SDGs is integrated into the investment process.

Investment policies

Many infrastructure investors already have a strong commitment to responsible investment. Infrastructure investors reporting to the PRI in 2019 received a median score of A (where E is the lowest score, and A+ the highest). Relatively few, however, formally embed strategies for shaping outcomes in line with the SDGs within their responsible investment policies. As highlighted by roundtable participants and through our broader research, there are several reasons for this:

- Investing in line with the SDGs remains a relatively new concept, with limited understanding among many investors.

- The SDGs are seen as an extension, or product, of existing ESG processes, and so formal changes to such policies may not be considered necessary.

- Shaping outcomes in line with the SDGs is considered an ‘impact’ investment and therefore may only cover a small proportion of funds or assets under management, rather than underlying all investments.

- A lack of formal demand from asset owners to investment managers to include them in policies.

- A recognition that developing an investment thesis in relation to the SDGs can be challenging, particularly in terms of measurable outcomes.

However, the SDGs can underlie an organisation’s responsible investment approach, even without being explicitly referenced in a responsible investment policy. Many infrastructure investors’ policies seek to reduce negative outcomes through objectives such as avoiding investment in companies or projects that cause significant environmental or social harm or aim to increase positive outcomes by supporting the transition to a low-carbon economy.

STOA: Working towards the SDGS

French energy infrastructure investor STOA’s responsible investment policy starts by stating: “STOA is a committed investor seeking to reconcile value creation and sustainable development. Our projects contribute to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the United Nations.” The policy highlights ways in which this might be achieved. For example, 30% of its investments are targeted for “climate-friendly” projects, while the organisation will not invest in projects which have “too high an environmental or social impact”, with a focus on issues such as biodiversity and the displacement of local populations.

Manager selection process

Asset owners’ infrastructure manager selection processes typically do not yet consider the SDGs in detail. This does not reflect a lack of interest among LPs in the SDGs: LPs that the PRI consulted during our research made clear that the SDGs are increasingly relevant, whether for commercial or reputational reasons. Instead, the lack of formal mandates in relation to the SDGs partly reflects the difficulty of developing a portfolio or fund-level view of the scope and scale of contributing to the SDGs, given the challenges in gathering data and comparing it meaningfully across a range of assets (see ’Challenges’). In addition, it highlights that many LPs have not yet defined their own commitments to specific SDG outcomes, as noted above.

Market developments – whether government-led or investor-driven – suggest that the role of the SDGs in manager selection processes will grow. For example, the recovery from the Covid-19 crisis may see governments prioritise social or environmental outcomes in infrastructure spending as much as financial considerations, influencing how investors participate in resulting projects and requiring closer alignment of interests between all players in the infrastructure investment chain.

Some infrastructure managers have already incorporated the SDGs into their investor and public communications 6 . Informally, asset owners also suggest that they are likely to look more favourably on infrastructure managers that can demonstrate greater potential for or commitment to certain SDG outcomes, assuming other elements of their offering are comparable with their competitors’.

Nonetheless, there is recognition by managers and asset owners that more rigour is required to drive consistent approaches to shaping SDG outcomes and communications to avoid claims of ‘SDG-washing’, for example.

Portfolio building

Infrastructure investors agree they can consider how different assets might shape SDG outcomes during portfolio construction and subsequently, when analysing potential transactions. Nonetheless, there is recognition in the industry that there needs to be greater consistency on how such SDG considerations should be applied.

- Roundtable participants typically agreed that potentially ‘better’ performing assets or sectors from an SDGs perspective should be rewarded by greater flows of capital, at the expense of assets that have more potential to cause negative outcomes. This can also send a message to policymakers about the types of infrastructure that are needed to deliver certain SDG outcomes and therefore may be more desirable to investors.

- Using the SDGs as a lens for project selection or portfolio building can potentially broaden the investment universe and point infrastructure investors towards the type of assets that are likely to be growth industries in the years ahead. Infrastructure related to the transition to a low-carbon economy is one example, but social infrastructure, such as social housing and education and healthcare facilities, is another asset type gaining more attention because of its potentially positive outcomes.

However, some infrastructure practitioners are more cautious. In our roundtables, a number highlighted that it is important that the SDGs are not seen as an exclusionary framework. This is particularly the case for projects that may initially have more negative than positive SDG outcomes, but which could be reversed if managed correctly. Indeed, from an infrastructure investor’s perspective, some of the most attractive types of assets (from a price and ESG point of view) are those which have poor ESG management or processes, precisely because they can be managed better, deliver stronger financial returns and potentially improve social and environmental outcomes.

Cadent: Injecting hydrogen into the gas network for low emission heating

Several institutional investors hold a stake in Cadent. The UK gas distribution company is conducting a series of trials to inject hydrogen into its gas network to lower the emissions generated through heating buildings in the UK – when burnt, hydrogen emits no carbon dioxide. If fully commercialised, this technology would highlight how an infrastructure asset could reduce current negative outcomes in relation to the environment.

Asset-level KPIs and impact objectives

Direct infrastructure investments typically allow investors to develop more advanced practices for setting outcomes targets in line with the SDGs. In particular, the long-term time horizon of most infrastructure investing fits well with the idea of setting forward-looking KPIs based on desired SDG outcomes, rather than setting targets based on past performance. Tools highlighted by infrastructure investors during our research as useful in this process include the SDG Compass and guidance developed by the Dutch Central Bank 7 .

First State Investments and Forsea

First State Investments has a majority stake in ForSea, the largest ferry operator between Denmark and Sweden, which operates a short distance ferry route between the cities of Helsingør and Helsingborg. The route is a vital maritime transportation link between both countries, with up to 150 departures per day.

Since 2018, FSI has been working with ForSea to develop targets for 2024 and 2030, supporting outcomes in line with seven SDGs. For example, on SDG 13 on Climate Action, ForSea began implementing an energy management system in accordance with ISO 50001:2011, which has assisted towards improved energy performance across the business. All ferries have since achieved Clean Shipping Index (CSI) certification. By switching to alternative fuels, ForSea aims to reduce its Scope 1 CO2e emissions from ferry operations, from a 2018 baseline of 33,500 tCO2e, to 9,800 tCO2e by 2024, to zero by 2030. To achieve this aim, ForSea has converted two of its ferries to battery power – a worldfirst for this type of passenger ferry

Greenfield infrastructure

Investors and advisors in greenfield infrastructure can potentially go further than brownfield investors because they can build SDG outcome objectives into the design and construction of infrastructure. This may involve the deployment of new technology, enhanced stakeholder engagement, and the development of partnerships with different organisations, so that intended outcome objectives, targets and metrics are embedded from the outset of a project. This applies just as much for reducing negative outcomes as it does for achieving or enhancing positive ones.

Global impact partners: Orange Smart City

Investment advisory firm Global Impact Partners used the SDGs as a framework for setting desired social and environmental outcome objectives as part of the planning and design of Orange Smart City, a sustainable development near Mumbai. For example, SDG indicators on water and energy use have led to the integration of smart grids, onsite renewable energy generation, and water efficiency and rainwater harvesting technology. Moreover, monitoring tools, such as sensors, are embedded into the construction to provide ongoing measurement of performance against specific SDG targets and indicators.

There are a range of tools in use within the infrastructure industry which support the design, build and operation of sustainable infrastructure8. These tools are being aligned more closely with the SDGs. For example, the Infrastructure Sustainability Council of Australia’s IS Rating Scheme evaluates “the sustainability performance of the quadruple bottom line (Governance, Economic, Environmental and Social) of infrastructure development”, and sets a baseline for the expected contribution to the SDGs of the asset being rated.

Similarly, several programmes and tools have been developed for use by the public sector when planning and designing infrastructure projects to enhance its sustainability outcomes9. Setting clear government expectations for the intended social and environmental outcomes of projects should drive potential investors to align their own beliefs, practices and targets. This would be a critical step forward in building greater uptake by infrastructure investors.

3. Investors shape outcomes

Overview

It is critical that processes are developed to move from policies and targets to concrete action. Our research highlights several ways in which infrastructure investors are achieving this.

Investment allocation

As noted above, pressure is growing on infrastructure investors to invest in assets that can contribute more to SDG outcomes. At the same time, the lack of specific targets for SDG outcomes being set by asset owners or by investment managers, means that this is still taking place largely on an ad-hoc basis.

Assets are being selected on their risk-return profile first and foremost, with an assessment of their possible SDG-aligned outcomes a secondary or retrospective process. Increasing allocations to infrastructure by asset owners may present an opportunity for LPs and GPs to align interests more effectively in this regard.

Nonetheless, our research highlighted that some organisations are taking a more proactive approach. Given their focus on socio-economic development, development finance institutions are often at the forefront of this. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) ensures that all its infrastructure investments meet at least two of six ‘transition qualities’ that it has defined internally; those qualities have in turn been mapped against the SDGs, ensuring that all investments are made by considering their likely SDG outcomes. Several metrics used by the EBRD to measure progress align clearly with SDG targets and indicators. For example:

- Metrics for ‘Inclusive’ investments include the percentage of women in managerial positions, the same as SDG indicator 5.5.2.

- The percentage of establishments with checking or savings accounts, aligning with SDG indicator 8.10.2 10 .

Infrastructure impact investors

Several infrastructure investors are also building specific ‘impact’ strategies, whose overall objectives – for example, in relation to climate change or on specific social issues – link to the SDGs. For example, SWEN Capital Partners’ SWEN Impact Fund for Transition will assess the positive and negative outcomes of its investments, which focus on biogas production and engagement with the French agricultural sector, to support greater sustainability within the industry.

Investment process

Investors can use SDG outcomes at different stages of their investment process.

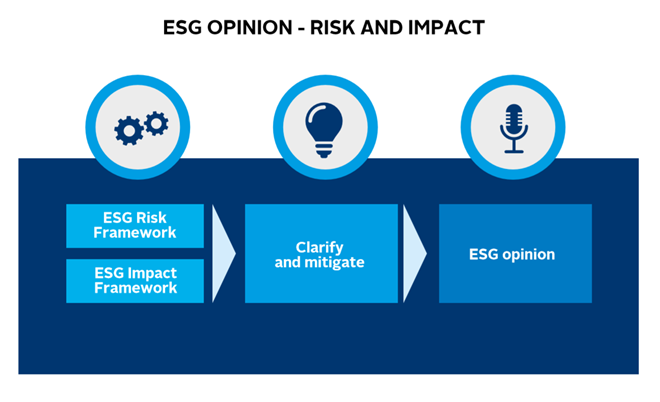

Aviva Investors: Impact overlay

Aviva Investors’ real assets business provides one example of how SDG outcomes can feature in due diligence. It has developed an ‘impact overlay’ to include alongside its standard ESG risk assessment process, so that assessments are made not only of the potential ESG risks but also of the potential positive and negative outcomes that different projects may have. Through this process, Aviva has accepted greater risk in some projects, particularly in emerging markets, in return for greater potential impact. Although not commonplace, the PRI has heard from other investors willing to make a similar trade-off, also in emerging markets.

Figure 4: Aviva Investors’ impact model for real assets investments

Figure 5: Aviva Investors’ impact overlay model for real assets investments

Some organisations have sought ways to align SDG and financial targets during the investment process.

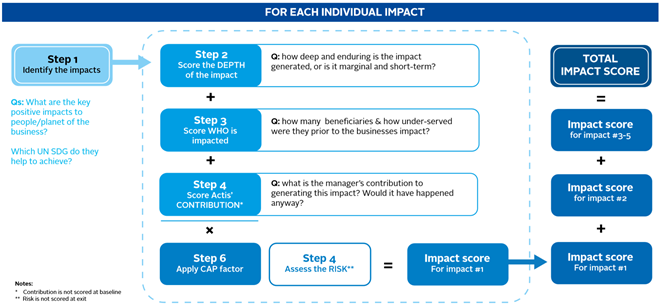

Actis: Impact score

Actis, an emerging markets-focused private equity investor with a focus on infrastructure, has developed the Actis Impact Score, a methodology which it uses to assess the performance of its investments, in terms of targeted outcomes. This score is developed in conjunction with the overall investment thesis, ensuring that financial and impact expectations are closely aligned from the outset of a deal. This methodology has been influenced heavily by a framework developed by the

Impact Management Project

, as have similar ones created by other infrastructure investors.

Figure 6: Actis impact score

Asset management

Private markets – which much infrastructure investing falls under – give investors the potential for much greater influence over the performance of the companies or assets that they invest in, including in relation to SDG outcomes

Investors at the roundtables highlighted that the SDGs can highlight or add nuance to issues that may not otherwise be addressed when managing an asset or engaging with portfolio companies. The SDGs can also encourage investors to be more creative in their asset management approaches than they would otherwise be in order to shape different outcomes.

For example, an investor in a UK-based ports business found that using SDG 4 on Quality Education as a focal point for community-engagement programmes resulted in the building of a stronger pipeline of people into the business, reduced absenteeism and wider benefits for the community.

This example highlights the idea that in infrastructure, investing in line with SDG outcomes can require ancillary investments or activities. Sometimes these may be corporate social responsibility-type activities in support of building and retaining a social licence to operate.

However, others will be more directly business-oriented. One example of the latter discussed at the roundtables was that of a power generation business which needed additional investment in transmission and distribution upgrades to ensure that the power generated could reach its target market reliably.

Roundtable participants also recognised that managing assets in line with SDG outcomes can require different skillsets, financial incentives (for individuals and at an organisation or investment level) and partnerships with external organisations, among other points. These issues are discussed further in the ’Challenges’ and ’Next Steps’ sections of this report.

Performance metrics

Infrastructure investors use a wide range of tools or providers to develop metrics for measuring the ESG performance of their assets. Initiatives such as the Global Reporting Initiative , the Global Impact Investing Network’s IRIS+ tool , the Harmonised Indicators for Private Sector Operations and GRESB were the most frequently cited during our roundtables.

These initiatives are increasingly aligning their existing metrics to the SDGs or developing new ones where appropriate, to make it easier for investors to assess the performance of their assets in this regard.

Some organisations are also using certain indicators or targets within each SDG as metrics. For example, toll road operator Transurban uses a series of specific SDG indicators on issues they consider critical to their operations, such as road safety, gender equality, decent work and economic growth, among others, to either directly report against or use as the basis for establishing internal policies and programmes.

Other organisations use a mix of qualitative and quantitative information to measure outcomes. Many infrastructure investors send annual ESG questionnaires to all their portfolio companies and investees as a way of gathering detailed information about their approaches and performance. In some cases, these are being adapted to assess outcomes in line with the SDGs. This reflects the view among several roundtable participants that assessing the outcomes of a particular asset or investment does not always require new metrics or datasets, but rather a different interpretation of the same information, from an outcomes perspective.

The investors we consulted agreed that the wide range of metrics and reporting frameworks available, together with the diversity of the infrastructure asset class, can make it difficult to choose commonly agreed metrics to easily compare the SDG performance of different assets. These challenges will be discussed in more detail later in the report.

Blackrock: Placing a value on SDG metrics

BlackRock’s Global Renewable Power funds use SDG-mapped metrics from the IRIS+ database to assess outcomes. Multiple metrics, such as tons of CO2 emissions avoided, jobs created or water saved, are translated to dollar values to enable comparison across different investments, and to allow for their consideration throughout various phases of the investment process. This conversion of metrics into dollar figures and alignment with the SDGs allows BlackRock to implement an integrated approach, rather than one that is used solely as a post-investment reporting tool.

Engagement with policymakers

Much infrastructure investment is in regulated assets or through some form of relationship with governments, such as concessions or private-public partnerships. More than most other asset classes, infrastructure investors are therefore required to engage with governments on a regular basis. This engagement has traditionally focused on financial risks and outcomes; the alignment of interests on sustainability issues is generally far less advanced.

Nonetheless, there are increasing examples of interactions between infrastructure investors and policy-makers on the SDGs, whether government- or investor-driven.

One government agency in the UK has taken measures to build the SDGs into the heart of its sustainability strategy. In practice, this means:

- ensuring that all KPIs and performance measures are quantified against the SDGs;

- building the SDGs into tender processes;

- using the SDGs as a frame for understanding what community needs are and building those into the investment pipeline.

This strategy:

- frames its interactions with infrastructure project developers and investors;

- sets clear expectations for the outcomes it hopes to achieve through each project, and

- forces those bidding on projects to adapt their own processes and thinking to better align with the SDGs.

This top-down approach from government is also becoming more common at a national level, with sustainability considerations, particularly around climate outcomes (such as Canada’s ‘ Climate lens ’ for infrastructure investments), now featuring in the development of national infrastructure strategies 11 .

As this practice becomes more advanced, it should better define engagement between infrastructure investors, project developers and government on how to ensure that expected social and environmental outcomes are achieved.

Bringing people to the table

During the roundtables, we heard how one US city administration has begun a series of regular meetings with businesses and the financial sector to explore how the public and private sectors can work together more effectively to deliver better sustainability outcomes through its planned infrastructure projects.

Several investor roundtable participants agreed that investment exclusion lists (based on ESG or outcomes-based considerations) can send a strong signal to government about the ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ type of infrastructure projects. They also highlighted that projects with a strong track record on environmental and social performance, going beyond current regulatory requirements, can encourage governments to adopt tighter environmental and social regulations that would favour better-performing infrastructure investors or operators.

Finally, some organisations are also seeking to use the positive outcomes of their investments and operations as a means of engaging with governments for more explicit business purposes: by showing that they can be trusted, value-adding partners, these organisations hope to extend existing concessions and create new investment opportunities.

Disclosure and reporting

Regardless of the type of approach taken, almost all infrastructure investors consulted through our research recognised that the SDGs have become the common framework for assessing their environmental and social contributions. There is, therefore, a baseline for concerted action across the sector. Moreover, roundtable participants agreed that reporting requirements around the SDGs will only become more demanding in the years ahead.

However, current approaches are mixed. In the absence of formal requirements, whether by asset owners or regulators, infrastructure managers are reporting in whatever format they deem most appropriate. This typically falls into two broadly defined approaches:

- Reporting focusing on an organisation’s broad commitment to the SDGs, identifying, for example, which goals it aligns with through the type of assets invested in and its general approach to asset management. This is still done largely for communications purposes.

- Reporting highlighting progress towards more precise outcomes, by highlighting metrics used and the overall methodology for assessing the impact of their individual investments or overall investment strategy. Many managers recognise that this type of reporting has been adopted to anticipate and influence future investor or regulatory requirements, but it also means that reporting can differ hugely from one manager to the next.

GRESB: SDG report-generated pilot tool

As mentioned previously, GRESB has mapped its Infrastructure Asset Assessment to the SDGs at the detailed target and indicator level, to provide an indication of how different infrastructure assets may contribute positively or negatively to different goals. Based on this mapping it has developed a pilot tool that allows a report to be generated from GRESBreported data, which describes the positive and negative contributions that any asset or portfolio is making to the SDGs. It also compares these contributions to that of a relevant peer group.

Challenges

This section considers a more granular list of key gaps – most of which were highlighted during the investor roundtables – that should be addressed to support infrastructure investors in shaping outcomes in line with the SDGs.

The previous section of this report highlighted several ways in which infrastructure investors are integrating the SDGs into their investment processes. However, significant challenges also persist for this to become widespread, meaningful and consistent.

At a high level, further awareness of the SDGs needs to be built among investors, while the fact that the goals were originally conceived for governments can pose difficulties for investors on how best to approach them. At a more granular level, these are:

Data gathering

The multiple ways in which infrastructure investors are considering the SDGs in the context of their investment approaches reflects the lack of a clear industry standard or guidelines. However, it also reflects a more fundamental issue around the quality and availability of data from portfolio companies and individual assets, making it difficult even for the most advanced practitioners to assess their outcomes and report adequately.

This lack of data was cited across all the roundtables the PRI hosted, and builds on the challenges that many infrastructure investors already face in obtaining good data to inform their existing ESG processes. Common gaps highlighted through our discussions and other research, and key areas that must be addressed, include:

- Assets in emerging markets: although developed markets remain far from perfect, gathering information from assets in emerging markets was often highlighted as particularly challenging, as the processes for managing ESG issues among many companies and assets are still nascent.

- Inconsistency across assets and investors : the ways in which different investors set targets or choose metrics to monitor outcomes creates inconsistency in how data is gathered (and ultimately reported). This also applies to individual investors, particularly larger investors, with assets in a range of infrastructure sectors and geographies.

- Lack of control: the challenge of data gathering is often amplified for infrastructure investors with only a minority stake in a company or asset – can they use that minority position to gather the right type of data to enable them to make proper decisions or influence SDG outcomes?

- An extra burden: the SDGs can be perceived as an additional and unnecessary burden by portfolio companies or assets, particularly those which do not have good systems for identifying ESG issues in place.

- Asset-level vs portfolio- and fund-level data: issues with asset-level data are amplified when it comes to assessing SDG outcomes at a portfolio or fund level, and this in turn causes problems for investment managers and asset owners seeking to report accurately on their overall ‘contribution’ to the SDGs.

Aligning SDG outcomes and financial considerations

Questions were raised across the roundtables about the challenges of securing buy-in, whether internally, particularly from investment teams, or from clients, to focus on shaping outcomes in line with the SDGs. These conversations typically had two areas of focus:

- Valuing outcomes: these discussions assessed whether it is both feasible and necessary for a value to be placed on outcomes (particularly social ones) for the SDGs to be adopted more widely and in a more meaningful manner 12 . Proponents argue that such valuations may result in more realistic costs of capital and make a stronger case for allocating capital to investments with greater potential for positive outcomes. Opponents highlight that other potential impacts on infrastructure assets’ valuations, particularly stemming from political or regulatory changes, may outweigh those related to environmental or social outcomes, and so weaken the case for doing the former.

- Internal alignment and incentives: investment and asset management teams are not incentivised to focus on SDG outcomes, nor is there enough alignment between these and ESG and sustainability teams. Those with more in-depth approaches to the SDGs have emphasised the need to build consideration of the goals more directly into investment discussions (as highlighted by some of the examples above), but too often these remain separate processes.

Setting consistent outcome objectives along the investment chain

There is widespread inconsistency through the investment chain on what SDG outcomes are expected and targeted. As highlighted previously, there are few examples of asset owners building detailed questions or expectations around SDG outcomes into their mandates and infrastructure manager selection processes.

However, the issue goes beyond that. Given the different ways in which infrastructure practitioners are assessing their SDG outcomes and setting related targets and policies (or not), it is probable that several participants in the investment chain are seeking to achieve different outcomes for that same asset.

For example, an asset owner with infrastructure investments may have a set of SDG outcomes, based on the core values or mission of the organisation, that it wishes to achieve across its portfolio. In contrast, an infrastructure operator or an investment manager with direct control over an asset or portfolio company may understand their SDG outcomes in more operational terms. This assessment of SDG outcomes is more likely to be derived from the ground up (at the project level), often based on social and environmental impact assessments and through stakeholder consultations.

This misalignment is to some extent unavoidable given the different roles and responsibilities within the investment chain, but there are few substantive efforts being made to bridge the gap. During our research, we heard of very few instances where an asset owner and investment manager had had detailed conversations about potential infrastructure opportunities together so that eventual deals are aligned with desired SDG outcomes.

Government-investor engagement

We have previously highlighted how some engagement between government and infrastructure investors is taking place around the sustainability of infrastructure projects. However, most of this appears to happen on an individual basis in relation to single projects. In contrast, there is a lack of engagement on more systemic issues. These include:

- the role that private investment can play in delivering infrastructure that supports the achievement of SDG outcomes, and

- how infrastructure projects and systems are planned, designed and commissioned in a way that private and public sustainability and financial interests can be aligned.

In certain markets – for example, Canada, through the Canada Infrastructure Bank – there are forums through which the public and private sector can engage more directly. However, these types of platforms are not widespread. Consequently, there will likely continue to be misunderstanding and mistrust between government and infrastructure investors, as exemplified by the dispute between the UK water regulator Ofwat and water companies (and their institutional investors) over their investment plans, operational performance and expected returns14.

Internal and external skillsets

Investing with SDG outcomes requires new skillsets for infrastructure investors. Some of these will need to be developed internally, to enhance the work of existing ESG and investment teams; other skills or expertise may need to be obtained through developing new partnerships or networks with external organisations.

- Internal: at a high level, integrating SDG outcomes requires a similar skillset to existing ESG processes. However, the more detailed approaches become, the greater the need for extra levels of technical expertise on environmental and social issues. Assessing the risk that an infrastructure project will harm gender equality, for example, is different to having the expertise to build an engagement programme or operate the project in a way that maximises positive outcomes and minimises negative outcomes.

- External: groups such as local communities, labour organisations, NGOs, impact experts, and government can be important partners in delivering SDG outcomes, by providing better local and technical knowledge and ensuring that programmes can be targeted effectively. However, relations between infrastructure projects, investors and such groups are often characterised by mistrust and misperceptions, and so undermine the potential for them to work together effectively.

Greenfield vs brownfield investing

The majority of infrastructure strategies target investment in brownfield assets in developed markets. Among many asset owners, there is limited appetite for greenfield investments, which carry greater development risk, particularly in emerging markets. This can be an obstacle when investing with SDG outcomes. As highlighted previously, greenfield investments often allow investors and project developers to set outcomes objectives in the planning, design and construction of assets, rather than having to take action retroactively, as is the case with brownfield investments.

With major new initiatives and commitments being implemented in the coming years, which will require significant investment in new infrastructure – for example, the European Union’s Green New Deal 14 – investors will need to assess how they can allocate more capital to greenfield infrastructure, including by reconsidering their risk appetite. It will also require support by government and regulators, through subsidies or other financial mechanisms to boost the bankability of projects.

Investor collaboration

The Investing with SDG Outcomes report emphasises the need for collective investor action to achieve the SDGs, not just action at the individual investor level. There are few examples of collective action by infrastructure investors in this regard.

Several French infrastructure investors have collaborated on the 2-infra challenge , a programme to develop a methodology to measure alignment of infrastructure portfolios against a two-degree climate scenario and associated climate risks. In Denmark, a group of private investors have partnered with the government and the Investment Fund for Developing Countries (IFU) to set up the Danish SDG Investment Fund, many of whose investments are in infrastructure such as renewable energy 15 .

Small groups of investors have also participated in forums or initiatives in areas such as blended finance – particularly aimed at driving more investment into emerging markets – or for creating international standards around sustainable infrastructure. These include the Global Infrastructure Forum , led by a coalition of multilateral development banks, and the G20 Quality Infrastructure Principles .

Overall, however, industry collaboration in relation to the SDGs is limited. In part, this stems from several of the issues highlighted elsewhere in this report – with individual investor action often still in its early stages, it is not easy to take collective steps, particularly where that involves addressing themes or issues that may be outside the traditional focus of infrastructure investment.

Next steps

This section identifies some high-level areas for action by infrastructure investors, specifically addressing the Challenges identified in the previous section.

The previous sections of this paper have highlighted the progress made so far by infrastructure investors in investing with SDG outcomes, but also the very real gaps that still exist within practices in the sector.

Both need to be addressed if the potential for infrastructure investment to contribute to the SDGs is to be fulfilled.

More broadly, the PRI will assist signatories seeking to shape outcomes in line with the SDGs, across the proposed framework, for each of the investor actions, and to support disclosure and reporting. More details of the work to be carried out are provided in Investing with SDG outcomes: A five-part framework .

Areas for action by infrastructure investors and other market participants

| Challenge | Example actions | Taken by |

|---|---|---|

| Data gathering | Greater uptake of existing tools and metrics, collaboration to further enhance their applicability and consistency across infrastructure sectors and geographies. |

|

| Aligning SDG outcomes and financial considerations |

Deeper consideration of sustainability outcomes at different stages of investment, closer collaboration between sustainability and investment teams. Regulations to steer investors to develop closer alignment of financial and sustainability considerations (e.g. the EU Sustainable Finance Taxonomy) |

|

| Setting consistent outcome objectives |

Closer alignment between asset owners and investment managers on SDG outcome objectives through selection, appointment and monitoring processes and ongoing dialogue. Develop processes to identify salient ESG issues – those most at risk of causing negative impacts through an investment. |

|

| Government-investor engagement |

Enhance existing dialogue on infrastructure pipelines and project design to include sustainability factors. Explore collaboration opportunities with multilateral organisations to support raised standards, policy changes |

|

| Internal and external skillsets |

Internal training and hiring policies reflect need for enhanced skillsets on ESG issues. Explore partnerships with external partners to bring in skills or experience where unavailable internally. |

|

| Greenfield vs brownfield investing |

Draw on experience of sectors such as renewable energy to identify opportunities for greater greenfield investment, to ‘embed’ outcomes from outset of projects. consultanciesConsider how strategic asset allocation decisions can be adjusted to allow greater investment in higher-risk greenfield projects. |

|

| Investor collaboration |

Join or continue to support industry initiatives (including those developed by the PRI) to foster greater collaboration – individual investor actions will not be enough to achieve the SDGs. |

|

Downloads

Bridging the gap: How infrastructure investors can contribute to SDG outcomes

PDF, Size 1.78 mb弥合差距:基础设施投资者如何助力实现SDG结果 (Chinese)

PDF, Size 2.41 mb

References

1 The roundtables and interviews were held on a confidential basis to encourage more open discussion. References to specific organisations in the remainder of the document are based on open-source research or with the contributors’ express permission.Massive new infrastructure investment is fundamental to the achievement of the SDGs. As a paper by the Economist Intelligence Unit highlights: “From transport systems

2 Preqin Factsheet on 2019 Infrastructure Fundraising & Deals Update, 9 January 2020

3 See the PRI report: Are national infrastructure plans SDG-aligned and how can investors play their part

4 The 17 SDGs in a list of 169 targets. Progress towards these targets is tracked by 232 unique indicators. See UN Statistics Division’s Global indicator framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

5 As defined by Mott MacDonald: “Direct impacts occur through direct interaction of an activity we undertake. Indirect impacts are those which are not the direct result of a project, often produced as the result of a complex impact pathway. Induced impacts usually have an even more complex relationship with the action under assessment and represent the growth-induced potential of an action.”

6 For example: Foresight aannounces first closing of European-targeted, sustainability-led energy infrastructure fund securing commitments of €342 million

7 Further tools can be found in Investing with SDG outcomes: A five-part framework

8 Examples include: SuRe, ISCA, Envision, BREEAM,

9 For example: Global Infrastructure Hub’s Reference Tool on Inclusive Infrastructure and Social Equity, SOURCE, a “multilateral platform for quality infrastructure” and Infrastructure Canada’s Climate Lens

10 European Bank for Reconstruction and Development: Transition Report 2019-20

11 Are national infrastructure plans SDG-aligned, and how can investors play their part?

12 There are ongoing efforts to develop tools that can quantify the environmental and social costs and opportunities of infrastructure projects. These include the International Institute for Sustainable Development’s Sustainable Asset Valuation tool, which seeks to “demonstrate why sustainable infrastructure can deliver better value-for-money for citizens and investors”. For more details see: IISD’s Sustainable Asset Valuation (SAVi)

13 See, for example: FT’s article Ofwat faces biggest battle with water companies since privatisation

14 See also PRI briefing: Investor priorities for the EU Green Deal

15 Danish SDG Investment Fund kicks off with Better Energy solar project