By Stefano Giglio, Yale School Of Management, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), and Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR); Theresa Kuchler, NYU Stern, NBER, and CEPR; Johannes Stroebel, NYU Stern, NBER, and CEPR; Xuran Zeng, NYU Stern

Over the past decade, there has been an increasing focus on understanding how our economy and the environment interact. Much of this research has explored how climate change affects economic activity and asset values. But climate change is only one dimension of the feedback loops between the economy and the health of our planet. In our latest paper, we study a different and equally important dimension: the economic risks associated with biodiversity loss.

Our key questions include: can we quantify biodiversity risk? How does it differ from climate risk? And is biodiversity risk already reflected in asset prices?

What is biodiversity risk?

Humans rely on biodiversity – defined here as the sum total of genes, species, and ecosystems – to survive and thrive. For example, diverse ecosystems are key to the production of food, while many medicines are derived from natural compounds found in plants, animals, and microorganisms. The recent losses of ecosystem services have been estimated to cause damages of USD$4trn to USD$20trn per year.1

In addition to these physical risks, there are ‘transition risks’ from regulatory responses to biodiversity loss. One key example is the recent COP15 conference in Montreal, which led to an international agreement to put 30% of the planet under protection by 2030. These transition risks can have substantial effects on economic activity and asset values.

Despite its importance, biodiversity risk has been understudied in economics and finance research in part due to its complexity and the challenges in how to measure it. In our paper, we systematically measure aggregate biodiversity risk and release several measures of how exposed firms and industries are to these risks, based on information such as firms’ 10-K statements (i.e., their annual reports). These measures generally line up with investors’ views about biodiversity risks; they are also reflected in asset prices.

Do people worry about biodiversity risk?

In short, yes. We conducted a broad, global survey of the perceptions of biodiversity risks among finance academics, professionals, public sector regulators, and policy economists. Around 70% of respondents perceived physical and transition biodiversity risks to have at least moderate financial materiality for firms in the US, with private sector respondents reporting the highest perceived financial materiality.

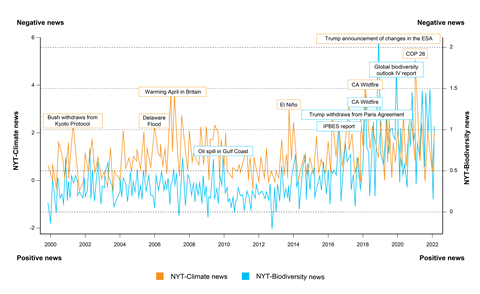

We also analysed the news coverage around biodiversity in the New York Times, from 2000 to 2022, to better understand when bad news about biodiversity risks occurs. We created a corresponding news index to capture periods of bad news about climate change to explore commonalities and differences in climate and biodiversity risk realisations.

As shown in Figure 1 below, we found that negative biodiversity-related news events (e.g., Trump’s announcement of changes in the Endangered Species Act, or the oil spill in the Gulf Coast) did not generally coincide with spikes in the climate news index, while negative climate-related news events (e.g., Bush’s withdrawal from the Kyoto Protocol, or a Delaware flood) did not result in spikes in the biodiversity news index. There are some common events (e.g., wildfires), but the overall correlation between the two indices is low, suggesting that risks from biodiversity-related and climate-related events are distinct and therefore need to be studied and understood independently.

Which industries are most exposed to biodiversity risk?

Different sectors vary in their dependence on natural capital, which links to their physical biodiversity risk exposure. They also differ in terms of their effects on the environment, and therefore their regulatory biodiversity risk exposures.

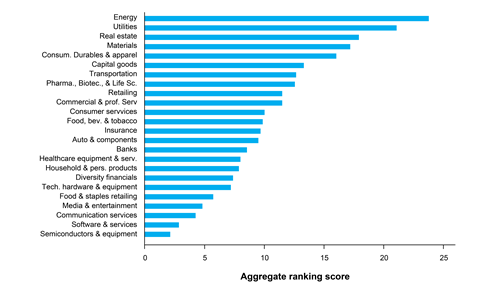

We propose several ways to quantify different firms’ and industries’ biodiversity risk exposures. Our first measure looks at firms’ 10-K statements, which often disclose both physical and transition risks. For example, energy companies mention being exposed to biodiversity transition risks related to drilling and refining activities, which can affect the ecosystem and are potentially a target for future regulations. Utility firms face regulations on species and habitat protection, and the real estate industry faces restrictions on developments in areas with high biodiversity. Firms also report facing physical biodiversity risks, including pharmaceutical companies relying on biodiversity for drug discovery.

We construct other measures of industry-level exposures using information from our expert surveys and portfolio holdings of biodiversity funds. Figure 2 shows the biodiversity risk exposures across industries, combining our different measures into a composite industry-level exposure measure. We found that sectors with the highest biodiversity risk exposures include energy, utilities, and real estate, while semiconductor, software, and communication services sectors have minimal exposures.

Are biodiversity risks incorporated in equity prices?

We also explored whether equity prices reflect biodiversity risk exposures. To do this, we formed a portfolio of long positions in industries with low biodiversity risk exposures and short positions in industries with high biodiversity risk exposures.

If biodiversity risk is priced in, the return of these portfolios should covary with innovations in the aggregate biodiversity news index, behaving like a hedging portfolio. We find positive correlations between the returns of our biodiversity hedging portfolios and innovations in the biodiversity risk index, indicating that biodiversity risk has been at least partially priced in equities over the past decade.

Biodiversity risks versus climate risks

Throughout our paper, we explored the relationships between biodiversity and climate risks. Although these risks are conceptually separate – biodiversity risk focuses on threats to Earth’s variety of life, and climate risk involves adverse outcomes from climate change – they are interlinked. Climate change can exacerbate biodiversity loss, and biodiversity loss can contribute to climate change, for example through the depletion of carbon sinks.

Given the recent interest in climate change and its economic implications, it is important to distinguish climate and biodiversity risks qualitatively and quantitatively. We achieved this in several ways. First, we showed that the aggregate biodiversity index behaves differently from similarly constructed climate indices. Second, we documented that climate and biodiversity exposures are only weakly related in the cross-section of industries (for example, renewable energy firms benefit from climate transition risk realisations, but suffer from biodiversity transition risk realisations). Finally, we showed that portfolios built for hedging climate risk do not perform well at hedging biodiversity risk, and vice versa.

In conclusion, biodiversity services are essential for the economy, and risks associated with biodiversity loss can affect firms through various channels. Yet, those risks can be difficult to quantify and study systematically.

The goal of our paper was to introduce measures of aggregate biodiversity risk as well as measures of firms’ and industries’ exposure; to connect and validate these two; to study the pricing of biodiversity risks in financial markets; and to publicly release our biodiversity exposure measures at www.biodiversityrisk.org. We hope our findings will facilitate more research on this important topic.

The PRI’s academic blog aims to bring investors insights from the latest academic research on responsible investment. It is written by academic guest contributors. Blog authors write in their individual capacity – posts do not necessarily represent a PRI view.

References

1 Kapnick, Sarah, (2022) “The economic importance of biodiversity: Threats and opportunities”