Companies are working on greater data disclosure as well as adopting greenhouse gas reductions and renewable energy usage targets. But there is tension between credit analysts’ need for standardised data, and companies’ desire for recognition of their specific circumstances and challenges.

This was one of the main conclusions of a workshop held in January 2021 with investors, credit rating agencies, and 20 companies from a range of industries to discuss ESG engagement and disclosure in the sub-investment grade debt market.

The event was the second organised with the European Leveraged Finance Association[1] covering sub-investment grade borrowers, and the sixth in the PRI’s Bringing credit analysts and issuers together series overall. It attracted over 100 market participants - for a full list of participating organisations, see the box below.

Talks were held under the Chatham House Rule, and were structured around a set of guidelines that were criculated to participants prior to the event, and tailored by sector.[2] Following the workshops conducted in 2020, the PRI and ELFA published a series of sector-specific ESG Fact Sheets, and will add to these over the coming months. These are designed to support borrowers in preparing ESG disclosure, and to facilitate engagement between investors and corporate borrowers.

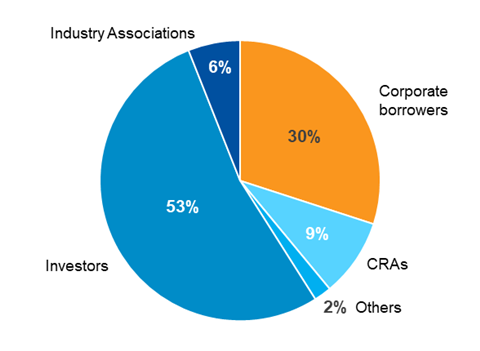

Figure 1: Event participants by type

Workshop participants

|

Sub-Investment grade borrowers |

|||||

|

Chemicals |

|||||

|

Communications infrastructure |

|||||

|

Industrials |

|||||

|

Retail |

|||||

|

Technology and software |

|||||

|

ERT |

|||||

|

Investment institutions |

|||||

|

Credit rating agencies |

|||||

|

Industry associations |

|||||

This report contains highlights from discussions held during the breakout sessions with companies in the chemicals and industrial sectors.

These sessions were held at the same time as others focused on the retail, communications infrastructure and technology/software sectors, which are summarised in Part 2a of this article. Some observations were common or were covered in other articles of the series. In this report we address only new or sector-specific themes, and report on emerging solutions that participants have begun to consider.

Energy: Data and targets

Companies are working on greater data disclosure as well as adopting greenhouse gas reductions and renewable energy usage targets.

They are responding to investors’ increasing demand for data on companies’ carbon footprint, energy consumption and energy mix (derived from renewable or non-renewable sources). At the same time, they are reacting to the changing preferences of other stakeholders (such as customers or local communities).

But there is tension between credit risk analysts’ need for standardised data that can be compared between companies, and the companies’ desire for recognition of the specific circumstances and challenges they face. Companies point out they may operate many plants in different regions and jurisdictions, with different degrees of energy efficiency; and the option of switching energy source may not be available.

Further, companies noted that there is additional nuance at the product level, for example, a product may be more energy-intensive, but may last longer. Companies would prefer analysts to examine their individual year-on-year improvement, and urge caution with peer benchmark comparison.

In contrast, credit analysts are looking for more comparable figures at the company or group level, not only for relative value analysis purposes but also because they cover various issuers at the same time, and therefore do not have time or the resources to assess many details or to look for them from multiple sources.

The transition to net zero carbon emissions is another challenge for firms. It can be expensive, and soon companies may also have to deal with a rising carbon price.

Companies note that data disclosure is a starting point, but a dynamic analysis is more important than static figures, to form an understanding of how energy needs will evolve in the future and the pace at which the transition will occur.

“We hear a lot about the transition and less about its speed. It is widely assumed that this will be linear, but climate risks can affect the cost of capital in different ways.” — Investor

Many companies have already started setting goals, some of which are science-based, although they may not have been made public yet. One company started out by sharing sustainability reports with investors, but realised it needed to make them public so that ESG data providers could access them.The targets can be longer-term — for example, achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2050 — and therefore harder to link to credit quality.

However, more immediate goals also exist, for example relating to Scope 1 emissions (direct emissions from sources controlled or owned by the firm) and Scope 2 emissions (indirect emissions associated with buying electricity, steam, heat and cooling). It can be harder to disclose and set targets for Scope 3 emissions, which are indirect emissions across the value chain that are not incorporated in Scope 2.

Participants noted that the chemicals sector did not disclose Scope 3 emissions well. Measuring Scope 3 emissions often requires cooperation between different entities, and the difficulties in measuring them may complicate comparisons between companies.

The need to make a life-cycle assessment of products was raised across several breakout sessions. Companies in the chemicals sector, in particular, are asking analysts to take into account the contribution their products are making to the transition to a low carbon economy.

Tools for decarbonising include using clean energy sources (including self-generated energy), recovering the energy used in the distillation of chemicals, and making operating assets more efficient. Firms may be able to receive help in the form of government subsidies. One participant commented, however, that it was more challenging to transition to green electricity in certain regions, for example Asia.

“Scope 3 needs cooperation across the value chain. It’s harder to get meaningful data on.” — Corporate borrower

Emerging solutions

It may be some time before firms achieve carbon neutrality, but loans where the interest rate is tied to carbon targets offer one way to encourage lower carbon emissions. Furthermore, companies should not only disclose targets but also how they have determined them.

Going beyond CO2 emissions: Plastics and water

Companies in the chemical and industrial sectors noted that the use, disposal and environmental impact of plastics as well as water usage should receive more focus from an ESG perspective, even if finding useful or comparable metrics is more difficult than for CO2 emissions.

Plastic is widely used across the economy. Its production can have adverse environmental impact, and more sustainable substitutes may be available. Furthermore, much plastic is disposed of in landfill sites, or incinerated, when no longer required. Companies’ plastic risk is related to whether they are able — or required — to substitute other materials for plastics, and how difficult this is for them.

However, in some instances, plastic can have a positive environmental impact. For instance, acrylic glass is used in electric vehicles to make them lighter, or in greenhouses to make them more efficient in their food production.

Participants also discussed the role of governments, which can encourage reduction in the use of plastic, its substitution with other materials, more recycling, and better waste management. The government can also influence consumer behaviour: shifting consumer expectations and demand would force companies to adapt.

One CRA observed that for now, the main risk for plastic over the medium term does not stem from dwindling demand. Efforts to reduce single-use plastics will not offset demand linked to demographics and GDP growth. Furthermore, there is no perfect substitute for plastic and mechanical recycling produces lower-grade materials. However, should recycling techniques improve in the future, and investment in the necessary infrastructure increase, this could create risk upstream in the industry.

“We know that a circular economy in plastics will develop to try to get recycling rates up to the level of paper and aluminium.” — Corporate borrower

Water was also raised as an issue: both its usage and its treatment. It can be used less, and it can be recycled after use, for example using waste water in irrigation. It is an important issue for the chemical sector on both fronts, whereas for the industrial sector, water waste is more relevant than water consumption. One company participant said that it has already collected the necessary information to start reducing water waste, but it is mostly done at the local level, rather than globally.

Some participants observed that a desire to perform well on sustainability scores calculated by ESG data and service providers or to be included in a low carbon emission index may detract a company’s attention from disclosing KPIs that are more operational or strategy driven.

“When assessing ESG pillars, everyone jumps to CO2 emissions, but they might not be the most relevant metric to focus on.” — Investor

Emerging solutions

The environmental discourse is beginning to go beyond climate change, but there is little alignment yet between credit analysts and borrowers on the sector materiality map. Therefore, more engagement is needed for analysts to better understand companies’ processes and planning.

Corruption and bribery

Issues related to corruption, compliance and bribery can pose significant legal and reputational risks, and were discussed in the context of governance assessment.

Corporate strategies to combat corruption can involve issuing guidelines, training staff regularly, conducting due diligence when embarking on M&A, and having appropriate whistleblower schemes. Companies may also wish to ensure senior managers stress the importance of compliance procedures.

In certain regions where the risk of corruption and bribery is higher, a company could deploy more compliance officers. One company said that they have several committees now in place, including on ethics, audit, compensation, strategy and, more recently, also compliance.

“I know how much time investment analysts have to spend on anti-corruption training ourselves. If a company has similar mandatory training, then that shows it is taking it seriously.” — Investor

Some companies said they were hardly ever asked about anti-bribery policies, even though investors said these were important in their analysis. Some information about anti-bribery policies may already be easily discoverable, but analysts mentioned they needed to request further information from companies to more adequately assess board structure, past litigation and controversies. Governance information may also be harder to access when it relates to first-time issuers.

“We search for controversies as a signal for potential future risks.” — Credit rating agency

One investor wondered whether legal costs, through either legal fees or fines, were a good benchmark to assess this risk. A company participant noted that this might not necessarily be the case as a broader sales base, i.e. not being reliant on any one client or small group of clients for a large proportion of sales, could reduce litigation risk. Another investor suggested that the use of third-party checks could offer reassurance, for example an external review of a company’s systems.

Emerging solutions

It was suggested by participants that companies could standardise disclosure on board structure. The composition and the independence of board directors as well as the existence of anti-corruption policies are seen as key indicators that are inherent to credit risk. Assessing compliance with policies should also be part of the analysis.

Health and safety

Where health and safety standards are inadequate, the resulting accidents may cause financial costs as well as human suffering for a firm’s employees. This is a particularly relevant issue in the chemical and industrial sectors, which are both asset intensive.

There was discussion on how to measure and compare health and safety standards across organisations. Commonly used metrics include the total recordable injury rate (TRIR) and lost time incident rate (LTIR). One company said it was focusing on the frequency rate of accidents as a target, and would share goals publicly. One way to measure the impact of lax health and safety procedures is through the financial cost, for example, the litigation costs or the effect of lost working time.

Companies at the workshop pointed to the difficulty of drawing inferences from differences between firms, echoing remarks made during the energy discussion. A CRA analyst participant agreed that it was difficult to collect comparable information on health and safety. One factor that makes comparing figures across companies more challenging is that regions may have different health and safety standards, particularly within a company with operations across different locations. For this reason, comparisons may make more sense on a regional basis.

One firm had key performance indicators related to safety for individual countries, but said it was difficult to provide group data due to different rules across jurisdictions. However, the company is looking at metrics that would apply a common standard across countries.

Rather than looking to be measured against peers, one company preferred to assess itself versus its own past performance.

Where companies use contractors — who are not directly employed by the firm, but carry out work for it — this can be another complicating factor in assessing risk. One company said its supplier code of conduct contained requirements related to safety.

Companies can also tie executive pay to safety metrics. It was reported that this is relatively uncommon in Europe, although senior managers typically oversee safety. By contrast, in North America the compensation of senior managers may be linked to safety records.

As for the investor engagement that companies receive on health and safety, firms reported that they are rarely asked about the topic and one company was uncertain whether investors found or used the information that the company provided. Another company said that health and safety was not a topic of engagement with CRAs either. However, the participating investors confirmed that health and safety policies were important to their analyses.

Meanwhile, a credit analyst suggested that firms put KPIs relating to health and safety in the offering memorandum. An example was given of an industrials company in the US that advertises its health and safety record as a marketing tool and a positive factor for its creditworthiness.

“You can never find the perfect peer, but benchmarking a company to its own track record can be quite relevant.” — Corporate borrower

Emerging solutions

This is an area where a lot of data and metrics already exist, partly because of regulatory requirements. Companies should consider following the examples of some of the participating companies, which already disclose some KPIs in offering memoranda, investor presentations and press releases. However, the issue of comparability remains.

Sector-specific considerations

The discussions highlighted several considerations specific, but not unique, to the industries of the companies represented. The following are examples of areas where investors may request more information for ESG analysis, and where borrowers may seek to improve disclosure. These are outlined below:

|

Chemicals |

Industrial |

| Plastics are a key risk: Issues around single-use products, recycling and waste | Carbon emissions may be significant |

| Difficult to assess Scope 3 emissions, which could be significant | The value chain encompasses many companies; this affects the Scope 3 emissions calculation |

| Water, waste and hazardous material management is in focus | Health and safety of employees is a highly relevant issue; KPIs are total recordable injury rate (TRIR) and lost time incident rate (LTIR) |

| So too is chemical safety exposure and management | |

| Opportunities and challenges in the ‘circular economy’ as consumers seek more sustainable products | |

| A lack of gender diversity |

Downloads

References

[1]The ELFA is joined in this initiative by the Loan Market Association (LMA).

[2] The PRI initially published these guidelines after the Paris workshop, the first of the series. They will be refined as the workshops continue.