Securitised products are backed by different types of debt (mortgages and consumer or corporate loans), making it more difficult to integrate responsible investment practices. This guide looks at three areas where investors can focus their efforts: investment analysis, thematic-focused strategies and engagement and collaboration.

Contents

Executive summary

This guide provides an overview of the state of play for how investors are integrating responsible investment practices in securitised assets. These are debt securities created by bundling together different types of debt (including mortgages, consumer or corporate loans) and converting them into tradeable securities.

The guide covers the most common segments of the securitised market:

- residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS)

- commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS)

- asset-backed securities (ABS)

- collateralised loan obligations (CLOs)

The complex nature of securitised debt has slowed the introduction of responsible investment approaches, however we have seen progress in recent years.

The first section of the paper reviews the significant size of the securitised debt market and notes its prevalence in investor portfolios due to its inclusion in major fixed income benchmarks. The important role it plays in financing a more sustainable economy is also explored, tied to the unique features of this asset class.

The second section explores how responsible investment practices in this asset class have evolved on three fronts: investment analysis, thematic investing and engagement and collaboration. The third section looks more closely at how these three practices are applied in each type of securitised debt subsegment. The paper closes with key actions asset owners might want to consider when allocating towards securitised debt. A list of additional resources is also provided.

For any questions or feedback, please contact the fixed income team on [email protected].

“The securitised debt market has a key role to play as a catalyst in mobilising capital to finance a more sustainable economy. It is therefore important for this asset class to be on the radar of responsible investors.”

David Atkin, CEO, Principles for Responsible Investment

Following the 2021 publication of our inaugural guide for this asset class, ESG incorporation in securitised products: the challenges ahead, we have seen improvements in data availability and the issuance of sustainability-themed debt. However, feedback from signatories, including asset owners, indicates there is often a lack of understanding of how this asset class works and how responsible investment practices apply in practice. Securitised products include a heterogeneous range of instruments secured by direct claims on specific assets. The vast number, variety and small size of these underlying assets help explain the challenges faced by responsible investors.

This guide is for asset owners and investment managers with less direct experience of responsible investment in the securitised space. By explaining the specific nature of securitised instruments, the guide aims to highlight the challenges but also opportunities that this asset class offers responsible investors.

Insights for this paper were collated based on:

- signatory data submitted through the Reporting Framework (256 respondents covered securitised assets in 2024);

- desk research;

- input from members of the PRI Securitised Products Advisory Committee.

We thank all participants who contributed to our research, including those on the advisory committee whom we interviewed and/or who provided feedback on our work.

The significance of the securitised market

This section reviews the size of the securitised debt market (which is on a comparable scale to the corporate investment-grade bond market) and its presence in flagship fixed income benchmarks, and therefore many bond portfolios. It also discusses opportunities for financing a more sustainable economy (arising from features of this asset class) and the growth in labelled debt.

Putting securitised debt in context

Securitised products include a heterogeneous range of instruments. They refer to bond securities created by bundling together different types of debt (including mortgages, consumer or corporate loans) and converting them into tradeable securities backed by these loans. While a corporate bond is backed by a company’s promise to pay, securitised debt is secured by direct claims on specific assets. In this paper we focus on the main categories, shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Types of securitised assets

| Securitised asset | Acronym | Collateral |

|---|---|---|

| Residential mortgage-backed securities | RMBS | Residential mortgages |

| Commercial mortgage-backed securities | CMBS | Commercial mortgages |

| Asset-backed securities | ABS | Corporate and consumer loans |

| Collateralised loan obligations | CLOs | Corporate loans |

Drivers for increased responsible investment

The adoption of responsible investment practices for securitised debt has lagged other asset classes due to challenges around data availability and the wide variety of securitisation types and structures. However there is a push for change. The PRI has identified four factors driving an increased focus on responsible investment across asset classes, including securitised debt: client demand, materiality, regulation and sustainability outcomes.

Client demand: Mainly driven by asset owners expecting increasing transparency and integration of sustainability and/or outcomes-focused strategies from their investment managers across all asset classes.

Materiality: As more data becomes available, investors are becoming better equipped to assess the materiality of sustainability factors. Market standards are also expected to continue progressing (e.g. increased adoption of industry-wide due diligence questionnaires).

Regulation: Regulatory requirements around disclosure for securitised assets specifically are few, however investors are increasingly seeking data across asset classes to improve their disclosures. Policy makers in some jurisdictions are supportive of the development of the securitised market to finance a more sustainable economy.

Sustainability outcomes: The focus on strategies that promote sustainable outcomes is growing due to, for example, the environmental/social criteria for labelled funds outlined in Article 8 and the opportunity to align with outcomes like the Sustainable Development Goals.

Significant size of the securitised industry

Securitised debt represents a significant component of the fixed income market: the total amount of securitised debt is estimated at US$14 trillion[1] globally. The bulk of the issuance is in the US fixed income market, where securitised debt represents over a quarter of the US investment-grade market, as measured by the Bloomberg US Aggregate Index.[2] The market is smaller in Europe, though still significant, with around €200 billion issued yearly[3], albeit a lower figure than before the 2008 credit crisis. Elsewhere, issuers are active on a smaller scale, in Asia for example. The scale of the market combined with the opportunity to support the financing of sustainability-themed investments make securitised debt an interesting opportunity set for responsible investors.

It is worth noting that many asset owners’ plain vanilla fixed income allocations include securitised debt due to its inclusion in flagship multi-sector fixed income benchmarks. For example, the securitised sector represents 12% of the Bloomberg Global Aggregate Index, compared to 18% for corporate bonds[4], which have received much greater attention from responsible investors. The securitised portion of the Global Aggregate Index mainly includes mortgage-backed securities issued by government-sponsored entities in the US. Further underscoring the systemic importance of this asset class, central banks (most notably the Federal Reserve) have become major holders of residential MBS as part of their quantitative easing and tightening operations.

Table 2: Market size by securitisation type (US$ billion)

| US | Europe | |

|---|---|---|

| Agency MBS | 8,990 | - |

| Non-agency RMBS | 660 | 593 |

| CMBS | 706 | 30 |

| ABS | 1,350 | 329 |

| CLO | 1,101 | 271 |

| Other | - | 43 |

Sources: Europe data: AFME (December 2024) Securitisation Data Report. US data: Morgan Stanley (February 2025)

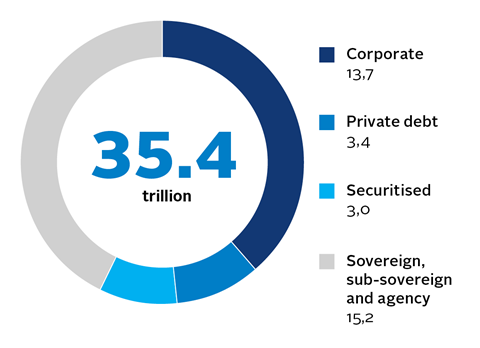

PRI 2024 reporting data shows that 9% of PRI signatories’ fixed income allocation is in securitised assets, representing US$3.04 trillion (3% of total reported assets under management). This amounts to a material component of fixed income allocations for PRI signatories.

Figure 1: Allocation to fixed income subsectors by PRI signatories (AUM US$ trillion)

Source: PRI Reporting Framework, 2024

Financing a more sustainable economy

As outlined above, the securitised debt market offers a large opportunity set for investors in the US market as well as globally. However, due to the slower uptake of responsible investment practices, securitised debt has played a minimal role in providing private capital for investments with sustainable features. Yet this asset class has features that are ideally suited to projects with positive sustainability outcomes. By bundling up smaller loans into larger tradeable securities suitable for institutional investors, the asset class provides access to capital for a large number of small borrowers. It also enables risk diversification across market participants by combining smaller funding needs into larger institutional products.

This structure can support, for example, the provision of capital to mortgages on energy efficient residential properties or loans to buy electric vehicles where, due to capital or underwriting constraints, private lending or bank finance might not be available.

The potential for securitised debt to support the low-carbon transition is gaining attention. Banque de France issued a statement in April 2024 advocating for a greater role for the use of securitisation to finance green investment in Europe. It noted that 90% of securitised issuance was in the US and that securitisation could increase banks’ capacity to finance green projects by several hundred billion euro a year. In addition, the Draghi report on the future of European competitiveness included a strong case for supporting the development of this segment in the region. A central point was that securitisation can speed up funding to the real economy and strengthen European financial stability by decreasing its reliance on the banking system.

However, in the wake of the 2008 sub-prime financial crisis, regulators and policy makers have tightened regulations around securitisation vehicles. This has slowed the growth of the securitised market but has produced enhanced transparency and underwriting standards for investors.

Securitisation and the SDGs

Securitisation can play a pivotal role in advancing the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by mobilising private capital for sustainable projects. By converting illiquid assets into tradeable securities with varying risk and return profiles, securitisation can attract a broader range of investors, increasing the flow of funds into initiatives that address clean energy, affordable housing and infrastructure development. This financial mechanism can help bridge the funding gap for projects that align with the SDGs, fostering economic growth, reducing inequalities and promoting environmental sustainability.

Thematic investing in the labelled debt market

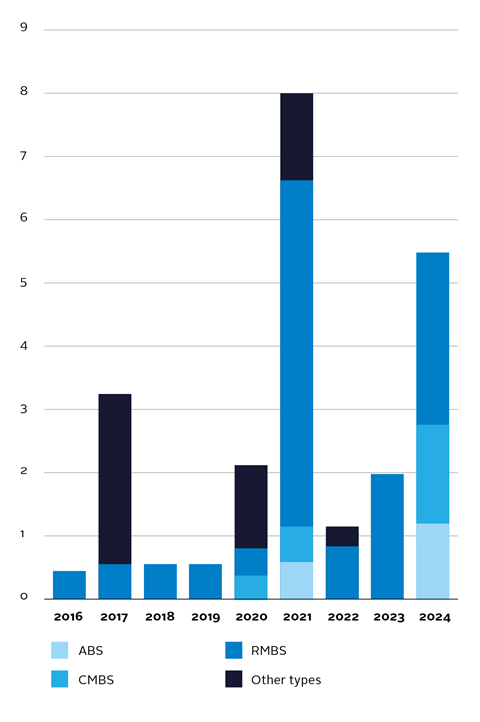

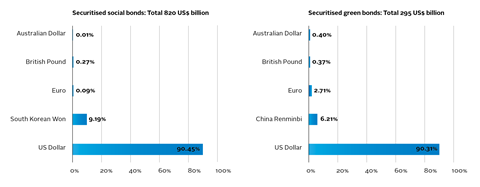

The labelled debt market, including instruments like green bonds and social bonds, has been a growing enabler for the allocation of capital to finance projects with broad sustainability characteristics. The issuance of labelled debt in the securitised market has lagged other asset classes like corporate or sovereign bonds, however it does provide an interesting opportunity to support the financing of specific sustainability developments.

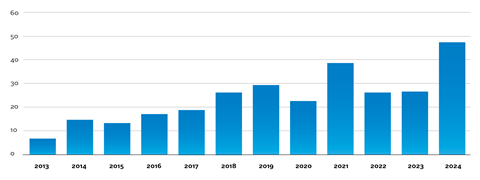

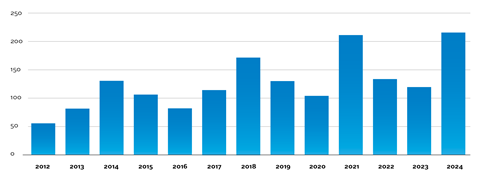

Figure 2 shows the historical issuance of labelled debt in Europe by subsegment. Figure 3 shows global green and social issuance by currency of issue.

Figure 2: Annual issuance of labelled securitised debt in Europe (EUR billion)

Source: AFME Sustainable Finance Report Q4 2024

Figure 3: Global issuance of social and green bonds by currency of issue

Source: Bloomberg, April 2025.

The securitised market offers some issuance of green, social and other sustainability-labelled debt, although on a smaller scale than in other fixed income sectors. Typically issuance follows the green, social or sustainable bond principles of the International Capital Market Association (ICMA). Notably, the June 2022 Appendix 1 update to the ICMA Green Bond Principles[5] includes a dedicated section on secured sustainable bonds, providing detailed information for green securitised issuance. However, there can also be sustainable opportunities outside of the labelled space (for example commercial mortgages with green building certifications or CLOs with specific screening criteria).

One important development in the European market has been the coming into force of the European Green Bond Standard in late 2024. It includes a separate section dedicated to securitisation and provides the first dedicated legal framework for green securitisations. This could provide an opportunity for increased issuance to meet the appetite for debt with environmental and broader sustainability objectives or outcomes. Green securitised bonds are a potential tool to mobilise institutional investor capital to finance small-scale projects like green residential mortgages, residential rooftop solar energy or small loans for energy storage projects. In the US, agencies have moved beyond green labels to create social-themed issuance: both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have published Mission Indices and begun issuing Social Single-Family MBS designed to channel capital into affordable housing and underserved communities.

Regulation

Disclosure requirements relating specifically to securitised assets have been limited, although this remains an evolving landscape. In the EU, the Securitised Regulation requires the disclosure of limited environmental performance information for some specific product types. Since 2024, while not mandatory, originators of securitised debt can choose to disclose principal adverse impacts on sustainability factors using a standardised template aligned with the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and the EU Taxonomy Regulation. This represents a positive step in promoting sustainable finance within the EU securitisation market and providing investors with the information they need to make responsible investments.

In addition, the European Green Bond standard, applicable since December 2024, creates a standardisation framework for the issuance of labelled green debt in Europe, including criteria for securitised assets. Issuance in line with this voluntary standard will be subject to reporting templates in addition to prospectus disclosure requirements, potentially increasing consistency and transparency in the market.

Incorporating responsible investment into securitised debt

Complex structures and data availability make responsible investment practices more challenging in this asset class compared to listed equities or corporate bonds. Despite the hurdles, practice has evolved on three fronts: investment analysis and decision-making; development of thematic-focused strategies; and engagement and collaboration.

In this section we have identified three areas that have seen significant evolution in practice – and offer untapped opportunities for progress: investment analysis and decision-making, development of thematic-focused strategies, engagement and collaboration.

Investment analysis and decision-making

Sustainability and governance factors are less systematically integrated in the securitised space compared to other fixed income asset classes due to a lack of data transparency and the complexity of these instruments. Investors need to be better aligned on which sustainability-related metrics are useful, although industry efforts such as standardised disclosure templates and questionnaires have been helpful. The use of exclusions and negative screens, popular in other areas of fixed income and listed equities, are typically less prevalent for mortgage- or asset-backed instruments because each instrument typically has an exposure to only one sector (such as residential mortgages or auto loans). Exclusions to other sectors/business activities are therefore irrelevant. The integration of material sustainability factors into the investment analysis to identify relevant risks and opportunities is where best practice has evolved the most.

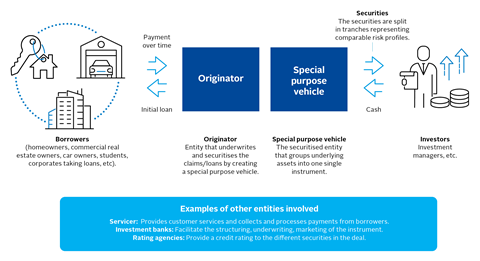

To understand why it is difficult to integrate sustainability and governance factors into decision-making or analysis in this asset class, it is important to understand the typical structure of these instruments, which:

- have multiple underlying assets: a single securitised instrument can include hundreds or thousands of individual loans;

- are made up of underlying assets that are each of a small size;

- have multiple layers between the investment manager or asset owner and the end borrower, requiring additional levels of analysis;

- may include assets from multiple geographies with different regulatory/reporting requirements.

Figure 4: Typical structure of a securitised product

On this last point, differences between the US and UK illustrate the problem. In the UK, environmental data is available for MBS through the energy performance certificate (EPC) labels, while in the US agency RMBS market it is difficult to get specific information about underlying individual mortgage loans due to data privacy protection.

We have seen changes since the PRI’s previous report on securitised debt, however, including that investors are increasingly requesting information from the various counterparties involved in the market. We have also seen increased consistency due to industry-wide questionnaires used to gather information about the underlying assets. The PRI’s 2024 reporting data showed that 81% of respondents indicated that they incorporated material sustainability factors into investment decisions in securitised debt for a majority of assets under management. The figure seems high, given the data-gathering challenges, but certainly indicates a willingness to extend responsible investment practices to this asset class.

A two-track analysis

Incorporating responsible investment considerations into the investment process for securitised instruments is complicated by the two tracks of analysis required. One is at the collateral or asset level – the assets that are being financed, e.g. a group of residential mortgages or of consumer loans. The second level is at the instrument or transaction level, including the entities involved in setting up the instrument.

Given the complexity of the analysis required to uncover sustainable risks and opportunities, best practices among investors include allocating specific resources to analyse underlying assets and the securitised instrument structure. This may be a specialised team focused on sustainability and governance issues that works very closely with the securitised analysts/portfolio managers, or an investment team that integrates a sustainability and governance focus.

Collateral or asset level

At this level, considerations include collecting sufficient information to understand the risks and opportunities relating to sustainability or governance factors which may affect the underlying assets/loans. This can be complex as information about the underlying asset is not always transparent or available. For example, an RMBS instrument may include mortgages for properties in various locations, with some prone to physical risks, but the mortgages may lack detailed location information.

If investors understand the profile of the underlying assets in a given instrument, they can identify if it is in line with the specific sustainable outcomes they are looking to finance. Examples include an agency MBS issue focused on financing social housing or a CMBS for a fully green new build. Encouraging sustainable and responsible investment practices in securitisation can be achieved by prioritising assets that contribute to positive social and/or environmental outcomes, such as renewable energy projects, affordable housing and green infrastructure.

Instrument level

The analysis at the instrument level tends to focus on the entities involved in setting it up and the overall bond documentation. Typically this involves an analysis of the originator, which is the entity that underwrote and securitised the claims/loans. The analysis would look at the types of borrowers the originator focuses on, its selection process and underwriting (lending) criteria. Replenishment criteria will also be looked at, i.e. the replacement of matured loans in the overall securitised portfolio. The practices of the servicer (if a separate entity from the originator) are also analysed. The servicer is the entity that provides customer services and collects and processes payments from borrowers. The servicers’ arrears-and-forbearance practices can also be an important component of an investor’s analysis. This instrument-level analysis is conducted together with research on the bond documentation, where investors will look at the overall structure of the securitised bond in the bond offering memorandum, noting the key counterparties in the deal, and how (in which order) bonds are paid. This is unique to securitised finance because the risk associated with the payments is divided across different bond tranches.

In the case of a CLO, the analysis would focus on the CLO manager, analysing who manages the book of loans and what loan selection criteria they use. When reviewing consumer loans packaged as ABS, the analysis focuses on governance factors relating to business practices, for example identifying cases of predatory lending which could be excluded.

For corporate bond or equity portfolios, an additional level of analysis is often done at the overall portfolio level, for example measuring carbon emissions across all holdings. In the securitised space, aggregate metrics, such as for carbon emissions, are often unavailable for a portfolio invested across several types of instruments (CMBS, RMBS, ABS and CLOs), given the heterogeneous nature of these instruments. Some tools are becoming available to understand the impact of sustainability and governance risks on the overall portfolio, for example the impact of physical climate risks on mortgage prepayment risks, but these are at an early stage of development (and often rely on assumptions and proxies). The work of the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF) aims to fill this gap by providing a consistent, sector-specific methodology for calculating and reporting financed emissions across diverse securitised portfolios. PCAF closed a consultation in early 2025 to expand its criteria to securitised asset classes. Once finalised, these standards should help investors track and manage carbon footprints at the portfolio level.

Development of thematic-focused strategies

Investment managers have started to develop sustainable versions of their securitised offerings – our interviewees mentioned for example that European asset owners are interested in separate accounts with specific sustainability angles. These types of strategies can take different forms, including:

- mindful allocation to securitised instruments that finance projects with specific environmental and/or social themes. These could be labelled instruments, such as green bonds. Best practices require investors to look beyond the label however to identify if the underlying projects are truly sustainable. For instance, there are multiple standards and certification schemes for green bonds (for example Climate Bonds Initiative), although no coordinated international standards exist yet, requiring investors to perform an analysis to understand how proceeds are used. In addition, investors can draw on external reviews – such as Second Party Opinions or verification reports from qualified providers (e.g. CICERO, Sustainalytics, Moody’s, S&P) to add independent assurance around the robustness and integrity of securitised sustainable debt instruments. As mentioned earlier, the European Green Bond Standard could have a positive impact on issuance in the region. In addition to labelled instruments, there are thematic opportunities in unlabelled instruments that finance sustainable projects or themes without necessarily carrying a green or social label – for example an ABS with a high percentage of loans for electric vehicles.

- tilting towards instruments that score better on sustainability and governance metrics, especially for investment teams that have their own proprietary assessment process.

- screening out of certain controversial activities. This is more prevalent in the CLO space, where information on the underlying loans is conducive to offering negative exclusions (e.g. no financing for companies involved in controversial weapons or thermal coal).

From an asset owner perspective, when allocating mandates to investment managers it is best practice to request reporting disclosures as part of the monitoring process. Disclosures are key to enabling the asset owner to judge whether an investment manager is meeting its responsible investment objectives and fiduciary duties, and whether it is minimising negative outcomes and maximising positive outcomes. However, the same level of reporting is not possible for securitised assets as for other asset classes, such as corporate bonds or listed equities.

Engagement and collaboration

Engagement is more challenging due to the multi-layered structure of securitised instruments, however responsible investors are continuing to engage with different parts of the ecosystem to request more data transparency.

Beyond engagement with issuers and originators, many investors are also contributing to the work of industry bodies that can influence the adoption of better standards and potentially policy setting for these market segments. The work on sustainability practices by the Structured Finance Association and the European Leveraged Finance Association are two examples. Another example is the involvement of investors in the work of the Partnerships for Carbon Accounting Financials, which is creating standards for measuring the carbon footprint in the securitised industry (more information is provided in the Resources section at the end of the report). In the labelled debt space, the ICMA brings together industry practitioners to set better standards and practices. In June 2022, it published dedicated guidance[6] for the issuance of green securitised debt, developed with extensive practitioner engagement.

Responsible investment in different securitised instrument types

MBS: Investment analysis for MBS is challenging due to personal data protection rules, however other metrics are available. Thematic investing is primarily available through US agency-sponsored labelled bonds. Engagement is facilitated by a small number of issuers in this subsegment.

ABS: The type of collateral backing the security and the counterparties involved will largely determine how best to analyse ABS. Engagement efforts focus on increasing transparency and disclosure.

CLOs: Negative screening is a popular practice in this subsegment. Sustainability questionnaires and credit rating agency reports also support analysis of CLOs.

Having laid out the basic principles responsible investors can undertake in this asset class, we now turn to how these can apply in different types of securitised instruments. The type of instrument in scope and the nature of the underlying assets will influence the lens of analysis for responsible investors.

Mortgage-backed securities

Residential mortgages (RMBS) or commercial mortgages (CMBS) have two structures: agency bonds (issued by government agencies in the US) and non-agency or private issuers. Table 3 lays out key differences between these sub-segments.

Table 3: Types of mortgage-backed securities

| Type | RMBS | CMBS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Issuer |

US agency |

Non-agency/private |

US agency |

Non-agency/private |

|

Type of loan |

Residential mortgage loans |

Residential mortgage loans |

Commercial mortgage loans |

Commercial mortgage loans |

|

Guarantees |

Guaranteed by the federal US government or originated by Government Sponsored Entities (GSEs) in the US |

Not guaranteed or originated by government or GSEs |

Guaranteed by the federal US government or originated by GSEs in the US |

Not guaranteed or originated by government or GSEs |

|

Description |

Largest market by AUM; popular with global investors; included in flagship bond indices. |

Features country-specific and borrower profiles that vary by income. |

Crucial role in financing the real estate market for over 30 years. Loans are made globally and range from trophy offices in major cities to small retail shops in rural towns. CMBS creates a financing solution for public Real Estate Investment Trusts, pension funds, insurers and private borrowers. In the US, 14% of all commercial real estate lending is financed through CMBS. |

|

|

Market size (US$ billion) |

8,990 (includes minor CMBS portion) |

1,221 |

See first RMBS column |

737 |

Sources: Europe data: AFME (December 2024); US data: Morgan Stanley (February 2025).

Investment analysis and decision-making

The analysis of MBS instruments requires different angles, given the various parties involved, and is country-dependent, given local practices and regulations.

Collateral/asset level

MBS finance hundreds or thousands of individual mortgage loans. For this reason, data transparency is challenging. In the US, personal data protection also makes agency issues less transparent. By contrast, non-agency RMBS and CMBS disclosures are generally more detailed, allowing investors to conduct more in-depth collateral-level analysis. In the US, investors can use mission indices to access enhanced disclosure for some MBS issued by Government Sponsored Entities. These indices provide additional scores on certain social criteria such as percent of loans to first-time buyers or low-income borrowers. In the UK, investors can use Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) labels, routinely available for RMBS, to focus on environmental performance. This information is also typically provided in European securitisations as part of ongoing deal reporting to investors.

Data transparency is typically better for CMBS due to lower data protection requirements. CMBS investors can often identify the specific commercial entities behind each loan in the instrument. In addition, EPC, Energy Star scores, BREEAM (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method), LEED rating (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) and other data specific to the collateral type can provide valuable insights into the environmental performance of underlying properties.

Practitioners are also starting to map out the social considerations of their investments, for example to identify pools of mortgages used to finance affordable housing.

Instrument level

When assessing sustainability and governance factors, investors typically consider the counterparties involved in originating and servicing the MBS transaction. In particular, this means analysing the originators (who made the initial mortgage loans) and the servicers (who collect monthly mortgage payments from borrowers and ultimately distribute these payments to MBS investors). Governance factors are generally considered with regards to the counterparties involved in the transaction, for example investors would examine the originator’s track record to ensure that sustainability and governance principles are enshrined in the originator’s business practices and policies.

Environmental

- Explore loans financing newly built energy- and water-efficient homes and sustainable retrofits (e.g. high-efficiency heating, ventilation, and air conditioning); also consider adoption of renewable energy in homes (e.g. solar panels).

- Assess financed greenhouse gas emissions associated with both energy and water use of underlying properties.

- Evaluate how geographic concentrations in areas exposed to physical climate risk (e.g. flood, wildfire, storms) can affect both asset values and borrower behaviours, including hazard-insurance costs and prepayment risk.

Social

- Explore loans made to underserved communities and/or to fund social and affordable housing.

- Explore mortgages which improve affordability in the housing market, e.g. low-income pools.

- Consider demographics and accelerations in social trends.

Governance

- Review originator’s business practices and policies on customer welfare; affordability checks; arrears and forbearance; management of delinquent loans.

Thematic/labelled opportunities

Labelled green MBS can provide investors with opportunities to align their portfolios with environmental goals and incentivise borrowers to invest in energy-efficient and sustainable building upgrades. Both the agency and non-agency MBS market issue labelled instruments (the agency market being the largest by volume).

Government-sponsored agency issuance: Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are prolific issuers of green bonds, issuing both green MBS bonds and green bonds not specifically backed by mortgages. For instance, in 2023 Freddie Mac issued US$1.85 billion of Single-Family Green MBS and developed a framework to issue Social MBS in 2024. Labelled MBS also include securitisations of Community Development Financial Institution loans and manufactured housing loans, expanding the supply of affordable housing.

Non-agency MBS: Although smaller by volume, private-label issuers have also brought labelled deals to market. Examples include Cascade Financial Services’ Social Bond Framework, which serves as a frame of reference for issuing social bonds.

Engagement and collaboration

Engagement, both individually and collaboratively, is a key component for investors looking to progress responsible investment practices in this market segment. Identifying whom to engage with is more straightforward in the RMBS market, where a small number of issuers represents most of the issuance. For example, most issuance is made by government-sponsored enterprises in the US and, in the UK, RMBS issuance is highly concentrated in a very few companies. Engagement mainly focuses on the availability, consistency and transparency of data. Investors typically proactively request that issuers disclose key sustainability factors when these are not specifically required by regulation, including:

- GHG emissions

- energy efficiency designations

- property size (to estimate GHG emissions)

- affordable housing designations

- impact metrics for labelled bonds – e.g. estimated annual energy savings, avoided CO2 emissions, average homeowner utility-cost reductions and number of low-income households or first-time buyers served

Collaborative engagement has the potential to help advance industry practices and standards. Organisations that securitised investors often work with on these topics include the Structured Finance Association (US). An example of industry body collaboration resulting in enhanced practices is the Structured Finance Association’s publication of ESG Best Practices for Auto ABS and RMBS Disclosures; these best practices seek to promote uniformity across data sources. Two broad categories, energy efficiency and physical risk, were identified as priority areas where RMBS issuers can adopt disclosure best practices in the short term. Even if these are voluntary, they help support the development of best practices and efficiency if issuers consistently make relevant information available.

Asset-backed securities

Asset-backed securities (ABS) are a type of securitised product backed by a diverse portfolio of loans and leases. These are typically consumer-oriented: auto loans or leases, student loans and credit card debt. In Europe, the three largest types of underlying loans in the ABS space are to small- and medium-sized enterprises, consumers and car buyers.

Table 4: European ABS issuance by collateral type

| Collateral type | Outstanding amount (EUR billion) |

|---|---|

| Small- and medium-sized enterprise loans | 108.1 |

| Consumer loans | 97.2 |

| Auto loans | 76.7 |

| Credit card loans | 25.7 |

| Leases | 8.9 |

Source: AFME (December 2024) Securitisation Data Report

Table 5: Total US ABS issuance by collateral type

| Collateral type | Outstanding amount (US$ billion) |

|---|---|

| Loans to businesses | 510 |

| Loans to individuals | 840 |

Source: Morgan Stanley (February 2025)

This wide range of types of loans offers investors a diversity of sectors to invest into, but it also makes data availability, industry practices and responsible investment practices dependent on the sector and geography. The variety in underlying loan types also gives more options in the types of themes that could be financed by ABS investors – for example lending for the purchase of electric/hybrid vehicles over internal combustion engines (ICE). As the demand for sustainable investment strategies grows, ABS that integrate transparency on sustainability and governance factors can attract a broader investor base.

Investment analysis and decision-making

Collateral level

Sustainability and governance integration practices are focused on understanding the type of collateral backing the securitisation, its environmental performance and its carbon footprint. For example, US and European securitisations in auto ABS often provide data on the breakdown of ICE vs electric vehicles for each pool. Using this type of information, it may be possible to undertake materiality mapping to identify sustainability and governance-related risks and opportunities. Social considerations are also on the rise, for instance investors assessing the socioeconomic impact from the underlying loans they are financing.

Instrument level

Investors need to consider the key transaction counterparties, in particular, the originator and servicer. For example, ABS valuations and cashflows could fall if an originator or servicer comes under the scope of environmental regulations or reputational issues. Volkswagen provides a real-life example. Through its leasing entity, Volkswagen is an originator of ABS, the value of which were impacted when Volkswagen was found to have tampered with its emissions results.

Environmental:

Auto ABS

- split of underlying loans between diesel, petrol, electric and hybrid cars as well as age of vehicles;

- emissions data for non-electric cars;

- recyclability of EVs and batteries.

Other ABS types might focus on different sustainability factors

- solar ABS: pure play green financing of residential solar panels;

- data center ABS: energy-efficient assets based on power usage effectiveness;

- fibre ABS: energy-efficient fibre infrastructure; can be sustainable if target population is underserved;

- energy use and waste management policies of borrowers generally.

Social:

- focus on underserved communities as measured by demographic data, educational outcomes (e.g. for student loans), loan terms;

- focus on consumer lending practices that view credit access as a vital social consideration; includes evaluating the interest rates and terms of loans to prevent predatory lending practices and ensuring loans are accessible to underserved communities.

Governance:

- Policies and procedures should cover customer welfare; origination and underwriting standards; quality of servicing and the use of affordability checks; arrears-and-forbearance strategy; and fair treatment of borrowers.

- Data should be available on practices such as consumer lending; affordability; debt collection; financial inclusion; flexible repayment options; and safeguards against unethical collection practices.

Thematic/labelled debt

The ABS market offers a variety of labels, sectors and underlying themes in the labelled debt space for responsible investors to pick from. In Europe, as per Figure 1, almost a quarter of labelled securitised issuance was in the ABS space. The broader opportunities and challenges described for thematic investing in securitised debt apply to this segment. One interesting recent development has been the issuance of green bonds by data centre operations. For example, two US entities, EdgeConneX Inc. and Retained Vantage Data Centers LP, issued green ABS deals in 2024 (respectively US$ 150m and US$ 525m).[7] Both transactions were backed by energy-efficient data centres. The operation of data centres is highly energy intensive and, given the rise of artificial intelligence, their electricity consumption is expected to increase. Green bonds can finance facilities with better power usage efficiency, and/or higher energy efficiency building certifications. Other types of projects typically financed with green bonds include sustainable water processes as well as renewable energy generation technologies. These types of projects show how ABS can pool small-scale sustainability assets into investable formats, expanding access to green and social finance.

Engagement and collaboration

Our interviews with practitioners highlight that the main focus of engagement in the ABS market is increasing transparency and disclosure. Investors are encouraging originators to disclose key sustainability and governance metrics pre-issuance and provide updates regularly to support informed investment decisions. Some investors engage directly with corporate issuers, which is easier in sectors such as the auto ABS segment, where auto manufacturers issue most securities.

Joining industry collaboration efforts to work on better templates and disclosure practices is important. Initiatives such as the Structured Finance Association’s ESG Best Practices for ABS Disclosures are working to address this gap. Investors are also engaging collaboratively with issuers on enhanced impact reporting. For instance, investors are pressing for granular data on auto loan emissions breakdowns or the impact metrics of social ABS frameworks (e.g. low-income borrower reach or credit access expansion).

Collateralised loan obligations

Collateralised Loan Obligations (CLOs) are backed by a diverse portfolio of loans, typically to corporate borrowers. These loans are usually leveraged loans, i.e. made to borrowers who already carry debt and/or who have a lower credit rating. CLOs are structured into tranches, or CLO notes, with different risk profiles, each of which functions as an interest-paying bond.

CLOs have played a crucial role in financing the economy for over three decades. They are particularly vital for non-investment grade companies that would struggle to secure traditional financing, often providing 50-65% of the funding for these businesses.[8]

Figure 5: Annual CLO issuance in Europe (EUR billion)

Sources: Bloomberg, PitchBook | LCD, Concept ABS, Morgan Stanley Research

Figure 6: Annual CLO issuance in the US (US$ billion)

Sources: Morgan Stanley Research, Intex

Investment analysis and decision-making

As with other securitised segments, the responsible investment analysis can be done at two levels: the underlying loans and the instrument/CLO manager level, including the analysis of the legal bond documentation. The CLO structure differs from the other sub-asset classes because its structure involves a CLO manager, responsible for selecting the underlying loans in the instrument. This role is similar to the one performed by the portfolio manager of a traditional active corporate bond fund, selecting the components of the portfolio and actively monitoring its composition. The end investor therefore will need to assess the CLO manager’s approach to sustainability as part of the instrument analysis process.

Loan level

Negative screening is a popular practice for CLOs because the underlying loans are made to specific corporate entities and it’s usually possible to map the exposure of these corporates to certain activities. This screening can be done by the end investor buying the CLO or by the CLO manager. Negative screens can include activities in industries such as tobacco or thermal coal. The analysis requires investors to look through the sector/business activities of each corporate whose loan is in the deal. Often this requires proactively requesting this information from the corporates, especially when it is necessary to understand if certain revenue thresholds are breached/complied with. S&P Global Ratings reported that, between 2018 and 2021 and looking at S&P-rated CLOs, the percentage of European CLOs disclosing sustainability-related exclusions increased from 25% to almost 100%.[9]

The CLO manager is the key organisation for setting and maintaining an exclusions list based on negative screening rules, providing transparency to end investors on specific exposures. As noted in our earlier 2021 report, as exclusions in CLOs are mainly threshold based, rather than following an absolute approach, it can be difficult to limit exposure to certain industries completely (although absolute approaches still remain relevant for areas such as controversial weapons or adult entertainment for example).

A bottom-up analysis is another common practice. If investors have access to the necessary resources and data, they can explore the exposure of the underlying companies to sustainability and governance risks and opportunities. Materiality mapping, or mapping exposures to relevant sustainability factors, can help focus the analysis on material risks. One helpful industry development has been the standardisation of information, for example industry sustainability questionnaires that facilitate borrowers sharing information with investors. Other examples include the ESG factsheets published by the European Leveraged Finance Association (ELFA), or the ESG Diligence Questionnaire published by the Loan Syndications and Trading Association in the US.

These questionnaires assist borrowers in preparing sustainability disclosures by highlighting the most material sustainability topics for a given corporate sector. As a result, new deals are now typically launched with a baseline level of sustainability and governance data, provided by borrowers through the completion of these fact sheets. These initiatives have established standards for disclosure across the loan market, enabling analysts to conduct a more thorough sustainability and governance analysis at the underlying loan level for CLOs.

Instrument level

The CLO manager (the party that selected the pool of underlying loans and structured the CLO instrument) collects the data on the underlying assets and ensures screens are applied transparently and consistently. The deal investor (the effective lender) will need to perform a level of due diligence on the CLO manager to understand its practices in selecting the loans for the CLO and engage with it to make sure all required information is disclosed.

The need for more data is a common point of engagement between investors and CLO managers. The development of documents such as the ELFA CLO ESG Questionnaire has helped meet this need. This questionnaire covers topics such as the carbon footprint at the manager level (covering scope 1, 2 and 3), TCFD reporting and diversity statistics at both the firm and investment-team levels. The questionnaire also helps to standardise expectations and encourages greater transparency around sustainability and governance practices at the CLO manager level.

Credit rating agencies also contribute to transparency by incorporating sustainability factors into their credit risk assessments for CLOs. Their analyses include the sustainability and governance risks of underlying borrowers, practices of CLO managers and the potential impact of sustainability and governance factors on credit performance.

Thematic/labelled debt

Green CLO labels are less common, however as mentioned above the incorporation of sustainability data as part of the CLOs’ selection criteria and disclosures is increasing. As the market matures, investors should be able to compare managers’ exclusion lists and scoring methodologies and get more transparency with third-party opinions.

Engagement and collaboration

Due to the multi-layered structure of CLOs, engagement typically occurs at different levels: with the CLO manager, with the underlying borrowers of loans, and broadly in the market through industry collaboration. Investors increasingly engage with CLO managers to improve transparency on loan selection criteria, sustainability practices and sustainability-related exclusions. Collaborative initiatives, such as those led by the European Leveraged Finance Association have also gained traction in recent years (see CLO Manager ESG Questionnaire example mentioned above).

Improving ESG data at the borrower level has been a key area of focus across the ecosystem. As a result, while carbon emissions data is increasingly available at the aggregated CLO portfolio level, market participants continue to face challenges in gathering and standardising other principal adverse impact (PAI) indicators.

Asset owner action

Asset owners with a responsible investment approach can consider how the securitised asset class (or rather sub-asset classes) can fit into their investment policy and investment approach and contribute to their sustainability goals. As detailed in this report, securitised assets have an important role to play in channelling capital to the real economy, including meeting the funding gap for sustainable investments. While evidence gathered from our signatories shows that asset owners evaluate their external managers in relation to how they incorporate sustainability factors in the investment process, in practice we see less focus on the securitised asset class. By getting more familiar with the subsegments of the securitised market and how they function in practice, asset owners can incorporate securitised assets into their responsible investment approach and engage with their external asset managers on this market segment.

The following list offers key actions asset owners might want to consider when allocating towards securitised debt as an asset class.

Responsible investment policy and allocation of capital:

- Consider recognising the role of securitised debt in the delivery of a responsible investment commitment or policy.

- If a responsible investment policy seeks sustainable outcomes, consider the role of labelled thematic securitised debt, which supports the allocation of capital to projects with positive sustainability benefits.

- If the fixed income allocation of the overall portfolio is exposed to broad market indices such as Bloomberg US Aggregate or Global Aggregate indices, consider responsible investment expectations for the securitised component. For example consider allocating a proactive portion of the portfolio to labelled thematic securitised debt, such as green or social MBS.

Asset manager selection, assessment and monitoring: During the selection, appointment or monitoring of investment managers, include considerations specific to securitised assets.

- Selection and assessment: Are sustainability and governance considerations integrated into the asset manager’s investment process? For instance, is a sustainability analysis performed for both the underlying loan exposure and the governance practices of originators and servicers?

- Consider responsible investment resourcing for securitised assets. Does the asset manager have a proprietary responsible investment framework for analysis?

- Does the asset manager offer thematic/environmental/social outcomes within its securitised offering?

- Monitoring: Actively encourage best practices in data transparency and reporting practices.

- Engagement: Support the development of responsible investment standards (by internal or external managers) through engagement with relevant stakeholders and collaboration.

The list of additional resources below is intended to highlight some of the most relevant sources of information for practitioners looking to learn more about debt securities and responsible investment. Practice on this issue is evolving and advancing, therefore the key resources may also evolve and other materials may become available with time.

- Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials is developing guidelines for structured products, including MBS. Equipping this market segment with standardised measures and disclosures of greenhouse gas emissions will likely increase the investor focus on adopting best practices.

- Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) is providing guidance on impact reporting and measurement, which is crucial for green MBS.

- SIFMA Uniform Practicesoutlines best practices for MBS disclosure.

- ICMA Green , Social and Sustainability Bond Principles provide voluntary guidelines on transparency and integrity in green bonds. While not specific to MBS, these principles can be a valuable reference point for green MBS issuers. The Green Bond Principles include more detailed guidance for securitised green bonds in the appendix on page 8. Also a Q&A specific to securitised labelled bonds is available in ICMA’s Guidance Handbook on page 23.

- Structured Finance Association has published ESG Disclosures for Structured Products, which provides guidance for ABS and RMBS disclosures.

- European Leveraged Loan Association’s ESG committee publishes regular resources including ESG factsheets.

- Loan Syndications and Trading Association has developed the ESG Diligence Questionnaire.

Downloads

Responsible investment in securitised debt: A technical guide

PDF, Size 1.58 mb

References

[1] Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME), Morgan Stanley

[2]Bloomberg (February 2025), US Aggregate Index

[3]Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME) (December 2024), Securitisation Data Report

[4]Bloomberg (February 2025), Global Aggregate Index

[5]ICMA Green Bond Principles (June 2021 with June 2022 Appendix 1), p.8

[6]ICMA Green Bond Principles (June 2021 with June 2022 Appendix 1), p.8

[7]Climate Bonds Initiative, Sustainable Debt Market Q3 2024 Summary, p.7

[8]Structured Finance Association (February 2020), Collateralised Loan Obligations paper

[9]S&P Global Ratings (June 9, 2022), How is European CLO Documentation Evolving to Address ESG Considerations?