The first phase of active ownership involves reviewing the investor’s overall investment strategy, including the vision, mission and investment principles of the organisation.

Active ownership as part of the overall investment strategy

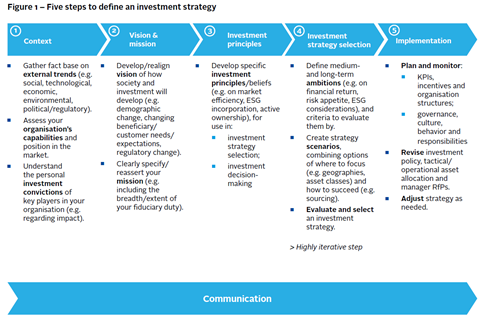

The first phase of active ownership involves reviewing the investor’s overall investment strategy, including the vision, mission and investment principles of the organisation. As outlined in the PRI’s Crafting an Investment Strategy - A Process Guidance for Asset Owners report, investors must understand the underlying trends shaping the investment environment and answer questions about their vision, mission and investment principles to define an optimal investment strategy (see figure 1 below).

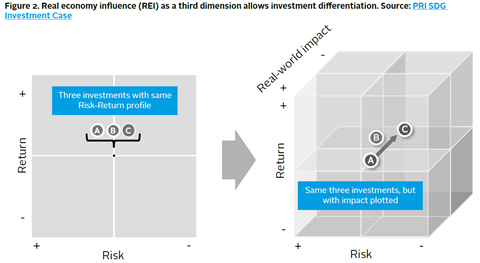

Most investors view investments on a 2D chart of risk and (financial) return. A growing number of investors integrate ESG factors with material impact to this 2D view, adjusting risk and return accordingly. However, an emerging perspective is adding a third axis which charts real economy influence (REI – the extent to which an investment positively or negatively impacts the real economy as shown in figure 2).

The active ownership policy will be highly influenced by the investor’s view on these dimensions as the objectives of engagement and proxy voting will mirror chosen priorities in terms of risks, returns and impact on the real economy.

During investment strategy formulation, investors select investment scenarios with a combination of “where to focus” (i.e. asset classes, type of funds, time horizon, industry, geographies etc.) and “how to succeed” (i.e. sourcing in-house or outsourcing, active/passive management, active ownership or not) to be tested based on external (expectations in the markets, ESG trends, etc.) and internal factors (i.e. available capacity). At the end of the process, investors will have a clear view on the type of active owners they want to be and what it requires.

Active ownership policy

Reporting Framework reference:

Listed Equity Active Ownership (LEA)

01 - Engagement policy and approach

15 - Voting policy and approach

Having developed an investment strategy, the next step is to define an investment policy.20 Investors might define their organisation’s active ownership approach directly in their investment policy. By doing so, they would signal that active ownership is not a standalone practice but a means to enhance investment decision making and execute investment objectives. Alternatively, investors could outline their approach and the relationship of active ownership with the overall investment policy in a separate responsible investment policy or engagement/voting policies. Those policies should be made available to beneficiaries, clients and the public on the organisation’s website.

Leading investors also develop expectations of companies that can be communicated either within or alongside their policies. This helps companies understand which ESG practices are highly valued by investors, the type of disclosure that can meet investors’ needs, the areas to focus on in preparation for the dialogue with shareholders, and what to expect from long-term active owners.

Policies and expectations should be reviewed periodically (i.e. annually) to reflect lessons learnt from the active ownership process, increasing and modified expectations from clients/beneficiaries, and new ESG developments. Most investors primarily develop their policies internally, but external feedback and input can be sought from beneficiaries and clients, especially in relation to ESG issues that are of concern. These policies should also receive the highest level of internal endorsement possible within the organisation’s governance structure for responsible investment (e.g. board of directors or trustees). When assets are managed internally and active ownership is carried out in-house, the investment committee should be responsible for monitoring the progress of various teams in implementing the policy.

A dedicated or integrated active ownership policy would specify some or all of the areas below:

General approach

- Alignment with stewardship principles and codes: Explanation of how the investor is aligning its approach with national or international principles and codes (i.e. the PRI, one or more national stewardship codes, the ICGN Global Stewardship Principles, etc.).

- Assets covered: Whether the policy covers the entire asset base or a specific asset class, fund or mandate; and whether engagement is conducted with companies that are currently held in the investor fs portfolios or also with those that are not.

- Expectations and objectives: Outline of the objectives for undertaking engagement and voting activities in line with the chosen investment strategy profile, including whether these activities are related and whether they are informed by, and support, investment decision making. In case of asset owners with assets managed externally and active ownership activities kept inhouse, the policy will describe how they will ensure that insights from engagement and proxy voting are shared with external managers.

- Organisational structure and resources dedicated: Explanation of who carries out engagement and voting (e.g. specialised in-house ESG teams, portfolio managers or both, etc.) and how the investor ensures that staff have appropriate capacity and experience for active ownership activities (e.g. human resources, time and training).

- Conflicts of interest: The organisation fs approach to avoiding, identifying and managing conflicts of interest, including the process to communicate potential conflicts of interest to clients or beneficiaries, and remedies to mitigate them.

Engagement

- ESG issues: Outline of key issues on which the investor wants to engage (i.e. climate change, human rights or executive compensation) and international standards it would expect the companies to comply with (i.e. United Nations Global Compact, OECD MNE guidelines etc.).

- Due diligence and monitoring process: Description of the process to monitor ESG practices and performance by investee companies to identify cases for engagement, including how information from beneficiaries, clients and other stakeholders (i.e. trade unions, NGOs and experts) will be taken into account.

- Prioritisation of engagements: Presentation of the criteria used to prioritise and select cases for engagement including how the views of beneficiaries, clients and other stakeholders will be taken into account; and whether the organisation’s engagements are primarily proactive to ensure that ESG issues are managed in a preventive manner, or reactive to address issues that may have already occurred.

- Methods of engagement: Outline of standard procedures to interact with companies (i.e. letters, emails, in-person or virtual meetings, site visits etc.) and company representatives the organisation seeks to engage with (e.g., board representatives, chairman, CEO, CSR/IR managers); and description of the general approach to collaborative engagement (i.e. selection criteria, expectations and commitment of time and resources as leading or supporting investor).

- Insider information: The organisation’s procedure for managing situations when engagers inadvertently receive non-public material information.

- Escalation strategies: Outline of the organisation fs approach in the event of unsuccessful engagement (e.g. public statement, overweight/underweight holdings, filing resolutions, voting against re-election of responsible directors, divestment, litigation etc.).

- Transparency: Explanation of how the organisation tracks and monitors engagement meetings and interactions; and a general commitment to transparency to clients/beneficiaries and the public, including type and frequency of the information (i.e. quarterly or annually).

Voting

- ESG issues: Outline of factors that will be taken into account when making voting decisions or statements on how the organisation intends to vote on specific issues (i.e. board composition, executive compensation, climate change etc); and indication of any specific corporate governance guidelines that the organisation refers to (i.e. ICGN guidelines, OECD Principles of Corporate Governance etc.).

- Decision-making processes: Description of the process to inform voting decisions, including the use of proxy voting advisors and internal research, and to monitor that votes are cast in line with the overall policy (i.e. the proxy advisor fs own policy or the investor fs bespoke policy).

- Prioritisation and scope of voting activities: Explanation of circumstances where the organisation chooses not to vote (i.e. holdings are below a certain threshold, share blocking, lack of power of attorney, etc.).

- Methods: Whether the organisation votes by proxy or in person by attending AGMs (or a combination of both).

- Regional voting practices: Explanation of how, if at all, the voting approach differs between markets and whether and how local regulatory or other requirements influence the investor fs approach to voting. Investors might publish different voting policies for different jurisdictions to take into account local codes of best practice as well as specific regulatory and listing requirements.

- Filing or co-filing resolutions: The organisation’s approach to filing/co-filing ESG resolutions and to vote on other investors’ ESG resolutions.

- Company dialogue pre or post-vote: The criteria used to prioritise communication with companies before or after votes are cast.

- Securities lending process: Outline of the approach to stock lending, and whether or where shares are recalled to vote. This might include an explanation of the reasons why the organisation has decided not to lend shares.

- Transparency: Explanation of how the organisation keeps a record of votes cast and relevant results; and general commitment to transparency to clients/ beneficiaries and the public including type and frequency of the information (i.e. pre-vote, post-vote, quarterly or annually etc.).

If an investor decides to outsource active ownership activities to specialised service providers and investment managers, the active ownership policy will contain less detail but it will still be crucial to outline the value of engagement and voting for the organisation and guide the relationship with selected third parties. In this case, the policy will describe the general approach to active ownership and specify:

Expectations: Outline of the role of third parties in implementing the organisation fs overall active ownership policy (i.e. outsourced activities are in combination with internal efforts and consider involvement of the client, or all active ownership activities are completely outsourced with no or limited involvement of the client); and a description of considerations and obligations that will be taken into account during the selection process and included in service or investment management agreements.

- Frameworks of reference: Identification of key ESG voting and engagement frameworks the organisation would like third parties to follow.

- Information requirements: Description of the level and frequency of information the organisation expects to receive to periodically monitor their performance and potentially use the information for financial decisionmaking purposes.

- Monitoring: Description of how external third parties will be monitored (i.e. questionnaires, analysis of information, periodic meetings etc.), including how the investors will ensure that votes are cast in line with the chosen voting policy (i.e. tailored or provided by the service provider/investment manager).

Existing active ownership policies range from those that are very detailed, covering most items that would be considered at AGMs or during engagement dialogue, to more general documents defining a broader framework of reference for engagement and voting activities. While with the former investors can communicate clearly their expectations to companies, with the latter, investors retain a higher degree of flexibility on how to engage and vote. In any case, the possibility of applying discretion is usually key for institutional investors that need to consider their members’/clients’ best financial interests.

Conflicts of interest

Investors should pay particular attention to possible conflicts of interest when conducting active ownership activities. Conflicts can arise when investment managers have business relations with the same companies they engage with or whose AGMs they have to cast their votes at. A company that is selected for engagement or voting might also be related to a parent company or subsidiary of the investor. Conflicts can occur when the interests of clients or beneficiaries also diverge from each other. Finally, employees might be linked personally or professionally to a company whose securities are submitted to vote or included in the investor’s engagement programme. The disclosure of actual, potential or perceived conflicts is best practice. Equally, detailed processes for managing these conflicts should be publicly disclosed so that clients can always understand how proxies at issuers that are also clients have been cast. Such procedures serve to protect an organisation’s brand and reputation and may help to insulate it from consequences, such as penalties and litigation.

Leading practices for managing conflicts of interest include:

- specifying in the active ownership policy that engagement processes and voting rights are exercised in line with the best interest of clients to protect and enhance the long-term value of shareholdings;

- adopting an oversight structure with regional or global committees reviewing voting decisions and engagement activities on a regular basis;

- comprehensively mapping potential conflicts of interest and corresponding means of mitigation and periodically reviewing these;

- allowing for any unforeseen conflicts of interest to follow an escalation procedure involving top management (CIO, CEO, compliance officer, etc.);

- reporting any incidents and potential conflicts in a database that is accessible to clients;

- creating Chinese walls or setting different reporting lines between entities responsible for active ownership activities and other entities providing consulting and investment management services to corporate clients, or having sales responsibilities to ensure neutrality and independency;

- developing a code of conduct for engagers/voting analysts and ensuring that employees declare any other professional activity to the compliance department;

- a recusal on votes at entities and independent fiduciaries where significant pecuniary interests exist by delegating the decision making for such votes to a nonconflicted independent third party; and

- making provisions on how external service providers and investment managers need to treat conflicts in contracts and investment agreements.

Share lending

Reporting Framework reference:

Listed Equity Active Ownership (LEA)

19: Securities lending programme

Share lending is the temporary transfer of shares by a lender to a borrower, with agreement by the borrower to return equivalent shares to the lender at an agreed time and pay lending fees. This process usually involves an intermediary organisation. Therefore, the relationship between lender and borrower is often not direct. When shares are lent, voting rights are passed to the borrower, unless the lender recalls the shares. Due to this transfer of shareholder rights and consequent disconnect with investment decisions, some investors might decide to not have a share lending programme at all or establish a maximum threshold of shares that can be lent so that a minimum level of voting is guaranteed. Similarly, it is good practice for investors to officially commit to not borrowing shares for the purpose of exercising voting rights.

When investors keep or initiate share lending practices, important considerations have to be made to define when recalling shares for voting purposes. Recalling all shares is usually a rare approach as this could cause clients or beneficiaries to incur financial losses greater than the negative impacts of not exercising voting rights (for example, when there are no controversial items on the agenda). Nevertheless, some investors have included this as a condition in custodian contracts.

- The most common criteria to recall shares are prioritising:

- shares in domestic markets;

- significant holdings;

- controversial votes and high-profile meetings on ESG issues;

- votes on M&A and important financial transactions;

- shares of companies targeted by an engagement programme; and

- cases when the vote might be material and influence the long-term performance of a company based on a cost-benefit analysis.

The ICGN Securities Lending Code of Best Practice is an additional source of guidance for investors interested in initiating a share lending programme that does not impede responsible voting activities.

| ORGANISATION | APPROACH |

|---|---|

| AP2, Asset Owner, Sweden | AP2 lends Swedish equities in exceptional cases, and never more than 90% of its holdings in an individual Swedish or foreign company. Where Swedish equities are loaned, they are recalled prior to the AGM. AP2 places a ceiling on the maximum value of such lending. |

| BlackRock, Investment Manager, US | BlackRock’s approach is driven by its clients’ economic interests. The evaluation of the economic desirability of recalling share loans involves balancing the revenue-producing value of loans against the likely economic value of casting votes. It believes that, generally, the likely economic value of casting most votes is less than the securities lending income, either because the votes will not have significant economic consequences or because the outcome of the vote would not be affected by BlackRock recalling loaned securities to ensure they are voted. In addition, BlackRock may in its discretion determine that the value to clients of voting outweighs the cost of lost revenue to them from recalling shares, and thus recall shares to vote in that instance. |

| BNP Paribas Asset Management, Investment Manager, France | BNP Paribas Asset Management monitors the number of shares on loan before a vote. When it considers that too many securities are on loan, or when the vote is important for the company, it instructs to recall lent stock or to restrict stock lending to vote on the majority of its position (around 90%). Because of recent regulation on stock lending matters, it rarely has a significant proportion of stock on loan near a general meeting. It does not lend shares in SRI portfolios. |

| British Colombia Investment Management, Investment Manager, Canada | All shares are recalled for voting unless there are unusual circumstances, which is embedded in custodian contracts. Shares can be lent out but must be able to be recalled by record date. Custodians are required to recall every share for voting and they must report on any exceptions. |

| PGGM, Investment Manager, Netherlands | PGGM does not lend shares of an internal list of companies that: are part of the largest holdings; are involved in its engagement programmes; and/or present crucial decisions to be voted on. It also never lends more than 90% of shares. |

| State Street Global Advisors, Investment Manager, US | For funds where SSGA acts as trustee, the firm may recall securities in instances where it believes that a particular vote will have a material impact on the fund(s). Several factors shape this process. First, SSGA must receive notice of the vote in time to recall the shares on or before the record date. In many cases, SSGA does not receive timely notice and is unable to recall the shares on or before the record date. Second, SSGA, exercising its discretion, may recall shares if it believes the benefit of voting shares will outweigh the foregone lending income. This determination requires SSGA, with the information available at the time, to form judgments about events or outcomes that are difficult to quantify. |

| UniSuper, Asset Owner, Australia | UniSuper recalls all domestic stock for voting and its custodians have instructions to do so. Internationally, recalling is a cost/benefit issue (also bearing in mind the complexity of recalling stock in different markets). It would try to recall stock if there was an issue identified as critical, but this has not yet happened. |

| Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS), Asset Owner, UK | USS undertakes a process that brings together meeting information and holding positions in one spreadsheet to enable final decisions on stock recalls to be made. Where USS owns more than 3% of the company, it will always recall the shares and vote the full position at a meeting. When it holds between 0.5% and 3% of issued share capital in the company, a discussion will be had in consultation with the portfolio manager to decide if there is a material need to restrict the stock. For EGMs, it decides on an ad-hoc basis, taking into account commercial interests. USS believes there is no economic reason for recalling all shares where the issues at an AGM are routine and/or non-controversial. |

Download the full report

-

A practical guide to active ownership in listed equity

February 2018

A practical guide to active ownership in listed equity

- 1

- 2

- 3

Currently reading

Developing an active ownership policy

- 4

- 5

- 6