Module III - Investment process

Integration of ESG factors into portfolio construction, investment process and stewardship practices may be driven by client values, regulation or evidence that ESG factors are correlated to security performance and financial returns (see Module I). However, there is a significant difference in the integration of RI at the hedge fund strategy level between, for example, equity long/short, FX, volatility or statistical arbitrage strategies. These differences in ESG integration and stewardship practices need to be recognised by the asset owner and investment manager and will inevitably require different approaches.

Identify ESG factors

This section covers ESG integration within a selection of asset classes - outlining some key issues surrounding specific asset classes or financial instruments - and is by no means a conclusive list. This section does not look to repeat guidelines or work outlined in other PRI publications, but to provide select specific examples. Investment managers may want to review the appropriate approach as outlined by other PRI work:

Equities

The CFA Institute and PRI have developed an ESG integration framework for equity investing. The framework outlines three separate levels of integration of ESG issues into an investment process:

- Investment research;

- Security valuation; and

- Portfolio construction

This framework was designed for equity investors but it provides a useful reference point for hedge fund professionals as they develop ESG-integrated investment processes across a range of asset classes.

Different types of investment strategies (Event Driven, Credit, Systematic, Activism etc.) will have different approaches where elements of this framework will be more relevant. As hedge funds have a broad remit to invest in a range of asset classes, the relevance will depend on the asset class, financial instruments5, portfolio mandate and time horizon.

Different types of investment strategies (Event Driven, Credit, Systematic, Activism etc.) will have different approaches where elements of this framework will be more relevant. As hedge funds have a broad remit to invest in a range of asset classes, the relevance will depend on the asset class, financial instruments5, portfolio mandate and time horizon.

As an example, a fundamental difference between certain hedge fund strategies and long-only equity investment strategies is that hedge funds have the option to take long and short positions in equities (and other asset classes). This provides the opportunity to consider material ESG factors separately for long and short positions. These positions might reflect different corporate approaches to material ESG factors and be identified using frameworks such as the SASB materiality matrix (SASB).

The SASB materiality matrix provides an insight at issuer or security level, but the portfolio-level materiality of an issue might be determined by a broader range of factors such as:

- Portfolio turnover

- Investment strategy

- Time horizon

- Position size (relative and absolute)

Fixed income

The integration of ESG factors into fixed income varies depending on the asset classes and financial instruments. This section outlines some issues relating to distressed corporate bonds and sovereign debt.

Distressed corporate bonds

Some investment strategies may take positions in distressed corporate bonds. These may have lower levels of liquidity or be special situations where positions are held for longer periods with higher levels of control. These types of businesses may have lower ESG scores and the investment manager may have a stronger position to influence management strategy to improve ESG performance through engagement with management teams. This approach may also be taken by event driven equity managers with a similar rationale.

Sovereign debt

The PRI has published a guide on the integration of ESG into sovereign debt market. This outlines different ESG factors that are relevant to these markets.

- Governance has traditionally been regarded as the most material ESG factor for sovereign debt and has been extensively incorporated into credit rating models and valuations. Investors can seek measures of a country’s political stability, government and regulatory effectiveness, institutional strength, levels of corruption and the rule of law.

- Social factors can also be material in sovereign credit analysis due to the importance of human capital as a key determinant of economic growth. Measures of demographic change, education, living standards, income inequality and social cohesion can inform sovereign bond valuations.

- Environmental factors have typically been less analysed by sovereign debt investors, though this is changing as the physical and economic impacts of climate change and resource constraints become more evident. Investors are increasingly considering measures of natural resource availability, climate related and energy transition risk.

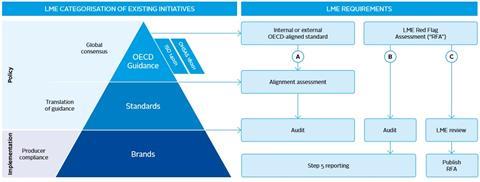

Figure 15: Responsible sourcing and the London Metals Exchange

The LME has launched a consultation on the proposed introduction of responsible sourcing standards across all LMElisted brands. These rules would implement standards which are consistent with, or build upon, the OECD Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas, using the following framework:

The most suitable approach to integrating ESG factors into the selection and ownership of commodities will clearly involve a rigorous focus on the supply chain and the promotion of better practice in the production, extraction and processing of all types of commodities.

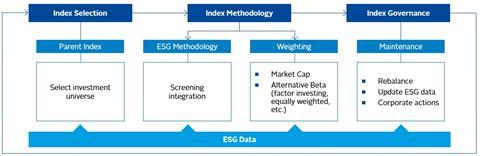

Security indices

Financial instruments investing in security indices are utilised in some hedge fund strategies. Though liquidity remains an issue, the growing numbers of ESG indices provide hedge funds with an opportunity to invest in instruments that attempt to capture ESG trends or criteria. These benchmarks may also be suitable to measure relative performance.

Figure 16: Structure of ESG indices

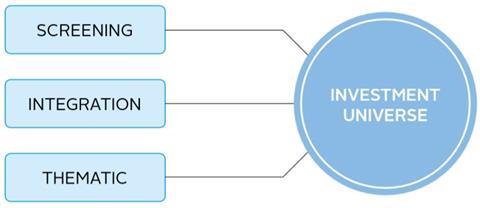

Define investment universe

Defining an investment universe is a function of the portfolio mandate. It might involve processes such as a screening to reflect beneficiary values, integration of ESG into investment decision making or a thematic approach to building a portfolio. In all processes, incorporation of ESG factors should co-exist and complement existing processes.

Figure 17: Define an investment universe

Build a portfolio and asset allocation

There are a broad range of approaches to incorporate ESG factors into portfolio construction. For example, some ESG mandates have an unconstrained universe and introduce quantitative tilts towards securities or issuers with certain ESG scores or upward trends. Others may require restrictions on positions (long and short) of securities or issuers involved in certain activities such as weapons manufacturing.

Asset allocation decisions play a fundamental role in determining long-term portfolio returns. Multi-asset hedge funds might want to incorporate long-term issues, such as climate change, demographics and resource depletion, into asset allocations decisions. The PRI has recently completed a discussion paper on strategic asset allocation (SAA). The paper argues that SAA should be an obvious place to start reviewing and integrating ESG themes and issues into asset allocation decisions. It outlines three steps in integrating ESG into the SAA process.

Figure 18: Embedding ESG into asset allocation decision

Active ownership (or Stewardship)

Active ownership can be broadly defined as the use of investors’ collective influence over investees, policymakers and other stakeholders to deliver real-world outcomes that ensure the long-term sustainability of investment markets and the broader economy. PRI signatories agree to Principle 2, which states “We will be active owners and incorporate ESG issues into our ownership policies and practices”.

For equity and fixed income investors this approach can include engaging with securities or policy makers to promote better practice either through informal or formal processes. Formal engagement activities might include proxy voting, shareholder resolutions, divestment and policy engagement. These approaches might complement informal management engagement.

Figure 19: Active ownership approaches for HF managers

Many of these processes are shared between long only and hedge fund managers. However, hedge fund managers may encounter some specific issues when implementing Principle 2. For example, systematic managers who construct diverse portfolios may not have the resources to be able to engage directly with company management due to rapid portfolio turnover or short holding periods.

Divestment

When formal or informal engagement towards a set objective is failing, hedge fund managers may consider a range of escalation strategies including public statements, filing resolutions, voting against re-election of responsible directors and, ultimately, divestment. Divestment is considered by an increasing number of asset owners as a possible mechanism to escalate an engagement process. As an alternative to divestment, hedge fund managers may also take short positions on issuers or securities where engagement has not been successful.

Stock lending

For asset owners, stock lending raises challenges. Stock lending is a process that enables hedge funds to construct hedging, arbitrage, or short selling positions. It is the temporary transfer of shares by an investor to a borrower in exchange for a fee, with agreement by the borrower to return equivalent shares to the lender at an agreed time. When shares are lent, voting rights are passed to the borrower and the underlying owner may recall the shares to undertake proxy voting.

In December 2019, Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF) suspended the practice of stock lending. The rationale for suspending the practice was that stock lending results in a temporary transfer of ownership rights to the borrower. GPIF held the view that stock lending creates an inconsistency with their asset managers’ abilities to fulfil their stewardship responsibilities over the underlying investments. Other investment managers have adopted a range of approaches which are outlined in PRI’s Practical Guide to Active Ownership in Listed Equity.

The ICGN Securities Lending Code of Best Practice is an additional source of guidance for investors interested in initiating a share lending programme that does not impede responsible voting activities. Hedge funds should ensure that stock is returned in a timely manner when required for voting.

Shorting

For hedge funds, short selling is a trading strategy employed when they believe that a financial instrument is overpriced. It generally means borrowing a financial instrument (e.g. equity, commodity futures contract) and selling it, with the understanding that it must later be bought back (hopefully at a lower price) and returned to the party from which it was borrowed. There are a range of questions around the relationship between ESG and short selling. Short selling is one way for a hedge fund manager to express the view that an entity is not adequately incorporating ESG factors.

Module IV - monitoring and reporting

The PRI’s Principle 6 calls for signatories, including hedge funds, to ‘each report on our activities and progress towards implementing the Principles.’

This could include topics such as:

- How ESG issues are integrated within investment practices;

- Disclosure of active ownership activities (proxy voting and policy or corporate engagement); and

- Public reporting on the impact of active ownership activities and investment practices.

Reporting may be particularly useful to asset owners when it follows these principles:

- Timely and recurring – reporting might follow a similar schedule to performance or mandatory reporting;

- Consistent and comparable – enabling asset owners to track change and improvement and compare against hedge funds following similar investment strategies;

- Incorporates real world impact – so that asset owners can measure the impact of an ESG policy on real world outcomes (See PRI Active Ownership 2.0)

Hedge fund managers might want to adapt their specific approach to ESG reporting to reflect:

- Long/short exposures - for example an approach might be to report net long exposure to enable measurement or comparison of a portfolio against ESG metrics.

- Relative to benchmark – due to differences in benchmark selection, certain hedge fund strategies may find it difficult to select an appropriate benchmark to compare ESG performance e.g. on their carbon footprint. These funds might rely on improvement year on year rather than a comparison with a specific benchmark.

- Risk monitoring – for ex-post analysis, suitable tools might enable risk monitoring to measure net exposure to securities with specific ESG characteristics.

- Impact measurement – some institutional clients may require managers to report on the impact of their portfolio. This might be through case studies or quantitative approaches such as carbon footprinting and the EU Taxonomy.

References

5 Structured products and derivatives are out of scope of this guide. PRI will publish guidelines on these specific topics.