How real assets investors can apply the recommendations of the Taskforce for Climate-related Financial Disclosures

Overview

The guide sets out different actions for real assets investors to implement the TCFD recommendations. It considers steps that both direct investors in real assets, and those investing through external managers, may take during the typical investment cycle for real assets. These processes and actions may need to be built up over time, depending on the stage each investor is at on its TCFD implementation journey.

What are the key drivers?

Climate change is increasingly material for all investors, including those in real assets. Real assets, whether properties, infrastructure assets or forestry and farmland, face a range of impacts from the physical effects of climate change, and from regulatory actions designed to reduce emissions and influence consumer behaviour. Moreover, real assets investors, whether asset owners or investment managers, increasingly face client and public pressure to take a systematic approach to address climate risk and communicate it effectively.

What are the priority actions for real assets investors?

The guide addresses each element of the TCFD’s four-pillar framework in turn, and outlines a series of priorities for each, as illustrated below. Real assets investors’ progress so far in implementing the TCFD’s recommendations is strong in some areas – more than four in five report on climate risks and opportunities – but more work is required in others. There is limited take-up of actions under the ‘Metrics and Targets’ pillar in particular, as shown in Figure 1. This area was the principal focus of our interviews and workshops during the research phase of the project.

Figure 1: Percentage of real assets investors reporting against the TCFD recommendations. Source: PRI reporting data 2020

Governance

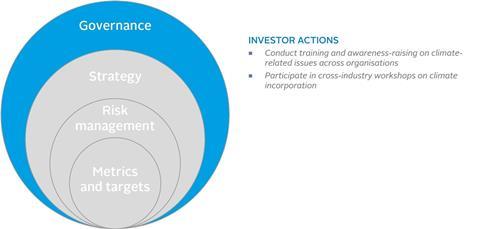

- Raise climate awareness throughout the organisation

- Conduct training and awareness-raising across organisation on climate change

- Participate in cross-industry initiatives on climate incorporation

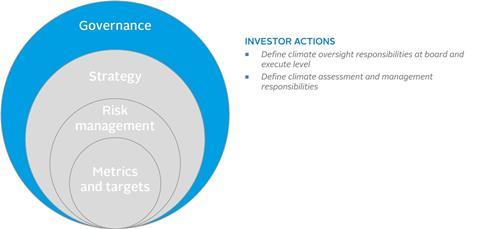

- Develop a governance system to manage climate related risks

- Define climate oversight responsibilities at board and executive level

- Define assessment and management responsibilities for climate-related issues in strategy-building and investment process

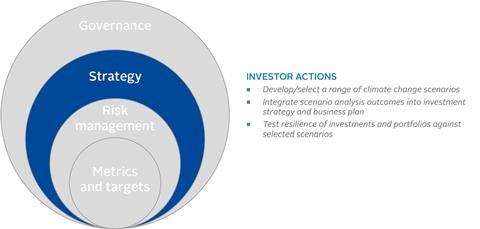

Strategy

- Develop a strategy for identifying and addressing climate risks and opportunities

- Develop/select a range of climate change scenarios (qualitative and/or quantitative)

- Integrate scenario analysis outcomes into investment strategy and business plan

- Test resilience of investments and portfolios to selected scenarios

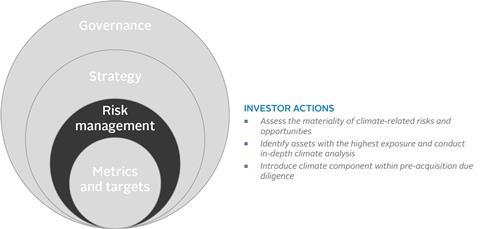

Risk Management

- Fully integrate climate risks and opportunities into investment processes

- Assess the materiality of climate-related impacts and opportunities using sector and scenario analysis

- Introduce climate component within pre-acquisition due diligence, and in vendor reports prior to exit

- Identify assets with the highest exposure and conduct in-depth climate analysis

- Define and support implementation of action plan to strengthen climate resilience at asset level

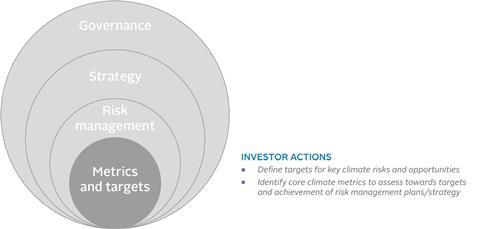

Metrics and targets

- Define clear climate targets and select key metrics used to monitor progress towards those objectives on a regular basis.

- Define targets for key climate risks and opportunities

- Identify core climate metrics to assess progress towards targets, the achievement of risk management plans, and the success of the overall strategy

| TCFD pillar | PRI reporting item[1] | Practical Steps | Deliverables |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Governance |

|

|

|

|

Investment and Stewardship Policy (ISP) reporting item 28 ISP 29 |

|

|

|

|

Strategy |

ISP 30 ISP 30.1 ISP 31 ISP 32 ISP 33 ISP 33.1 |

|

|

|

Risk Management |

ISP 34 ISP 35 ISP 36 |

|

|

|

Metrics and Targets |

ISP 37.1 ISP 38 ISP 38.1 ISP 39 ISP 39.1 |

|

|

The guide also highlights practical resources that are available to support real assets investors in implementing these four pillars of the TCFD recommendations, as well as examples of how some investors have approached different elements highlighted above.

Background

The Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD)

The TCFD was established in 2015 by the Financial Stability Board, a body set up by the G20, to develop a set of voluntary, consistent disclosure recommendations for companies to use when providing information about their climate-related financial risks. This information is designed to focus on the aspects of climate change that are material for financial stakeholders.

The TCFD’s objective is to provide a systematic framework for investors to address climate-related risks and opportunities in their investment processes.

However, the TCFD does not impose specific methodologies on how to address climate risk. An investor’s climate policies and practices cannot therefore be said to be ‘compliant’ or ‘in line’ with TCFD recommendations. Rather, an investor can report on its progress in implementing a climate related management approach in line with the TCFD’s recommended disclosures.

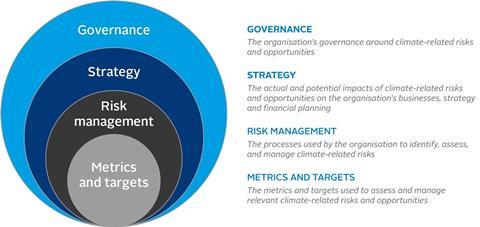

The TCFD recommendations are articulated around four pillars: governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics and targets.

Figure 2: Core elements of recommended climate-related financial disclosures. Source: TCFD

The TCFD can be a useful tool to build familiarity with some key climate-related concepts, such as the typology of risks and metrics for assessing climate exposure.

The key definitions are:

- Physical risks resulting from climate change:

- Acute risks: event-driven exposures, including the increased severity of extreme weather events (cyclones, hurricanes, floods, etc.); and

- Chronic risks: longer-term shifts in climate patterns (e.g., sustained higher temperatures) that may cause sea-level rise or chronic heat waves, for example.

- Transition risks resulting from the transition to a lower-carbon economy:

- Policy and legal risks: the evolution of regulations and potential litigation or legal risk;

- Technology risks: technological improvements or innovations that support the transition to a lower-carbon, energy-efficient economic system;

- Market risks: the effects of climate change on supply and demand; and

- Reputation risks: changing customer or community perceptions related to climate considerations.

The key concepts include:

- Materiality analysis: assessing the exposure of investments or assets to climate-related risks in order to focus on those facing the highest risks.

- Scenario analysis: evaluation of an asset’s economic and strategic resilience under different climate scenarios. Scenario analysis can be used to assess whether and how an asset will be affected by physical and transition risks, depending on different climate trajectories.

- Carbon footprint: measuring the carbon emissions of an organisation related to its activities.

- 2°C alignment: aligning investments with international climate goals and the aim of the Paris Agreement to hold warming to below 2°C above pre-industrial levels.

- Just transition: assessing the impact of job losses and industry phase-out on workers and communities, and considering how to produce new, green and decent jobs, sustainable industries and healthy societies.

Drivers

Materiality

Climate change impacts can materialise in several ways for real assets investors. For example, the growing frequency and severity of extreme weather events have left assets in certain geographies increasingly exposed to the physical impacts of climate change, such as sea-level rise or extreme heat. Transition risks, particularly through changing market regulation and policy, are having and will continue to have a material impact on real assets.

Investors must assess their exposure to both physical and transition risks, and consider how to embed this assessment into their investment processes.

Climate change can have a range of impacts on real assets, creating risks and opportunities.

- Impact of sea level rise on real estate value in the US. Flooding caused by sea level rise has had an impact on the value of real estate holdings in coastal areas of the United States. First Street Foundation, a non-profit organisation specialised in modelling US flood risk, estimates that from 2005 to 2017, such flooding led to a $7.4 billion fall in home values across five coastal states. Florida was the most affected state, with the losses reaching an estimated $5.42 billion.

- Stranded assets. Transition risk can materialise through assets losing value prematurely as a consequence of the transition to a low-carbon economy. Insurance company Euler Hermes estimates that between 1997 and 2017 the value of energy sector assets in the US depreciated by approximately USD 1.4 trillion. Oil and gas assets account for the majority of the loss in value, but estimated losses in the utilities and construction sectors also both exceeded USD 340 billion.

- Investments to support the low-carbon transition. The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) has said in its Global Landscape of Renewable Energy Finance 2020 report that investments into renewables must reach ‘USD 800 billion per year by 2050 to fulfil key global decarbonisation and climate goals’. The PRI’s Inevitable Policy Response project further highlights a market value potential of US$7.7 trillion for Nature Based Solutions, measured as the net present value of carbon stocks generated between now and 2050. This would include huge new investments in forestry, for example.

Regulatory Changes

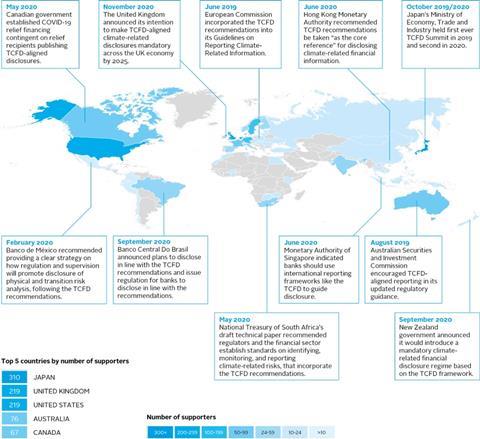

The TCFD was initially established to encourage organisations to submit voluntary climate-related disclosures. However, in 2020, New Zealand became the first country to introduce mandatory disclosure against the TCFD recommendations for organisations across the financial system.

More countries around the world are likely to follow suit in the years ahead. The map below shows selected jurisdictions where governments and regulatory bodies have taken action in relation to the TCFD, highlighting how broad the uptake of the TCFD has been across the globe.

Figure 3: TCFD developments around the world. Source: PRI

Client and public demand

Client and public pressure for investors to act on climate change is also growing. Not taking action is likely to increase brand and reputational risks, and may also result in lower liquidity or lower the attractiveness of assets to prospective buyers.

Real assets investors, whether investing directly or indirectly through managers, therefore face pressure to ensure their approach to assessing climate-related risks is practical, and properly aligned with their overall investment strategy. Asset owners, for example, are increasingly asking about climate action in their due diligence and manager evaluations. However, many asset owners lack formal methods to assess managers’ approaches to climate change. In general, managers would also prefer a harmonised approach from asset owners, with consensus on the datapoints needed to support the assessment of a manager’s approach to climate change.

The New York State Common Retirement Fund systematically reviews how infrastructure managers integrate climate considerations into their investment processes. Each phase of the investment process is assessed, from sourcing to exit, to understand how managers are thinking about both transition and physical risks and opportunities at the asset, portfolio, operating company and parent company levels. The Fund incorporates the TCFD framework into the climate category of its Real Assets ESG scorecard for new investments, and has also developed a climate toolkit for its internal Real Assets investment team that is shared with its managers and investment consultants. In addition, the Fund uses GRESB7 data as part of its due diligence and manager monitoring programme. Given the Fund’s recent announcement of a Net Zero carbon emissions target, to be achieved by 20408, these efforts to drive greater adoption of climate integration best practices across its manager base will be intensified in the years ahead.

Consistent disclosure and climate data

When combined, all three key drivers highlighted above should lead to more consistent climate disclosures by real assets investors, and ultimately support the development of more in-depth and widely available climate data sets. Better data sets will in turn allow the implementation of more consistent climate metrics and targets, and allow for greater transparency on individual investors’ (and their assets’) climate performance. On the other hand, the current lack of such data is widely cited as an obstacle to action by a large number of real assets investors.

Implementing the TCFD recommendations

| TCFD pillar | PRI reporting item[1] | Practical Steps | Deliverables |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Governance |

|

|

|

|

Investment and Stewardship Policy (ISP) reporting item 28 ISP 29 |

|

|

|

|

Strategy |

ISP 30 ISP 30.1 ISP 31 ISP 32 ISP 33 ISP 33.1 |

|

|

|

Risk Management |

ISP 34 ISP 35 ISP 36 |

|

|

|

Metrics and Targets |

ISP 37.1 ISP 38 ISP 38.1 ISP 39 ISP 39.1 |

|

|

Pillar 1: Governance

The first pillar of the TCFD’s recommended disclosures relates to an organisation’s governance of climate-related risks and opportunities. As such, organisations should disclose the roles of governing and managing bodies (e.g., by defining climate-related responsibilities, describing the role and meeting frequency of climate-related committees, and monitoring the progress of the climate strategy).

In order to support the implementation of the TCFD recommendations in the investment process,real assets investors should assess whether they have the relevant governance and strategic measures in place at the firm level. As part of this, it is essential to ensure formal commitment from senior executives to guarantee sustained institutional dedication and resources.

PRI resources such as Implementing the Taskforce for Climate-related Financial Disclosures: A Guide for Asset Owners and Integrating ESG In Private Equity, A Guide for General Partners describe different actions that both asset owners and investment managers can take to support integration of climate risks and opportunities, and also ESG factors more broadly. For most organisations, climate related processes will follow closely, or be fully integrated into, their overall ESG strategy rather than requiring the development of standalone practices or governance structures.

Training and awareness raising

A first step towards addressing climate change often consists of raising awareness and developing resources and knowledge within teams internally. This is particularly important to ensure that consideration of climate-related issues is not seen solely as the responsibility of an ESG/ responsible investment team, but rather something that all parts of an organisation must address.

Given the pace of developments on climate-related issues – regulatory and/or legislative developments, evolution in the concept of fiduciary responsibility in different jurisdictions, greater data and information availability on climate-related impacts and longer-term trends, and so on – organisations should also ensure that training and climate awareness are updated and repeated on an ongoing basis.

Many investors have developed internal training programmes, sometimes with the support of external partners, particularly with the objective of helping investment teams to gradually integrate climate-related issues into their analyses. Exercises such as mock climate due diligence exercises, or using examples of how climate risks have materialised and impacted financial performance, strengthen these organisations’ own climate knowledge and help them gain autonomy during the climate risk assessment phase of their investment processes.

Introduced in 2016, Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan’s (OTPP’s) climate change working group (CCWG) is a collaborative team, comprised of representatives from across the organisation’s investment divisions. It is chaired by the Managing Director of one of the investment teams and facilitated by the Responsible Investing team.

The group convenes monthly to discuss climate change related topics affecting the organisation as a whole, as well as at the asset class-level. This helps to ensure that investment professionals have sufficient knowledge of climate change and its impact on the pension fund and their respective divisions.

The CCWG plays a key role in informing OTPP’s climate change strategy and its transition to a low carbon economy. By collecting the inputs of investment professionals across asset groups, the fund is able to incorporate asset class-specific considerations into its broader climate plan. This makes the strategy more comprehensive and builds buy-in at the asset class level.

The CCWG also helps build climate awareness across the organisation, promoting a two-way communication channel: CCWG’s meetings focus on knowledge sharing and also include an educational component, sometimes with the support of external experts. This information is then distributed to the members’ respective asset class teams. At the same time, the CCWG’s participants raise discussion points from their asset group (e.g., the Infrastructure and Natural Resources group), providing communication back to all CCWG members, spurring dialogue and knowledge transfer.

Some of the initiatives led by the CCWG include climate scenario analysis, physical risk assessment at the fund level, and the study of metrics and indices, among others. The group was also fundamental in creating the foundation for OTPP’s commitment to net zero emissions by 2050, and is currently working to develop interim carbon targets.

Collaboration

There are an increasing number of initiatives across all parts of the real assets industry that seek to drive collaboration between investors and other stakeholders. Their purpose is to share best practices, raise awareness on climate change issues, and encourage stronger action. These initiatives can also be a source of tools and support for investors, as they develop their climate strategies.

Infrastructure – The Coalition for Climate Resilient Investment (CCRI): This initiative aims to increase the resilience of infrastructure investments and the broader financial industry by seeking to develop the accurate pricing of physical climate risks in the investment process. The coalition is supported by actors from both the public and private sectors, including institutional investors and governments.

Real estate – The Net Zero Carbon Buildings Commitment: This initiative was launched by the World Green Building Council (WorldGBC) and aims to push for net zero carbon buildings around the world. By formalising their participation, businesses commit to having all their assets reach net zero carbon in operation by 2030, as well as advocating for net zero carbon buildings by 2050.

Climate-dedicated governance

The TCFD recommends that the board of a company or an investor should have oversight of and ultimate responsibility for climate-related risks and opportunities. This recommendation has been applied by many advanced practitioners: oversight of climate strategy is typically allocated to the board and executive levels of investment firms, and climate risk assessment and management is then typically allocated to analysts, portfolio managers, dedicated ESG personnel and/or external experts.

The specific governance structure will vary from one organisation to the next. For example, the PRI has seen examples of organisations where:

- Climate is among the issues overseen by a committee responsible for strategic planning or product development;

- Responsibility for climate-related issues is overseen by an audit committee

- The CEO or chair ensures that climate issues are considered throughout board deliberations;

- A committee on corporate responsibility exists, which oversees climate alongside other social and environmental issues[2]

Pillar 2: Strategy

The second pillar of the TCFD’s recommended disclosures relates to the way an organisation’s strategy may be impacted by climate-related issues. This includes:

- Describing what the organisation considers to be relevant climate-related risks and opportunities, and how these can have a material impact on its activity.

- Describing how resilient the organisation’s products/ assets and strategy may be to a range of different climate scenarios.

Figure 6: Sample of the different ways in which climate events can impact real assets

| Climate impacts on real assets: Example of railway asset in extreme heat | |

|---|---|

| Sample impacts on operations/services | Sample impacts on stakeholders |

| Railway tracks buckle | Heat stress for passengers and employees |

| Imposition of speed restrictions causing delays and disruption | Cost of additional services (for example, extra air-conditioning) |

| Associated services (eg overhead power lines) operate less efficiently | Lower passenger numbers |

| Inability or delays to carrying out essential maintenance | Changing work patterns (night shifts to avoid heat) |

| Subsidence issues undermine track stability | |

Climate Scenario Analysis

A fundamental element of this process is to conduct climate scenario analysis. This enables organisations to assess whether and how they may be affected by physical and transition risks, depending on different climate trajectories. Climate scenarios can be used to assess economic, strategic and operational resilience at both an organisational level, and at the level of individual assets within a portfolio. Carrying out credible scenario analysis also serves a purpose with external stakeholders – whether clients, regulators or civil society – by underlining an investor’s maturity and commitment on climate change issues.

Different types of investors will use scenario analysis for different purposes. For direct investors in real assets, it is likely to inform strategy and decision-making around the types of investment products to be offered; the resilience of investment strategies; asset selection; and the ongoing management of assets (see New Forests example below). For those investing through managers, the analysis should filter into initial asset allocation decisions and subsequently in manager selection, appointment and monitoring processes.

Either way, there should be a clear connection between conducting climate scenario analysis, the development and/ or adjustment of climate strategy, and the risk management plans that will implement in part the climate strategy.

To assist investors in developing their own scenario based analyses, several public sources are available, including the PRI report Implementing the TCFD recommendations: A guide for asset owners (2018), the Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC) report Navigating climate scenario analysis: A guide for institutional investors, and the TCFD’s Guidance on scenario analysis for non-financial companies. Although not specific to real assets, the guides help define the key elements of what scenario analysis should entail, and advice for overcoming associated challenges, including:

- The types of parameters and/or assumptions that feed into the scenario analysis, considering issues such as carbon prices, policy changes, technological developments, demographic variables, and so on.

- How to select which scenarios to use, the timeframes they should cover, and how to balance the use of both qualitative and quantitative analyses (where appropriate).

- The different business implications of each scenario, including financial, operational and resilience factors.

For more details, see resources such as the TCFD’s online scenario-analysis hub.

In November 2019, the UNEP FI released a report summarising the findings from a collaboration with Carbon Delta and 12 institutional investors. The joint project’s objective was to apply a scenario-based climate risk assessment methodology to a real estate portfolio, and analyse how the resulting quantitative metrics could improve investment decisions.

The report details the methodology co-developed by Carbon Delta on both physical and transition risks, the ‘Warming Potential’ and ‘Climate Value-at-Risk’ metrics, and the aggregated analysis of the sample portfolio. Several investor participants developed case studies providing their perspective on the project’s methodology and results, as well as potential improvements. For example, Aviva Investors discusses the inclusion of an aggressive scenario, as well as choosing a 15-year time horizon.

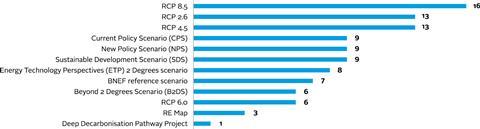

The 2020 PRI reporting framework asked signatories which physical climate and energy transition scenarios they used as part of their climate-related activities.

Number of real assets investors using a given climate scenario. Source: 2020 PRI climate snapshot

Among real assets investors, the scenarios most commonly used were the IPCC’s Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs): specifically, RCP 8.5, RCP 2.6, and RCP 4.5. The most widely used energy transition scenarios were those developed by the International Energy Agency (IEA). The PRI provides further details on reference climate scenarios here.

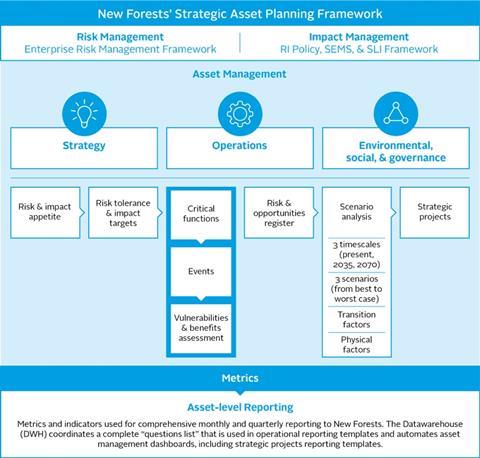

Forestry investment manager New Forests integrates scenario analysis within its proprietary strategic asset planning framework.

The framework takes users through a step-by-step process, beginning with establishing a risk and impact appetite and then setting a risk tolerance and impact targets appropriate to the investment mandate. The next steps require identification of “critical functions” that support investment return and valuation; New Forests provides an initial standardised set of critical functions appropriate for forestry investments, such as soil quality, land management, and silvicultural regime management. The critical functions are then assessed against a series of “event” exposures including acute physical, chronic physical, and transition climate risks. This results in a vulnerabilities and benefits assessment that populates a risk and opportunity register.

Using TCFD guidance, the risks and opportunities are evaluated for potential controls or mitigations over three timescales (present day, 2035, and 2070) and are assessed for residual risk/opportunity at each time scale. The presence and type of potential financial impact (asset value, liabilities, revenues, costs, or off balance sheet) is noted. Where the potential controls are deemed significant, these controls inform the creation of strategic projects.

The above steps generate the inputs that undergo a manual scenario analysis. New Forests did not identify a suitable single source of scenarios that was informative with regard to forestry assets, and so instead commissioned regionally specific scenarios based on best-available climate data from a range of sources. These included the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), international agencies, local research institutes, and government-supported data.

The scenarios address how physical and transition factors may affect critical functions in forestry assets. Each potential strategic project is stress-tested against the three scenarios. The results help New Forests and property managers to prioritise the strategic projects, identifying pathways to mitigate climate risk, enhance climate resilience, and pursue climate-related opportunities. These projects will be updated and reviewed annually, as part of strategic planning and budgeting.

Pillar 3: Risk Management

The third pillar of the TCFD’s recommendations focuses on the practices used by an organisation to identify, assess and manage climate-related risks throughout the investment process. Critical elements of this include:

- Describing the processes to identify, assess and manage material climate-related risks for each product or investment strategy;

- Describing, when relevant, how investors engage with their managers and/or directly with assets in relation to their practices on climate-related risks; and

- Describing how the management of climate-related risks fits in with overall risk management plans and processes.

The last point is particularly important, and links back to the need for a strong governance structure for addressing climate-related issues. Although many elements of climate change can be technically complex, the basic risk management process should not differ significantly from other such processes an organisation may conduct. It also requires communicating in a way that allows non-technical experts to understand the key issues, and integrate them into their own work.

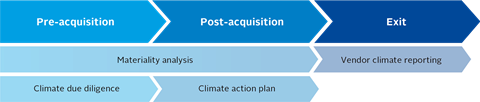

Below, we explore how climate-related issues can be integrated in different elements of the investment process, addressing most specifically:

- Materiality analysis, both pre- and post-investment, and due diligence

- Asset management activities, including climate action plans and ongoing monitoring

- Preparations for exiting an investment

Figure 7: Implementation of climate risk management throughout the investment process

For those investing in real assets through managers, most climate risk management will take place in the manager appointment, selection and monitoring process. The PRI has a suite of due diligence questionnaires for real estate, infrastructure, forestry and farmland investors, which cover the type of questions that investors should consider asking prospective managers. Currently the DDQs address managers’ ESG processes in general, rather than focusing on climate-related issues specifically. Nonetheless, many of the questions can act as a proxy for similar questions on managers’ approaches to climate change.

A. Materiality analysis and due diligence

Analysis of an asset’s exposure to climate risks and opportunities should be conducted during a climate due diligence exercise prior to acquisition, and subsequently throughout the holding period. The depth of this analysis will ultimately depend on the materiality of climate-related issues for each asset.

Materiality analysis

Assessment of climate risks and opportunities starts with a materiality assessment. This allows investors to segment and prioritise action on climate issues.

In practice, a materiality assessment consists of assessing if climate change can reasonably be expected to significantly impact an asset’s operations, the services it provides (in the case of infrastructure, for example), its supply chains, and key stakeholders such as employees, users or consumers, and local communities.

Factors typically analysed are the sector, size, location and regulatory environment of each asset, but climate risk analysis has added degrees of complexity given uncertainty over the direct and indirect impacts of climate change, particularly in the very long term. Nonetheless, this type of analysis can help investors define potentially severe risks, and have a clear vision on where to start taking climate related action.

There is a wide range of publicly available tools and resources to help real assets investors understand and assess material climate risks affecting their portfolio (see Figure 8, below). Alternatively, investors can work with external consultants to develop a tailor-made materiality matrix that fits with their investment philosophy. This exercise should be carried out periodically throughout the holding period of an investment, to ensure that the materiality analysis remains current, and that investment strategies or actions can be adapted if required.

| Name | Description | Link to online resource |

|---|---|---|

| SASB Materiality Map | SASB’s Materiality Map identifies 26 sustainability-related business issues and their associated accounting metrics. Infrastructure, real estate and forestry management are some of the sectors included in the tool. | https://materiality.sasb.org/ |

| CDC Group’s ESG Toolkit | This toolkit offers practical guidance for responsible investors in emerging markets. The sector profiles provide real assets investors with relevant sector-specific information on climate change. |

ESG Topics – Climate change: https://toolkit.cdcgroup.com/esg-topics/climate-change/ Sector profiles: https://toolkit.cdcgroup.com/sector-profiles/ |

| GRESB | GRESB assesses investor ESG performance across real assets and constructs industry performance benchmarks. It also provides a publicly available infrastructure materiality and scoring tool. |

https://gresb.com/ |

| GRI standards | The GRI standards provide companies with a framework to identify and communicate material topics. | https://www.globalreporting.org/ |

Due diligence

Based on the findings of a materiality analysis, more in depth climate due diligence should be conducted on particular assets or issues prior to an investment. While the scope of this due diligence is of course unique to each case, common elements can include:

- Consideration of the adaptive or mitigation measures adopted by assets in response to physical or transition risks.

- The level of understanding and expertise on climate related issues among management and key personnel at the asset level (or their operators, in cases where assets are managed by third parties). This includes awareness of regulatory and market developments, as well as the cost or value implications of different climate impacts on the asset.

- Whether the asset is certified against sector-specific sustainability standards, which can help support stronger performance on certain climate-related issues (for example, energy efficiency)[3]

The outcome of the climate due diligence process should then feed not only into the terms of an eventual transaction, but also into any post-acquisition action plan for the asset (see example below).

Established in 2017, STOA is an Infrastructure and Energy impact fund which finances infrastructure projects in emerging countries. Its commitment to climate change mitigation and adaptation is reflected by the fact that after three years of existence, its entire portfolio is compatible with the Paris Agreement.

To reach this point, STOA has developed a comprehensive and systematic climate due diligence process for prospective investments. This process requires the collaboration of the Environmental & Social and Investment teams and has three distinctive steps:

Step 1. Computing the Climate Footprint

The project’s climate footprint is calculated using the ’Bilan Carbone’, a tool developed by the French Development Agency (AFD, one of STOA’s two shareholders). This includes the project’s Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions. It establishes an estimate of the project’s climate footprint to feed into the decision-making process from a very early stage.

Step 2. Selectivity Matrix

The climate footprint is then assessed against a selectivity matrix that distinguishes three different categories of countries, based on their development level, and defines emissions thresholds. This process enables STOA to classify the feasibility of the project and reject highly emissive projects.

Step 3. Analysing the country’s climate context

For a project with potentially medium to high carbon emissions, a robust climate analysis context is carried out in order to assess the project’s alignment with the Paris Agreement. This includes a study of the project’s alignment with the country’s low-carbon strategy, an assessment of the project’s vulnerability and resilience to climate risks, and a qualitative estimation of the carbon lock-in risk.

This three-step analysis is continuously updated based on the availability of new data, from the start of the screening phase through to the final investment decision.

Assessing physical and transition risks

As noted earlier in the report, the TCFD makes clear that investors should consider both physical and transition risks in their climate materiality analysis and due diligence processes. This is not always straightforward as the tools and data available to real assets investors to assess these risks are still maturing.

Many investors continue to use a blend of qualitative and quantitative risk assessments, particularly in relation to physical risks, to determine their key vulnerabilities.

Figure 9 below summarises key considerations and important tools available to real assets investors for both physical and transition risks.

| Physical risks | Transition risks |

|---|---|

| Definition | |

| Physical risk refers to the effects of climate change on weather patterns, including increased incidence of extreme weather such as hurricanes and droughts. | Transition risk refers to the effects of large-scale shifts in the economy in response to climate change or efforts to mitigate it, such as public policy changes in support of low-carbon energy |

| Resource Availability | |

| There are an increasing number of organisations who have developed tools to assess exposure to physical climate risk, including specifically for different real assets. Some investors have taken these tools further, by factoring in adaptation or mitigation (prospective or actual) put in place at the asset level, to get an even more precise assessment of key risks. | Of all the real assets sectors, real estate benefits from the most advanced suite of tools to assess transition risk exposure. Providers such as CRREM and the UK Green Building Council have developed transition pathways, which allow users to model the types of measures needed to adapt properties to different climate scenarios. |

| Tools/Resources | |

|

Carbone 4: Climate Risk Impact Screening 427: Physical Climate Risk Application GRESB/Munich RE: Climate Risk Platform ClimateWise/CISL: Physical Risk Framework |

Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM) ClimateWise/CISL: Transition Risk Framework |

B. Asset Management

The holding phase of a climate strategy consists of translating climate risk assessment into relevant and concrete action plans, asset management and engagement with key partners, such as co-investors and relevant stakeholders. Where assets are being managed by third parties, this also requires building key climate-related objectives and targets into contracts.

The action plans are specific to each investment, and there is no correct way to develop action plans. However, effective action plans are likely to contain elements such as:

- Where relevant, awareness-raising and formal training activities on climate-related issues for top management and key personnel at the asset level. Where major gaps are identified, some investors may also choose to install a new management team with known expertise on climate issues.

- Ensuring that the asset has the right financial and human resources to deliver on the climate action plan.

- Defining key climate metrics that will allow the asset and investors to generate decision-useful information on ongoing performance against climate targets and objectives (see Pillar 4: Metrics and Targets).

- Ensuring that there is scope for the action plan to be modified based on the outcomes of the ongoing monitoring

In 2017, SWEN Capital Partners introduced a “climate meeting clause” for new investments. This clause requires GPs to hold a meeting with SWEN Capital Partners 18 months post subscription to a fund to talk about climate change and how it is integrated into the GP’s investment process. This meeting does not involve an in-depth and complex analysis of climate practices, but rather aims to begin a dialogue about climate as part of SWEN CP’s engagement with its GPs. As this clause is discussed before investing in a GP, this also results in developing climate awareness as early as the pre investment phase.

Given the long holding periods of most real assets investments, investors must be prepared to revisit their climate action plans and overall approaches to asset management on a regular basis. This is particularly important as the industry continues to grow in maturity on climate-related issues, with more tools and resources becoming available to support risk management efforts, and the longer-term impacts of climate change also becoming more apparent in time.

C. Exit Strategy: long-term thinking

Better practice on including more detailed information on climate risks and opportunities in vendor reports is likely to develop in the years ahead. At present, inclusion of such information is not widespread in the real assets industry. Common investor concerns over the practice include the fear that disclosing too much regarding climate risks would potentially harm the valuation of an asset.

However, there is strong rationale for providing such information. Again, the long-term nature of real assets investing is an important factor here. With the full impacts of some elements of climate change still uncertain in the long term, prospective buyers of real assets will increasingly want to know what type of measures have been put in place at the asset level to adapt to and mitigate against key physical and transition risks. A simplified way to conduct such due diligence when selling an asset would be to align the report to the TCFD structure, in order to make sure that all important climate topics are considered.

Pillar 4: Metrics and targets

The fourth pillar of the TCFD’s recommended disclosure refers to:

- The metrics and targets used by organisations to assess and manage material climate-related risks and opportunities;

- Disclosing the weighted average carbon intensity for each product or investment strategy.[4]

An organisation’s work around metrics and targets should stem from the processes described under Pillars 2 and 3. They form a critical element of how a climate strategy and its associated risk management plans should be implemented. However, they should also be part of a continuous feedback loop: progress towards key targets, as assessed by the metrics in use, will inform how climate strategies and risk management efforts need to be updated over time.

Target-setting

The TCFD guidance states that organisations “should describe their key climate-related targets such as those related to GHG emissions, water usage, energy usage, etc., in line with anticipated regulatory requirements or market constraints or other goals.”

From an emissions perspective, these targets are increasingly being framed by the need for investors in all asset classes to be aligned with the 2015 Paris Agreement (See Box 1); in other words, the need for investors to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

There is increasing literature available for investors to understand what target-setting for net zero may entail. The United Nations-convened Net Zero Asset Owners Alliance and the Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), for example, have both published recent guidance outlining the frameworks and elements required for credible target-setting. These include how organisations should aim to:

- Use science-based targets and methodologies wherever possible, based on the available data;

- Consider both top-down targets to set a clear direction and ambition, but also bottom-up targets to support decarbonisation processes at individual assets; and

- Set interim targets, ideally at five-year intervals, to track progress and allow for corrective action where necessary.

Both organisations’ documents include specific protocols for real estate investors, but not for other real assets, a reflection of how much further the real estate industry has advanced in developing methodologies for assessing net zero pathways.

Building expertise on metrics

Our research for this project devoted significant time to exploring the use of metrics by a range of advanced real assets investors. This research clearly identified that a consensus around core metrics, and overcoming some of the challenges associated with them, remains a work in progress. These challenges are not confined to real assets investing; the TCFD itself has recognised the need for more high-level guidance around metrics, and this is a priority area of work for the body in 2021. For that reason, the PRI is not presenting a definitive list of metrics in this guidance. In the text below, we instead discuss more broadly how organisations can approach the selection and use of different metrics, and some key considerations identified specifically in relation to real assets through our interviews and workshops with signatories.

In general, our research suggests that a more advanced use of metrics is heavily dependent on an organisation’s overall maturity in understanding and addressing climate-related issues. Indeed, many organisations consulted for this project emphasised the learning curve around the use of different metrics: by gaining expertise and experience through the application of ‘simpler’ or more universally agreed metrics (such as carbon footprints), organisations begin the process of understanding their relevance to both strategic and operational decision-making.

Based on these initial efforts, they can then go further in exploring different metrics. Based on our research for this project, four key factors stand out:

- Clear climate strategies and governance structures are in place (as detailed in the sections Pillar 1: Governance and Pillar 2: Strategy of this guidance), which provide clarity on how and why certain metrics are used.

- A willingness to test different metrics and targets internally to understand their value (or lack thereof) to climate strategy and risk management.

- Connected to the above, the most advanced organisations are prepared to use a range of climate metrics, rather than attempting to convey all climate risks and opportunities through a single metric.

- A commitment to providing or developing the right resources to procure data, which can underpin the use of different metrics, and to support alignment between different parts of the business (for example, the investment team and ESG team).

Choosing the ‘right’ climate-related metrics for real assets is not an exact science; it requires consideration of a range of factors, both internal and external to an organisation. Below, we discuss some important factors that real assets investors can study as they develop their work on metrics:

What are the use cases of potential metrics?

Not all metrics have the same uses. Some help assess a portfolio’s alignment with key climate goals; others measure climate risks and opportunities at asset or portfolio level; and so on. Understanding these different use cases, and whether they support climate strategy and risk management plans, may help organisations to consider which are the most appropriate.

Who are the end users of different metrics?

Not all metrics will be useful to all stakeholders. Many real assets investors interviewed for this report cited the example of Climate Value-at-Risk[5]: here, the role of the metric is to provide an overview of potential value that could be lost or gained based on physical and transition risks for the portfolio as a whole. This allows a single number or value to be reported to clients. On the other hand, many interviewees highlighted that it was not so useful from an asset management perspective, because asset level nuances are rarely taken into account.

Do the metrics help measure climate-related risks or opportunities, or both?

The TCFD recommends assessing and managing not just climate-related risks, but also opportunities; however, the majority of widely used metrics are either explicitly or implicitly directed towards risk. In real estate, however, tools such as CRREM can be used to identify properties that require less adaptation capital than others to bring in line with net zero expectations, highlighting how potential opportunities can be identified through certain metrics or tools.

Are the metrics qualitative or quantitative?

There are many quantitative metrics that assess transition risk and opportunity, particularly as it relates to mitigation metrics, and metrics related to standards. However, our interviews highlighted that qualitative risk assessments have an important role to play, often in relation to physical risks, and particularly at an individual asset level. Qualitative analysis still helps to fill gaps where widespread data might not be available and/or there is often a lack of confidence in the assumptions underlying the modelling used.

How can backward- and forward-looking metrics sit together?

For organisations to be aligned with the TCFD recommendations, they need to demonstrate a consideration of future physical and transition risks and opportunities. However, backward-looking metrics, which disclose the actual performance of an asset or portfolio, such as an asset’s carbon footprint, are generally more established than forward-looking metrics. Interviewees considered that they can also play a critical role in developing an evidence-based, consistent climate risk baseline, from which to develop forward-looking scenarios and associated metrics.

Do the metrics measure performance at asset or portfolio level?

Understanding if a metric is intended to provide information on an asset-by-asset or a portfolio-wide basis can also be an important consideration. Some metrics can provide insights into the interventions required to bring an asset in line with organisation-wide carbon targets; in certain cases, these can be aggregated at the portfolio level to provide a representation of wider risks, in a bottom-up approach. For example, if the required spend on adaptation or climate mitigation measures for each asset was known, this could then be communicated at the portfolio level.

Are available metrics and tools appropriate for use in different real assets sectors?

In general, the real estate sector has a better level of data quality and availability, more sophisticated tools and more refined approaches when selecting and calculating metrics. For example, transition pathways, such as CRREM, have only really been developed for the real estate sector to date, with the infrastructure, agriculture and timberland sectors all lagging in this respect. In many cases, the data availability and quality are considered too poor to be able to calculate or use similar pathways with great confidence.

US-based investment manager Nuveen, in collaboration with its farmland manager, Westchester, and timberland manager, GreenWood Resources, is developing a data-driven climate risk management framework. This will integrate climate science and transition scenarios into the firms’ investment processes. The focus is not only on mitigating climate risks, but also on capturing climate-related opportunities – such as those resulting from changing growing conditions, and nature based climate solutions that rely on plants’ natural ability to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The framework has three foundational pillars:

- Physical risk modelling: Nuveen is quantifying the potential impact of physical climate hazards upon real assets’ risk and return, modelling medium and long-term changes in value at risk by crop and species at the farm level (e.g. average annual losses or harvest yields), as well as unit cost of production (e.g. availability of inputs like water). The results of the modelling exercise are validated by its farmland business units and timberland operators, and then incorporated into underwriting, risk management and asset management practices.

- Transition opportunity analysis: Nuveen incorporates top-down scenario analysis into bottom-up investment processes to better understand the potential ‘upside case’ for managing real assets under a 1.5C transition scenario. This makes use of the Inevitable Policy Response’s (IPR) Forecast Policy Scenario (FPS), because of its unique focus on land-use change. Nuveen’s top-down analysis complements existing efforts to manage transition risks at the regional level, such as groundwater conservation in California and deforestation in Brazil.

- Carbon portfolio optimisation: Nuveen Real Assets is pioneering a portfolio optimisation framework to help investors maximise risk-adjusted returns alongside carbon outcomes, such as net zero emissions by 2050. The framework adapts the standard mean-variance portfolio optimisation model to include a third dimension – carbon emissions – alongside traditional risk and return inputs. This tool is able to suggest portfolio structures for any possible level of emissions that is desired, such as net-zero or even net-negative emissions. It generates a set of “carbon efficient frontiers”, with each frontier representing an optimal portfolio that maximises return for a given level of risk and net carbon emissions. Understanding these potential trade-offs, and the portfolio benefits of nature-based climate solutions, as well as quantifying risk-return and carbon in a unified framework can help inform asset allocation and portfolio design for net-zero.

Conclusion

Research and action on integrating climate-related issues into investment decisions is rapidly developing. Between the launch of the project and the completion of this guide, the landscape has continued to evolve, with a constant stream of announcements by regulators, asset owners, asset managers, banks and the corporate sector. The Covid-19 pandemic has placed further scrutiny on the actions of business and investors with regards to the environment, with a further expectation that the real assets industry can play a vital role in the concept of ‘building back better’.

We therefore hope that this guidance will support real assets investors, whether in real estate, infrastructure, forestry or farmland, to build awareness, develop greater capabilities and ultimately take more concerted action to implement the TCFD recommendations. This in turn will drive better management and mitigation of climate-related risks, but also lead to the identification and implementation of new opportunities. The PRI will continue to support the real assets industry with its efforts in this regard, by updating guidance where appropriate, developing new resources and supporting the continued growth of networks of like-minded investors to take action on this critical issue.

Downloads

Technical guide: TCFD for real assets investors (English)

PDF, Size 2.58 mbTechnical guide: TCFD for real assets investors (Japanese)

PDF, Size 7.33 mbTechnical guide: TCFD for real assets investors (Chinese)

PDF, Size 7.89 mb

References

[1] The Investment and Stewardship Policy Module of PRI’s 2021 Reporting Framework is available here

[2] For further guidance, see the World Economic Form and PwC’s report on creating effective climate governance on corporate boards

[3]There are a number of sustainability standards used to assess real asset projects. These standards help investors, developers and other stakeholders understand the overall sustainability of projects being developed, including in relation to climate change (e.g. assessing projects resilience). Examples include: BREEAM, LEED, NABERS (for Real Estate); SuRe, CEEQUAL, Envision, ISCA (for Infrastructure); FSC (for Forestry)

[4] For more details, see page 46 of this TCFD guidance

[5] See also Example: UNEP FI Real Estate TCFD Pilot Project within the Climate Scenario Analysis section of this guide