By Jitendra Aswani, Harvard University; Aneesh Raghunandan, London School of Economics; and Shivaram Rajagopal, Columbia University

Various stakeholders, including the US government, investors, and the media, show considerable interest in how US firms disclose – and will eventually reduce – their carbon emissions. Investors are also interested in whether such reductions by portfolio firms can contribute to greater stock returns and better operating performance.

In response to such demand among policy makers and practitioners, an emerging set of influential papers has found that there are strong links between carbon emissions and fundamental measures of firms’ financial performance, such as stock returns, operating profitability, and firm value.[1]

However, the results – and their interpretations – presented in these papers are highly dependent on measurement choices, some made by authors of academic studies and some by data vendors.

In our study, we highlight two potential issues:

(i) The use of total emissions data rather than emissions intensity (the ratio of emissions to revenue) as a primary measure of carbon risk; and

(ii) The quality of vendor-estimated carbon emissions figures.

Total emissions vs emissions intensity

While total emissions may be a good measure of economy-wide carbon risk, this is not a suitable measurement choice for understanding individual firms’ carbon risk; using a firm’s emissions intensity (the ratio of emissions to revenue) is a better way of measuring this.

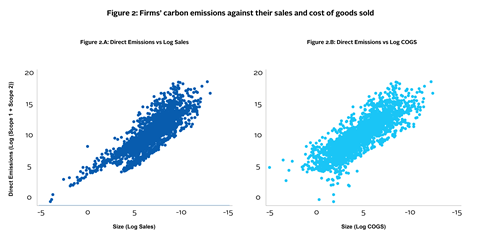

Carbon emissions arise from a firm’s core operations, therefore total emissions primarily show how much raw material it has used or how many goods it has produced and sold (see Figure 1), which can also be seen in Figure 2, where we plot firm-level carbon emissions (Scope 1 plus Scope 2) against sales and cost of goods sold (COGS).[2]

On a standalone basis, any correlation between total emissions and stock returns – the focus of most prior academic work – can only be interpreted as showing a link between a firm’s productivity, or revenue (a proxy for the quantity of units produced and sold), and its stock market performance.

Conversely, studying emissions intensity – a metric more commonly used by investors, which calculates the ratio of emissions to revenues – better reflects a firm’s emissions performance by avoiding automatic correlations with firm size.

Using firms’ total emissions rather than their emissions intensity to measure carbon risk is like using net income rather than ratio-based measures, such as return on assets, to measure financial performance.

Although it is important to recognise the relationship between emissions and revenue, we should also acknowledge that significant emitters concentrate within a few sectors, such as materials, energy, and utilities. Therefore, the association between emissions and stock returns has to be studied by correctly adjusting for sectoral differences in emissions.

The quality of vendor-estimated carbon emissions

Our study raises concerns about the reliability of emissions data estimated by vendors. We show that vendor-estimated emissions figures systematically differ from those disclosed directly by firms. This is even more concerning when we know that most observations in standard emissions databases are vendor-estimated.[3]

Therefore, any kind of statistical relationship between carbon emissions and stock returns based on this data is simply picking up the distributional differences between disclosed and estimated emissions.

Consistent with this argument, we show that the correlation between stock returns and total emissions data documented in prior research is driven entirely by vendor-estimated emissions, as opposed to actual emissions figures provided by firms.

We show that when focusing specifically on firms’ actual levels of carbon emissions, there is no link between emissions and stock market performance (i.e. there does not appear to be a carbon risk premium).

What did our findings reveal about emissions and financial performance?

To test whether carbon emissions are actually associated with stock returns and financial performance, we used data from a sample of 2,729 US firms from 2005-2019. We obtained emissions information from Trucost, which we merged with CRSP and Compustat for information on stock returns and firm characteristics.

Once we:

(i) examined emissions intensity rather than firms’ total emissions; and

(ii) accounted for vendor-estimated vs firm-disclosed actual emissions,

we did not find any evidence of a relationship between Scope 1, 2, or 3 emissions and stock market or fundamental financial performance.

Our findings suggest that responsible investors, policy makers, and academics may want to be cautious in interpreting correlations between a firm’s carbon emissions and valuation constructs (e.g. stock returns) or fundamental accounting data (operating profitability).

We take no position on whether disclosing and/or cutting emissions is desirable or not. We only argue that calculating emissions intensity (emissions by revenue) is a more suitable way to capture a firm’s carbon risk and that, based on this measurement, there is no correlation between carbon emissions and stock returns (i.e. no evidence of a carbon premium yet).

Nevertheless, we warn that increasing carbon pricing can affect this dynamic. Researchers and practitioners should also be careful in using vendor-estimated emissions figures that may fundamentally alter inferences about the link between emissions and financial performance.

However, we believe that firms disclosing their emissions on a widespread scale, as well as greater truth in advertising by emissions-related data vendors, will mitigate this latter issue.

This paper was presented at the PRI Academic Network Week 2022.

The PRI’s academic blog aims to bring investors insights from the latest academic research on responsible investment. It is written by academic guest contributors. Blog authors write in their individual capacity – posts do not necessarily represent a PRI view.

References

[1] Bolton, P. and Kacperczyk, M. (2021a). “Do Investors Care About Carbon Risk?” Journal of Financial Economics 142(2), 517-549.

Bolton, P. and Kacperczyk, M. (2021b). “Global Pricing of Carbon-Transition Risk.” Working paper, available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3550233.

Matsumura, E. M., Prakash. R., and Vera-Muñoz, S. C. (2014). “Firm-Value Effects of Carbon Emissions and Carbon Disclosures.” The Accounting Review 89(2), 695-724.

In, S. Y., Park, K. Y., and Monk, A. (2019). “Is ‘Being Green’ Rewarded in the Market? An Empirical Investigation of Decarbonization and Stock Returns.” Stanford Global Project Center Working Paper, available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3020304.

Garvey G. T., Iyer, M., and Nash, J. (2018). “Carbon Footprint and Productivity: Does the “E” in ESG Capture Efficiency as Well as Environment?” Journal of Investment Management 16(1), 59-69.

[2] Emissions data are usually reported under the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Protocol and are measured in tonnes of carbon dioxide per year. The GHG Protocol specifies three scopes of emissions. Scope 1 reflects direct emissions sources owned or controlled by a company. Scope 2 emissions reflect the consumption of purchased electricity, steam, or other energy sources. Scope 3 encompasses all other emissions associated with a company’s operations that are not directly owned or controlled by the company.

[3] Nevertheless, we believe that further emissions disclosure by firms and convergence among vendors’ methodologies to estimate undisclosed emissions will mitigate these problems.