Aniruddh Mohan and Nicholas Z. Muller, Carnegie Mellon University

Policy makers, firms, investors and the public rely on metrics such as gross domestic product (GDP) for information on economic performance and growth, while sustainability is typically assessed through measures of emissions.

In a recent paper, we argue that what matters to societal welfare is not the physical tonnage of emissions, but the monetary damage caused by them.

Putting a price on impact allows for comparison across pollutants. Monetary damage can be deducted from traditional measures of production, or firm value.

Fundamentally, it is damage, or impact, that determines sustainability and therefore, this metric should guide investors as they pursue environmentally responsible asset allocations.

Why using the right measures matters

The measure of a country’s GDP does not account for environmental impacts, the value of leisure time, home production, and other out-of-market activities.

The dearth of information on environmental outcomes is especially crucial for investors because it leads to a reliance on heterogeneous sources of data and ambiguous criteria for assessing environmental performance.

In our paper, we augment national economic data with measures of environmental damage for more than 160 countries between 1998 and 2018.

We derive environmentally adjusted value added (EVA) (Muller, 2014), which deducts pollution damage (gross external damage or GED) from reported GDP.

GED is the total damage from unabated emissions; it is the unpriced cost associated with the production and consumption of market goods and services. So, even though in some countries environmental policies have succeeded in reducing emissions, GED tracks what is still being emitted.

By including external costs, EVA is a more holistic measure of national welfare than GDP. This approach is based on extensive literature on environmental accounting (Nordhaus and Tobin, 1973; Bartelmus, 2009; Muller, Mendelsohn, and Nordhaus, 2011).

Our EVA and GED calculations – the first at a global level – draw on country-year CO2 emissions data as well as satellite and ground-based measurements of particulate matter air pollution.

What difference does EVA make to definitions of sustainability?

Let us explore China, the country with the highest level of CO2 emissions and rapidly increasing GDP. Average levels of ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) peaked in 2011, while CO2 emissions have been flat in recent years.

From this perspective, it may be reasonable to conclude that China is approaching sustainable growth.

Yet, monetary damages from these two pollutants have increased 50% since 2011 and averaged an annual growth rate of 5%, with real per-capita damages doubling every 14 years.

How can damages from pollution be growing if emissions are not?

Looking at the primary contributor to climate change, CO2, the damage from each additional ton emitted (the marginal damage) increases as the global stock of CO2 increases. A ton of CO2 emitted in 2020 therefore has far higher marginal damage than a ton emitted in 1970. Therefore, even as CO2 emissions fall, their damage may be growing due to the increase in marginal damage of each ton emitted.

Thus, if emissions fall as a country approaches its balanced growth path (where savings are offset by depreciation and real income stops growing) its economy may appear to be growing sustainably, if policy makers focus their analysis on emissions.

Damages, on the other hand, can continue to rise, unchecked – painting a very different picture which cannot satisfy any reasonable definition of sustainability.

Focusing on damages not emissions

Policy makers should therefore focus on damages not emissions.

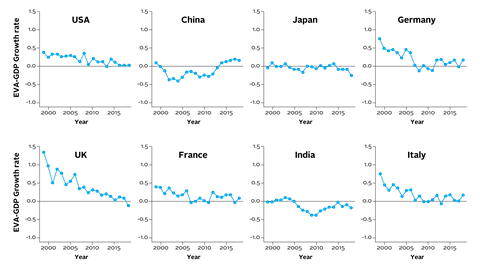

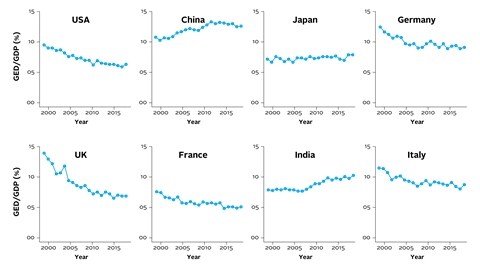

We calculate pollution intensity for countries based on level of damage rather than emissions, using growth rates based on our adjusted measures of income. These results for the world’s major economies are shown in figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1 shows that high-income countries have EVA growth rates that exceeded GDP growth prior to the financial crisis. In the late 1990s, the differences were as much as 1.0% annually in Western Europe, and about 0.3% in the US.

EVA growth is higher because during this period pollution damages in these economies fell as GDP grew (see Figure 2), due to tighter environmental policy, a shift away from coal-based power generation, greater energy efficiency measures, and the offshoring of heavy manufacturing.

In India and China, we see the opposite. EVA growth has lagged GDP growth as these economies grew at a rapid pace and became more intensive polluters. Pollution problems, particularly in urban areas, became prominent in both countries during this time.

From 2000 until 2011, EVA growth in China was as much as 0.5% slower than GDP. While real GDP per capita increased more than five-fold from 1998 to 2018, pollution damage increased by a factor of nearly seven in real terms, placing a drag on economic growth when measured using EVA. These results are not captured by metrics such as GDP.

In India, as the economy began to grow rapidly in 2005, EVA growth fell short of GDP by as much as 50 basis points annually. Over the 21-year period considered, real GDP per capita has doubled, while pollution damages or GED are five times higher – costs which standard metrics such as GDP miss.

Conclusions

As unified, efficient global environmental policy appears beyond reach, the role of environmentally conscious investors in allocating capital to firms, industries, and sectors with limited environmental impact is increasingly important.

Metrics that provide guidance to investors on environmental performance tend to be based on emissions and framing them in non-monetary terms makes them challenging to apply.

We argue that sustainability is determined by impact, not physical emissions, and that impacts should be expressed in monetary terms. This allows for aggregation across pollutants as well as impact areas such as human health, physical property, and crops.

Monetising damage also permits calculations of net firm, industry, or economy value-add as well as growth. Ultimately, these form important criteria in how investors allocate capital.

Our calculations provide a different lens – that is cognisant of environmental impacts – to assess these. The results and methods, already framed in terms of monetary impacts, can inform investors as they seek to align their portfolios with environmental goals and adjust exposure to climate, pollution, and regulatory risk.

This blog is written by academic guest contributors. Our goal is to contribute to the broader debate around topical issues and to help showcase research in support of our signatories and the wider community.

Please note that although you can expect to find some posts here that broadly accord with the PRI’s official views, the blog authors write in their individual capacity and there is no “house view”. Nor do the views and opinions expressed on this blog constitute financial or other professional advice.

If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected].