By Söhnke M. Bartram, University of Warwick and CEPR, Kewei Hou, Ohio State University, and Sehoon Kim, University of Florida

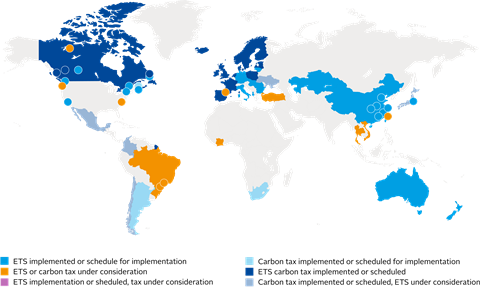

In response to mounting concerns of climate change risk, governments around the world are pushing for regulations to curb greenhouse gas emissions in various forms and with varying intensity. There is no consensus on what the optimal policy approach might be and as a result, climate policies are highly fragmented across different jurisdictions (see Figure 1). This has important implications for how successful localised policies can be, which is the focus of our study, Real Effects of Climate Policy: Financial Constraints and Spillovers.

In 2013, California became the first US state to implement a multi-sector cap-and-trade system to regulate all industrial greenhouse gas emissions. It was launched as a pragmatic approach to managing the amount of greenhouse gas produced annually by companies within the state. In our study, we examine the impact of the cap-and-trade rule in California and reveal some of its unintended consequences. We find that:

- Some companies shift greenhouse gas emissions from their California plants to plants located in other states in response to the policy;

- These companies increase their overall emissions rather than reducing them as intended by the policy;

- Financial constraints — the companies’ ability to access funding — play a critical role in shaping their responses to the policy.

Our research, funded by the Risk Institute at The Ohio State University and the British Academy/Leverhulme Trust, provides insights about climate policy, how companies respond to these regulations, and what policymakers should know about the effectiveness and limitations of climate regulation strategies.

Who responds? Access to financing and emissions shifting

When California’s cap-and-trade policy was announced in 2013, a major Texas-based manufacturer of transportation fuels reduced its emissions at one of its largest California refineries, in Los Angeles County, by 8% over the next three years. However, it also sharply increased emissions (by more than 10%) at some of its largest refineries in other states, including in New Orleans, Louisiana and Jefferson, Texas. Prior to the enactment of the policy, the firm, still reeling from the financial crisis a few years earlier, vehemently opposed the adoption of a cap-and-trade.

We conduct a systematic study to investigate whether this kind of response has been typical across companies. To this end, we examine detailed plant-level data on greenhouse gas emissions and parent company ownership made available by the US Environmental Protection Agency. Our dataset includes 2,806 industrial plants and 511 publicly listed firms over the sample period, 2010 to 2015. We focus on the behaviour of industrial corporations around 2013, when the California cap-and-trade policy was introduced.

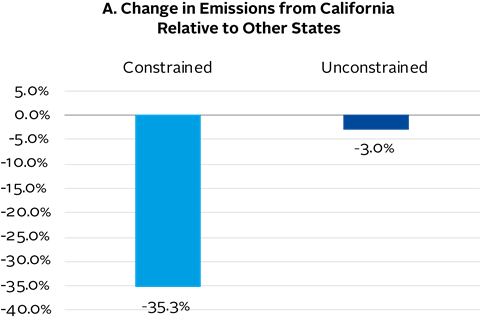

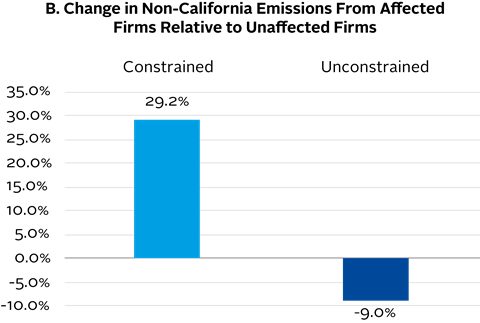

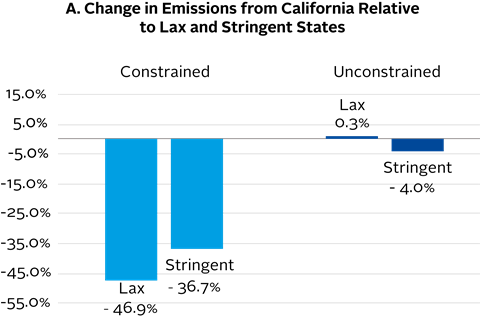

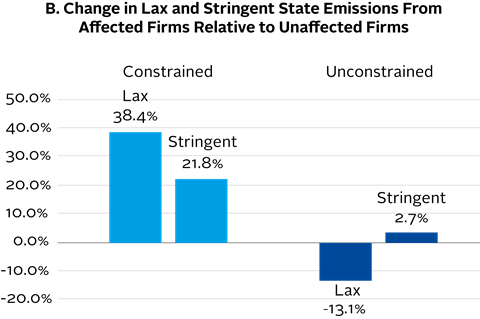

We document significant differences in how firms respond to the policy. Financially constrained firms (typically small and medium sized companies with limited access to capital) reduce greenhouse gas emissions at their plants located in California by 35% relative to plants they own in other states. However, these companies also increase emissions by 29% at plants in other states, compared to plants in those states owned by firms without a presence in California.

In sharp contrast, financially unconstrained companies (those with ample access to capital) do not adjust plant emissions at all in response to the new cap-and-trade regulation — in California or in other states. This suggests that the regulation is not costly enough for big companies with deep pockets, but rather a slap on the wrist for such firms.

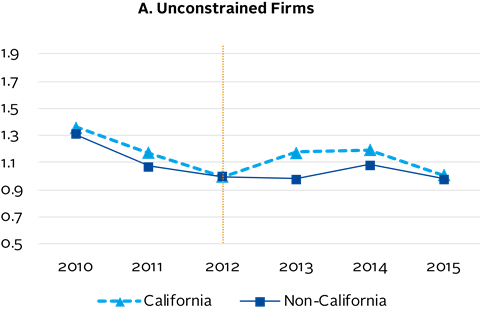

In short, it is for smaller companies or those having a hard time raising capital to finance their projects that the policy has a large distortionary impact. Some of these companies choose to move their emissions elsewhere because they cannot afford the incremental costs of the cap-and-trade. These results are illustrated in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2a: Year-by-year changes in plant emissions around the implementation of the California cap-and-trade

Figure 2b: Year-by-year changes in plant emissions around the implementation of the California cap-and-trade

This response partially reflects the appeal of cheaper, less-stringent regulatory environments available to financially constrained companies in other parts of the country (see Figure 4). It also reflects the reallocation by companies that had not been investing in clean technologies and thus were not readily prepared to shield themselves from the new regulatory costs. While this is an adverse outcome from a social and environmental perspective, financially constrained companies are likely behaving optimally from a shareholders’ point of view, highlighting the divergence between shareholder and stakeholder values.

Global effects of local policies

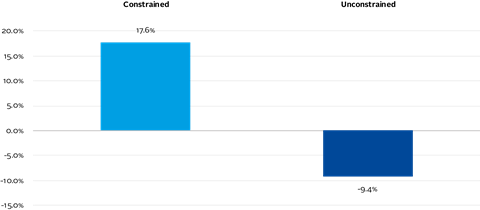

A critical policy implication of this reallocation is that the cap-and-trade may not lead to the desired reduction in greenhouse gas emissions globally. To the contrary, we find that financially constrained firms with plants in California and in other states increase their total emissions by 18% as a result of their reallocation, rather than decreasing them, undermining the goal of the cap-and-trade — and of climate policies in general — to combat climate change at the global level. This result is encapsulated by Figure 5.

The data supports our hypothesis that, for firms with limited access to capital, it is more attractive to reallocate their greenhouse gas emissions and plant ownership away from California to avoid the heightened regulatory costs that make doing business in the state expensive. This unintended consequence corresponds to an increase in emissions in less-regulated states and regions throughout the country, while resulting in a reduction in economic activity in sectors within California that are required to curb emissions, as evidenced by a 13% decline in emission-heavy sector employment.

Policy implications

In conclusion, climate policies designed and implemented at the local level — such as the California cap-and-trade — are unlikely to be effective at addressing climate change as they are theoretically proposed in a vacuum. For companies with ample access to capital, increased regulatory costs from the cap-and-trade rule are not significant enough to deter them from polluting. These costs only raise the burden for less financially capable businesses and industries, discouraging them from investing and producing in states with costly climate change policies while they outsource — and potentially increase — their emissions at plants they own in less-regulated states.

Our study contributes to the understanding of the interplay between climate policy and firm behaviour. It provides a steppingstone towards more effectively coordinated solutions to climate change by informing policy makers of the potential externalities from regionally segmented climate policies. This is important because if localised climate policies prove ineffective even within one country, they are unlikely to have the intended effect of reducing emissions on a global scale across countries. It is important for policymakers to realise that climate change solutions such as cap-and-trade — proposed at the local level — must recognise and account for regulatory differences regionally and globally.

Our findings point to two policy guidelines: (1) Given the geographically diversified nature of firms’ operations, climate policies should be harmonised across jurisdictions in order to minimise leakages. (2) Given that financially constrained firms have stronger incentives to reallocate, policymakers should carefully devise appropriately differentiated subsidies to mitigate distortions from implementing climate policies.

This blog is written by academic guest contributors. Our goal is to contribute to the broader debate around topical issues and to help showcase research in support of our signatories and the wider community.

Please note that although you can expect to find some posts here that broadly accord with the PRI’s official views, the blog authors write in their individual capacity and there is no “house view”. Nor do the views and opinions expressed on this blog constitute financial or other professional advice.

If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected].