For listed equity investors, the decision to engage with or divest from ESG laggards depends on the ESG issues concerned as well as the (sustainability) objectives of their clients and beneficiaries.

The two are not mutually exclusive – many investors favour a stewardship-first approach that includes divestment as the final step in an escalation strategy. Yet divestment may be more effective in some contexts than others.

The role of divestment in shaping sustainability outcomes

Investors increasingly recognise that the real-world sustainability outcomes and systemic issues they contribute to shaping through their investment activities will feed into the financial risks they face and are considering the role divestment can play in pursuing these outcomes.

Divestment reduces investors’ ability to directly influence the sustainability performance of investees. Evidence suggests that its financial impact on investees is unlikely to alter corporate behaviour. It may have more far-reaching consequences for public and market perceptions of an industry or company, though this is speculative.

Current trends such as the growth in passive investing, acquisitions of apparently undervalued assets by short-term investors, and improvements in investor stewardship may further weaken the case for divestment going forward.

Key factors when considering divestment

There are different considerations that may lead divestment or engagement to be more effective in shaping sustainability outcomes:

| Factors favouring divestment | Factors favouring engagement |

|---|---|

|

Investor is seeking value-alignment |

Investor is seeking real-world impact |

|

Poor opportunities to transition to a more sustainable business model |

Issue is systemic and non-diversifiable |

|

Investors have low leverage, e.g. a controlled company, lack of legal recourse |

Investors have or can improve leverage by working collaboratively |

|

Other escalation measures have already been exhausted |

Alternative escalation measures remain open to investors |

|

Fiduciary constraints on use of divestment |

Russian invasion of Ukraine

As this paper was being finalised, the Russian invasion of Ukraine was causing many investors and companies to seek to divest assets linked to Russia. This may prompt investors to evaluate other holdings that raise similar risks or concerns around negative outcomes such as human rights violations.

Divestment and net-zero commitments

The growing number of investors that have made commitments to achieve net-zero emissions in their portfolio by 2050 are likely to face increased pressure to divest high-emitting holdings. There is then a risk that the net-zero movement results in a subset of leading investors with greener portfolios, while the broader economy remains largely unchanged.

Advocating for and supporting the acceleration of high-emitting companies’ transition plans through stewardship activities will be among the most impactful actions that investors can take. However, not all companies will have viable options to transition to a low-carbon economy.

Investors in such companies will need to consider whether a managed decline of assets or public policy change are more likely to lead to decarbonisation aligned with the Paris Agreement.

Addressing greenwashing concerns

Demonstrating their commitment to sustainability outcomes can be difficult for listed equity investors, with both divestment and engagement approaches raising potential concerns of greenwashing.

Investors can mitigate these by embedding a range of levers and escalation measures in their stewardship policies and practices and reporting publicly on progress. They can:

- Engage directly with the company to address the relevant issue

- Join or form a collaborative stewardship initiative that includes the company as an engagement target

- File, co-file or support a shareholder proposal[1] setting expectations for sustainability performance improvements

- Vote against relevant members of the board of directors and disclose the rationale for doing so

- Consider shareholder litigation in respect of the company’s failure to address the issue

If divesting, investors can strengthen the signalling effect of such a move, and thus engage in responsible divestment, by publicly communicating (i) the reasons for doing so and (ii) the sustainability performance criteria which, if met by the company, may lead to re-investment.

Deploying broader influence

Proponents of divestment and engagement agree that using one approach in isolation will not be enough to eliminate systemic risks and to achieve ambitious sustainability goals such as the Paris Agreement or the Sustainable Development Goals.

Investors will need to go beyond direct stewardship of their investees to influence the market in which they operate, including by:

- considering whether and how policy change can support progress on ESG issues and incorporating policy engagement into their stewardship approach;

- considering engagement with index providers and stock exchanges to delist or exclude companies that fail to achieve minimum sustainability performance thresholds.

Introduction

One of the longest-running debates in responsible investment has been whether listed equity investors pursuing sustainability objectives should engage with ESG laggards in which they are invested or divest their holdings.

There is of course no straightforward answer to this question. Much will depend on the issues concerned and the objectives of investors, their clients and beneficiaries.

Nor are these mutually exclusive strategies; many investors favour a stewardship-first approach that includes divestment as the final step in an escalation strategy.

Yet even after an asset is divested, the ESG issues associated with it can have a negative financial impact on an investor’s broader portfolio, particularly as listed companies’ global footprints tend to be larger and divestments rarely directly impact their financial position.

Under its Active Ownership 2.0 programme, the PRI has put forward the case for a stewardship approach that is much more focused on sustainability outcomes, whereby investors consider:

- systemic issues and the interdependencies of portfolio assets to a greater extent; and

- how their influence can be deployed to achieve global goals such as the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals.

Investors wanting to pursue such sustainability outcomes may need to adjust how they make a divestment decision or formulate an overall approach to divestment, as this paper sets out.

We define divestment as a complete exit from the shareholding of a company. However, many of the considerations set out here apply equally to partial divestments, or the underweighting of stocks based on ESG criteria.

Where this paper refers to an engagement approach, this is intended to encapsulate the broad array of direct stewardship tools that are used in parallel with robust engagement, such as voting and escalation measures.

The role of divestment in shaping sustainability outcomes

This section summarises common uses of divestment in responsible investment strategies, and the limited evidence of divestment influencing real-world sustainability outcomes.

The rise of divestment as a strategy

The practice of divesting from companies involved in activities seen as incompatible with a set of beliefs or values has a long history within responsible investment.

Yet it was not until the 1970s and 1980s that a divestment campaign sought to affect real-world outcomes, with some institutional investors divesting from companies with operations in apartheid South Africa, and multinational companies spinning off their South African divisions.

Today, institutional investors face greater expectations from their stakeholders to divest from companies associated with a range of issues, including tobacco, weaponry and private prisons.

Yet the area where divestment has become most widespread is fossil fuel-related assets. There are now estimated to be 1,500 institutions with almost US$40 trillion in assets that have publicly committed to some form of fossil fuel divestment (though the scope of assets excluded varies significantly).[2]

As the number of investors that have committed to achieving net-zero emissions in their portfolio by 2050 rapidly grows, consideration of divestment as a strategy to realise that goal is likely to come to the forefront.

Divestment and sustainability outcomes

Investors are increasingly recognising that the real-world sustainability outcomes and systemic issues they contribute to shaping through their investment activities will feed into the financial risks they face. This is reflected in the PRI’s recent work on active ownership and investing with SDG outcomes.

The PRI defines systemic issues as “issues that have effects across multiple companies, sectors, markets and/or economies. Impacts caused by one market participant can lead to consequences across the system, including the common economic, environmental and social assets on which returns, and beneficiary interests depend.”

An investor will generally have a legal obligation to consider what, if anything, it can do to mitigate such risks where material (through a combination of capital allocation and stewardship) and to act accordingly, as explored in A Legal Framework for Impact: Sustainability impact in decision-making, a report published in 2021 by the PRI, UNEP FI and The Generational Foundation.

In the case of climate change, a minority of publicly listed companies are outsized contributors to excessive carbon emissions that will lead to increases in natural disasters, abrupt policy changes and volatility, thus threatening portfolio-wide value.

Divesting from such companies may reduce investors’ exposure to the risk of stranded assets. However, it is unlikely to have a discernible impact on their portfolio-wide exposure to physical climate risk, nor to the broader consequences of climate-induced societal upheaval. In such cases, divestment reduces investors’ ability to mitigate the risks and negative outcomes posed to their portfolios and beneficiaries.

Other ESG exposures are similarly difficult for investors to diversify away from. For example, economic inequality (including the poor working conditions that factor into this issue) contributes to political and economic instability, reduced consumer demand and rent-seeking.[3]

Yet these effects are not limited to companies with poor ESG practices; they are borne by companies and assets across entire economies.

Where the poor sustainability performance of a subset of companies exacerbates the risks faced in their broader portfolios, investors should not view divestment as a way to eliminate those risks. The key question then becomes whether engagement or divestment is a more effective tool to encourage change at those companies.

Impact of divestment on corporate behaviour

The evidence on whether divestment has led companies to adopt more sustainable practices is mixed. Particularly when compared with engagement, many academics have found divestment has a limited effect – if any – on shaping target companies’ decision making.[4]

The impact of divestment on companies’ cost of capital has been considered insufficient to affect their internal investment decisions. Yet exceptions to this view exist[5] and other researchers have found only limited improvements in sustainability performance resulting from institutional investor ownership.[6]

Many investors consider divestment to be an escalation method or ultimate sanction when investee companies are unresponsive to engagement efforts.[7] Under these circumstances, divestment can communicate to the wider market that the investor believes the targeted company’s long-term strategy is likely to remain misaligned with relevant sustainability performance thresholds.

The threat of divestment may be necessary to ensure some companies are receptive to engagement. Yet for others, the knowledge that vocal shareholders may eventually divest could also disincentivise them from acting on shareholder concerns, believing they can wait these shareholders out.

It is possible that even if divestment has little direct effect on individual companies’ decision making, it may contribute to broader normative shifts that shape public perceptions of a given industry and increase the likelihood of public policy interventions targeting that industry. Many proponents of divestment believe this is the key impact of such a strategy, though its effectiveness is speculative and difficult to measure.

Current trends could lead to a further weakening of divestment as a strategy for influencing corporate behaviour.

With continued asset growth from passive investors tracking broad-based indices, there will likely be long-term institutional demand for a substantial portion of large-cap companies’ securities, unless exclusions are considered for existing indices or there is a significant change in the uptake of alternative indices (see Engage stock exchanges and index providers).

Furthermore, should divestments succeed in increasing a company’s cost of capital, this may increase their attractiveness for some hedge funds and private equity investors with shorter-term investment horizons.[8]

Improving ESG incorporation and stewardship practices among investors may also improve the prospects of engagement compared with divestment.

Many jurisdictions have introduced or strengthened stewardship regulations or soft law; over 20 jurisdictions now have stewardship codes, as highlighted in the PRI regulation database. Investors also face increased scrutiny from other stakeholders of how they exercise stewardship. This has contributed to a rise in support for ESG-related shareholder proposals in recent years.[9]

The Ukrainian crisis and divestment of Russian assets

As this paper was being finalised, the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, was leading a significant number of investors and companies to divest assets linked to Russia , and many index providers to exclude Russian securities from equity and bond indices .

While investor divestments of equities and other assets tied to a region is not new, the scale and speed of investor action in this instance is unprecedented. As many organisations are yet to complete their divestments, and new announcements continue to be made, the long-term effects of these decisions will not be known for some time.

The investor case for divestment related to these circumstances is stronger than with other ESG issues discussed in this paper. When an investor’s concern is a company’s links to a particular state/region, engagement is not a viable option as the intent is not to influence corporate behaviour – rather the divestments are a contribution towards a larger package of economic sanctions led by policy makers.

Nonetheless, investors should also consider the potential for adverse impacts arising from divestment decisions, in line with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights ( see section on Influence below ). Investors should also be transparent with stakeholders about the extent to which divestment decisions are motivated by risk management, ethical or values-based alignment and/or an attempt to shape real-world outcomes.

Where investors are divesting for value-alignment or real-world outcomes purposes, they should evaluate broader portfolio holdings – for example, in regions with a high risk of human rights violations – for their consistency with these purposes. Investors may also devise and communicate expectations for investee companies as to whether and under what circumstances they support their continued presence in a region.

While conflict between nations is not under the direct influence of investors, there is still much that investors with an ESG approach can do to address the underlying ESG issues which drive or exacerbate armed conflict, and mitigate its impacts when it does occur. This involves taking a robust stewardship approach to addressing ESG issues in areas such as energy policy, human rights, corruption and global governance.

The PRI will continue monitoring developments and providing guidance on what international conflict means for responsible investors .

Key factors when considering divestment

This section summarises different considerations that may lead divestment or engagement to be more effective in shaping sustainability outcomes.

Table 1: Deciding whether to divest or engage

| Factors favouring divestment | Factors favouring engagement |

|---|---|

|

Investor is seeking value-alignment |

Investor is seeking real-world impact |

|

Poor opportunities to transition to a more sustainable business model |

Issue is systemic and non-diversifiable |

|

Investors have low leverage, e.g. a controlled company, lack of legal recourse |

Investors have or can improve their leverage by working collaboratively |

|

Other escalation measures have already been exhausted |

Alternative escalation measures remain open to investors |

|

Fiduciary constraints on use of divestment |

Client and/or beneficiary preferences

The suitability of divesting from assets with poor ESG practices must be considered in relation to the objectives and motivations of an investor’s clients and/or beneficiaries.

Clients and beneficiaries may favour incorporating ESG factors into investments for different reasons: to optimise risk-adjusted portfolio returns, to select a portfolio aligned with their values, or to contribute to real-world impact.

Where an investor is primarily seeking value alignment – i.e. not wishing to profit from industries or business practices that violate their ethical beliefs – divestment (or pre-investment screening) will often be appropriate, particularly when the business practices at issue are unlikely to change in the medium term. This will be the case for many traditional targets of values-based screening, such as tobacco, weaponry and gambling.[10]

By contrast, where clients or beneficiaries have real-world impact goals – or their financial objectives may be instrumentally met by achieving real-world impacts – an engagement approach might be more appropriate.

Remaining invested in laggard ESG companies to improve their sustainability performance carries reputational risk, however. Institutional investors – and asset owners in particular – increasingly face pressure from beneficiaries and the public to divest fossil fuel assets, for example.

Such pressure can be motivated by misconceptions regarding the connection between secondary market allocations and real-world impact, with some believing that divesting from listed equity investments directly affects corporate finances or emissions.[11]

This misconception can provide an opportunity to engage beneficiaries on their sustainability preferences, as demonstrated in Figure 1 below.

If beneficiaries are motivated by achieving a positive impact through their investments, as opposed to simple value alignment, these preferences may be better satisfied by a forceful stewardship approach, rather than divesting.

This is discussed further in PRI (2021) Understanding and aligning with beneficiaries’ sustainability preferences. Some investors have reported more of their beneficiaries supporting engagement once they better understood the investors’ approach.[12]

Figure 1: Creating a virtuous cycle of beneficiary engagement

Where an investor has indicated that they will address client or beneficiary concerns through engagement rather than by divesting assets, it is important that this is supported by a robust stewardship strategy and ongoing transparency to ensure accountability (see Addressing greenwashing concerns).

Nature of ESG issue

By definition, the risks posed by systemic issues cannot be mitigated simply by diversifying the investments in a portfolio. If such risks materialised, they would damage the performance of an entire portfolio and all portfolios exposed to the relevant systems.

Given that investors cannot diversify away their exposure to systemic issues, and the limited evidence of divestment impacting listed companies’ sustainability performance, an engagement approach will often be most appropriate with respect to such issues.

Transition opportunities

Investors will need to consider whether there are realistic opportunities for companies or sectors to transition to a more sustainable business model.

They should distinguish between where a negative sustainability outcome is largely intrinsic to the business model (e.g. the health effects of tobacco products) or relates to particular practices that they could improve through engagement (e.g. human rights issues in apparel supply chains).

In the former case, the prospect of engagement delivering improved sustainability performance may be weak. Investors will need to consider whether a managed decline approach, which seeks to return capital to shareholders, or public policy change, are more likely to reduce the negative sustainability outcomes associated with the issue.

Fiduciary implications

In general, investors’ risk measurement practices may place too much weight on performance against benchmarks that do not adequately integrate sustainability factors, rather than on providing an appropriate investment return to beneficiaries over the long term, as discussed in A Legal Framework for Impact .

Nonetheless, in certain jurisdictions investors may be subject to regulations that curtail their ability to diverge from a performance benchmark. [13]

This can make divestment – or pre-investment screening – unsuitable, as these activities limit the investment universe and by extension, change the risk-return characteristics of a portfolio.

In contrast, taking an engagement approach would not directly impact portfolio composition, while any impact on investment performance in relation to a given company would be shared across all investors and reflected in the relevant benchmarks.

Influence

A final consideration will be whether the context and circumstances of the investment permit an investor to develop sufficient influence to affect investee decision making – those acting alone may struggle, for example.

Investors seeking to shape sustainability outcomes should consider how to increase their influence before divesting an asset.

They should consider collaborating with their peers, which brings added benefits such as sharing costs and expertise, and with other stakeholders, such as representatives of communities affected by the ESG issue[14], NGOs[15] and company insiders, which can also help refine their engagement asks.

Investors can also increase their influence over a target company by expanding the scope of their engagement. As many companies raise capital via debt markets, they may have a greater impact on corporate behaviour by refusing to participate in bond issuances than by divesting listed equity holdings, known as an “Engage our equities, deny our debt” approach.[16] Investors can also engage with a company’s supply chain.

Structural limitations to their influence may lead some investors to favour divestment. This will often be the case in controlled companies, or those with dual-class share structures, which give company insiders or affiliates de facto control. Even in such companies, shareholders often have access to escalation measures such as the right to initiate legal action against the company or appointed officers.

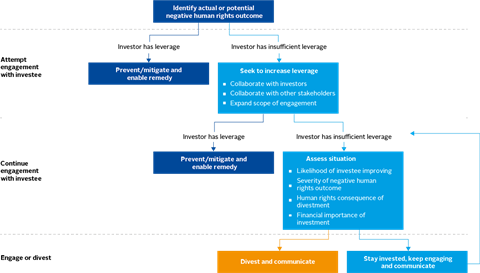

Investors will need to weigh their prospects for increasing their influence against the negative outcomes they might be exposed to – such as human rights violations – by remaining invested in the asset, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Example of incorporating influence (or leverage[17])into a human rights stewardship strategy

Divestment and net-zero commitments

This section summarises considerations for divesting from high-emitting assets to achieve net-zero goals.

Since the launch of the UN-convened Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance (NZAOA) in early 2020, the number of investors committing to achieve net-zero emissions in their portfolios by 2050 has grown massively – as of November 2021 an estimated 450 firms in the financial sector across 45 countries had done so.

Such investors are likely to face increased pressure to divest holdings that are not aligned with a net-zero-by-2050 trajectory, in order to achieve interim decarbonisation targets and to demonstrate the seriousness of their commitments.

A key risk is that the net-zero movement results in a subset of leading investors with greener portfolios, while the broader economy remains largely unchanged. AP2, for example, points out that of the 70% drop in the carbon footprint of its portfolio between 2019 and 2020, less than 4% came from changes to companies’ footprints, with the rest coming from changes in portfolio holdings.[18]

As noted by the NZAOA in the second edition of its Target Setting Protocol, each time an investor adopts a net-zero emissions target while the global economy does not move in conjunction, the gap between the two widens:

“Eventually […] this will force members to divest from entire sectors to bring their portfolios in line with the set target range and reduce the flow of capital to those highly capital-intensive sectors which require financing to transition (such as aviation, transport, and materials).

“This outcome would be highly harmful to the speed of the planetary transition to net zero as the real economy is left behind, hence limiting the real impact on global warming. [Investors] can only de-couple from the real economy benchmark to a certain extent before [their] portfolios no longer reflect the sectors, of which, a net-zero economy would be comprised.”

Investors that divest from high-emitting holdings may free up capital they can reallocate to help bridge the climate financing gap. Yet for allocations that remain within secondary markets, supporting the acceleration of high-emitting companies’ transition plans through stewardship activities will be among the most impactful actions that investors can take.

They can do this individually and through participation in initiatives such as Climate Action 100+. This will be particularly important for companies in hard-to-abate sectors.

Such companies will need shareholders supportive of and forcefully pushing for ambitious decarbonisation timetables.[19]

Shareholders will need to ensure boards of directors are aligned with their long-term interests, by actively challenging and shaping them to have adequate climate competence and oversight.[20]

A disengaged shareholder base may lead to slower private sector decarbonisation, frustrated internal company change agents and continued lobbying practices that prevent necessary policy changes.

With respect to interim decarbonisation targets, investors need to be cognisant of the risk of hitting the target but missing the point. For example, some national governments have been criticised for increasing natural gas use to reduce emissions in the short term while locking in long-term emissions.[21] Investors should similarly be wary of taking actions today that will enable them to achieve interim targets but reduce the prospects of achieving systemic change.

Not all companies will have viable options to transition to a low-carbon economy. Investors in such companies will need to consider whether a managed decline of assets or public policy change are more likely to lead to decarbonisation aligned with the Paris Agreement.

Where investors have sufficient influence with a company, they may be able to agree on a new capital management plan, where it ceases investment in new fossil fuel projects and instead returns capital to shareholders via increased dividends and invests in a just transition for workers and communities.[22]

Yet this may be more effectively achieved via policy change, and a policy engagement strategy is an important component of a net-zero commitment. [23]

Where an investor does miss an interim net-zero target due to continued ownership of high-polluting companies, it should be able to evidence its ongoing stewardship activities with them, including the metrics used to measure such efforts.

Company divestment decisions require scrutiny

Similar considerations apply to how investors appraise companies’ own divestment decisions. While a listed company spinning off a polluting asset may eliminate emissions from its balance sheet, it is unlikely to translate to a reduction in real-world emissions. In fact, it may reduce transparency and accountability over how the asset is managed, result in higher absolute emissions from more intensive exploitation of the asset, and shift risk onto governments and taxpayers.[24] Investors should consider whether and how divestment decisions link to a real-world emissions reduction plan when considering whether to support such proposals.

Addressing greenwashing concerns

This section summarises how a robust, transparent approach to escalation – in divestment or engagement – can help address concerns of investor greenwashing.

Demonstrating their commitment to sustainability outcomes can be difficult for listed equity investors, with both divestment and engagement approaches raising potential concerns of greenwashing.

For the former, an investor may improve the sustainability characteristics of its portfolio without any effect on real-world outcomes, which raises concerns where this is framed as having a positive impact.

For the latter, an investor’s purported commitment to engaging on sustainability outcomes may not be reflected in its actual engagement and voting activities.

In both cases, investors can demonstrate their efforts to affect real-world sustainability outcomes by embedding a range of levers and escalation measures in their stewardship policies and practices and reporting publicly on progress.

Figure 3: Priority elements of a pre-divestment stewardship strategy

- Engage directly with the company to address the relevant issue

- Join or form a collaborative stewardship initiative that includes the company as an engagement target

- File, co-file or support a shareholder proposal[25] setting expectations for sustainability performance improvements

- Vote against relevant members of the board of directors and disclose the rationale for doing so

- Consider shareholder litigation in respect of the company’s failure to address the issue

Where an investor determines that divestment is the most effective way of achieving its objectives, there are steps it can take to improve the chances of affecting sustainability outcomes in the real world, which together could be considered a form of responsible divestment. These include:

- reserving divestment for target companies where other escalation measures have been exhausted (see Figure 3), as this strengthens the signalling effect of that decision;

- publicly disclosing the rationale for a divestment decision;

- where relevant, publishing suggested improvements to a company’s sustainability performance, commitments or governance that would lead to reinvestment and continuing to engage with them post-divestment on that basis; and

- allocating divestment proceeds to activities that more directly contribute to improving real-world sustainability outcomes, thus contributing to a change in the financing cost or liquidity of such activities.[26]

Where a divestment campaign has already gained substantial prominence, further divestment announcements may add little to market information or public discourse, and so employing a broader range of stewardship activities will be necessary for an investor to have an impact.

Deploying broader influence

This section summarises complementary levers investors can use to shape sustainability outcomes beyond direct stewardship of investee companies.

Proponents of divestment and engagement agree on one thing: using one approach in isolation will not be enough to eliminate the risks posed by systemic issues and to achieve ambitious sustainability goals such as the Paris Agreement or the Sustainable Development Goals.

As such, investors wishing to shape sustainability outcomes will need to consider other stewardship levers at their disposal, going beyond direct stewardship of their investees to influencing the market in which they operate.

Engage policy makers

Public policy critically affects the ability of institutional investors to generate sustainable returns and create value. It also affects the sustainability and stability of financial markets, as well as social, environmental and economic systems.

Policy engagement by institutional investors is therefore a natural and necessary extension of their responsibilities and fiduciary duties to the interests of beneficiaries. A failure to implement policies consistent with global sustainability goals and targets may put beneficiary benefits at risk.

Investors should consider whether and how policy change can play a role in supporting progress on an ESG issue and incorporate a policy engagement strategy into their stewardship approach.

The PRI provides resources, updates and guidance to support investors’ policy engagement efforts. With respect to climate change, the PRI has produced briefings on priority decarbonisation policies that investors can support in China, EU, Japan, UK and US.

Engage stock exchanges and index providers

One barrier to the impact of individual investor divestment decisions is that the rise of passive investing has created permanent buyers of listed company stocks that belong to mainstream indices.

Investors seeking to alter unsustainable companies’ access to capital and/or public perception may consider engaging with index providers and stock exchanges to delist or exclude companies that fail to achieve a minimum threshold of sustainability performance from widely-tracked indices – as has happened in reaction to corporate governance concerns. [27]

Many index providers already offer alternative indices that exclude companies based on ESG characteristics. [28] Yet failing to integrate major risks stemming from ESG issues into the most widely tracked indices may reinforce unsustainable market features and exacerbate those risks.

Downloads

References

[1] ESG Today (2021), How to craft an impactful ESG resolution.

[2] https://divestmentdatabase.org/

[3] PRI (2018), Why and how investors can respond to income inequality.

[4] For example, see: Broccardo, Hart and Zingales (2020), Exit vs. voice; Berk and van Binsbergen (2021), The impact of impact investing, Teoh, Welch and Wazzan (1996), The Effect of Socially Activist Investment Policies on the Financial Markets: Evidence from the South African Boycott. For a literature review, see Kölbel et al (2020), Can Sustainable Investing Save the World? Reviewing the Mechanisms of Investor Impact.

[5] Rohleder, Winkels and Zink (forthcoming), The Effects of Mutual Fund Decarbonization on Stock Prices and Carbon Emissions.

[6] EDHEC-Risk Institute (2021), Active ownership as a tool of greenwashing.

[7] See, for example, Responsible Investor (2021), ABP to ditch fossil fuels as investors rule out firms with limited engagement potential.

[8] Financial Times (2021), Hedge funds cash in as green investors dump energy stocks; Serafeim (2021), ESG: Hyperboles and reality.

[9] Responsible Investor (2021), Mutual fund support drives record breaking year for ESG proposals in US.

[10] PRI (2020), Introduction to responsible investment: Screening.

[11] Responsible Investor (2021), UK green pensions campaign branded “misleading” and “unethical”.

[12] See for example Ninety One (2021), Investors pushing the drive to net zero.

[13] Investment Magazine (2021), YFYS performance test: Implications for ESG

[14] PRI Awards 2020, Winner, Stewardship project of the year.

[15] PRI (2021), MN: Collaborating through Platform Living Wage Financials.

[16] IPE (2020), Lothian adopts ‘Engage our equities, deny our debt’ mantra on climate.

[17] In the context of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the term leverage is used to refer to the ability of a business enterprise to effect change in the wrongful practices of another party that is causing or contributing to an adverse human rights impact. See PRI (2020), Why and how investors should act on human rights, pg 14.

[18] AP2, Sustainability Report 2020, pg 36.

[19] See Ceccarelli et al (2022), Which Institutional Investors Drive Corporate Sustainability?, which argues that the presence of a small number of leading investors in a company’s shareholder base alone explains improved environmental and social performance.

[20] PRI (2021), How should responsible investors secure better boards.

[21] NRDC (2020), Sailing to nowhere: Liquefied natural gas is not an effective climate strategy. International Energy Agency (2021), Net zero by 2050: A roadmap for the energy sector.

[22] See Wall Street Journal (2021), Investors balk at plan to buy coal mines and close them, for challenges with this approach.

[23] See forecasted policy change under the inevitable policy response project, and UN-convened Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance (2022), Target setting protocol: Second edition, pg 69.

[24] Bloomberg (2021), What happens when an oil giant walks away.

[25] ESG Today (2021), How to craft an impactful ESG resolution.

[26] UN-convened Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance (2022), Target setting protocol: Second edition, pg 21.

[27] On index exclusions, see Reuters (2017), S&P 500 to exclude Snap after voting rights debate. On delisting, see, for example, The Guardian (2019), Labour weighs up delisting UK firms if they fail to fight climate change.

[28] Responsible Investor (2021), DWS says engaging with index providers will be important part of Net Zero shift.