By Rieneke Slager, University of Groningen and Jean-Pascal Gond, City, University of London

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) ratings are key to responsible investing, but their proliferation has generated concerns about their reliability and validity for investment practice and academic research. We hear lots of corporate managers complaining about ESG ratings but little is known about how they deal with them. We find that corporate use (or misuse) of ratings can provide insights into company decisions and the accuracy of their reporting to third-party data providers.

How are ESG ratings resisted and/or mobilised by managers?

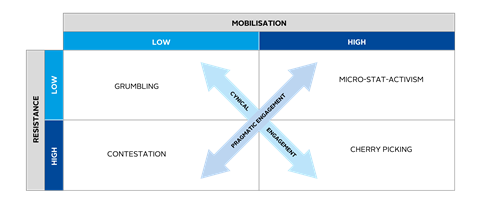

In our paper, The Politics of Reactivity: Ambivalence in corporate responses to corporate social responsibility ratings, we address this question by relying on the qualitative analysis of 63 interviews with 75 managers from 60 companies, and we found four response types:

- Grumbling was the most evidenced response. It reflects the managerial fatigue inherent to filling in questionnaires from multiple ESG rating agencies and consists of complaining about the work overload generated by these activities or questioning their usefulness.

“[The ESG rating agencies] claim to have the ear of some investors, as a sort of benchmark study for them to see how good different companies are. I seriously question that, and if it were just me, and not the company I worked for, I would actually be more resistant and stop filling them in.” (MNC 6)

- Contesting seeks to directly confront the practice of ESG ratings and involves using sophisticated arguments to actively criticise and resist ESG ratings. We found managers questioning either the capacity for ratings to measure their corporation’s ESG performance – focusing their critique on the accuracy, methodological rigour and robustness of rating practices – or critiquing the application of rating criteria to their corporation’s performance. This second type of contestation was often voiced by managers of conglomerates, who felt penalised by the one-size-fits-all template of ESG rating agencies.

“We are lumped into a sector that doesn’t quite fit for us […] to really be reflective of our company it is very hard for these rating agencies to understand what we do.” (MNC 4)

- Cherry-picking is performed by deciding to selectively engage with specific ESG ratings and/or with their sub-dimensions. One form of cherry-picking involves benefiting from the plurality of ratings. When considering which ESG ratings to respond to, managers will weigh up their characteristics, such as their legitimacy, the saliency of their clients and their expected performance, and the fit between rating criteria and ESG strategies and policies. Another form is gaming – by electing specific rating inputs and/or outputs. For instance, one manager recounts that if rating criteria are not considered relevant and no accurate company-level data exist, more limited information is provided to the rating agency, rather than spending resources gathering company-level data:

“[…] we try to temper what we give and we try to be as helpful as we can to Dow Jones, the FTSE4Good and for other compilers of indices but not necessarily going to the lengths that they might want us to go to.” (MNC 19)

In relation to rating outputs, gaming involves selectively communicating only on the best ratings externally – several companies from our sample only report the dimensions of ESG ratings in which they dominate their peers.

- Microstatactivism refers to a fourth response that describes managers mobilising ESG ratings for internal political purpose. The term is derived from the concept of statactivism (a portmanteau of statistics and activism), coined by sociologists, which describes activists’ use of statistics for political purpose. Microstatactivism can involve mobilising ESG ratings as benchmarks against peers or to track performance over time with the aim of improving performance and actively lobbying upper echelons. We found bad and good ESG ratings to be equally useful for corporate managers, as ESG underperformance can justify an increase in resources, while good ESG ratings can help managers to maintain access to resources or improve their status within the company.

“I may have referred to [the ESG ratings] in the past, as an indication of what we need to do to meet best practice or meet internationally accepted benchmarks. I do use it as a point of influence.” (MNC 58)

As illustrated by Figure 1, the four managerial responses to ESG ratings involve distinct combinations of resistance or mobilisation. Two combinations, in particular, co-occurred in our sample (see diagonal arrows on Figure 1): pragmatic engagement with ESG ratings combines micro-stat-activism and contestation (found in 45% of cases), aiming to improve the quality of ratings through contestation in order to consolidate their internal political use; and more cynical engagement, which combines grumbling and cherry-picking (also found in 45% of cases), criticises ratings and utilises gaming to manage their consequences.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that closer attention should be paid to what corporate managers – and potentially other actors – do with ESG ratings. Researchers can better understand how such ratings can trigger internal changes or capital allocations, ESG rating agencies can get a sense of how useful their ratings are to managers and how truthful managers are when they provide data, and investors and regulators may want to further evaluate the regulatory potential of such tools. Future studies on how these groups use ESG ratings in practice could progress our understanding of their (un)intended uses.

This blog is written by academic guest contributors. Our goal is to contribute to the broader debate around topical issues and to help showcase research in support of our signatories and the wider community.

Please note that although you can expect to find some posts here that broadly accord with the PRI’s official views, the blog authors write in their individual capacity and there is no “house view”. Nor do the views and opinions expressed on this blog constitute financial or other professional advice.

If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected]