Ferraro and Beunza analyse data on shareholder engagements from a faith-based coalition (ICCR, Interfaith Center for Corporate Responsibility) to develop a process model for dialogue.

Winner of the Sustainalytics Prize for Excellence in Responsible Investment Research BEST PAPER

Fabrizio Ferraro, IESE Business School and Daniel Beunza, London School of Economics

Key findings

- An iterative dialogue over time may lead to corporate change.

- Raising awareness, building coalitions and reframing issues are key parts of the process.

- Effective dialogue requires communication skills and commitment.

- This study may serve as a blueprint for effective shareholder dialogue.

While shareholder engagement with corporate managers is recognised to have a positive impact, very little is understood about the mechanisms that make it happen. Ferraro and Beunza seek to answer: how does stakeholder dialogue translate into organisational change?

Shareholder engagement is characterised by filing shareholder resolutions to address social or environmental concerns, often accompanied by private dialogue. Success includes withdrawing the resolution and continuing dialogue.

Previous research has mainly addressed an activist approach to filing shareholder resolutions, focusing on reputational threats with the potential of endangering dialogue. Emerging literature acknowledges dialogue is growing in importance and takes expertise. Ferraro and Beunza observe a process model will help guide future engagements.

Analysis

The researchers spent four years examining ICCR records dating back to 1993; conducting interviews with ICCR members, staff and corporates as well as witnessing ICCR members engage in dialogue with corporate managers. To build their theory, the authors selected six companies ICCR had engaged with for 10 years or more. In addition, the companies were diversified by industry and issue. Investors were instrumental in influencing change in three of the engagements (Wal-Mart, Merck, Ford) and ineffective in the other three engagements (ExxonMobil, Dillard’s, Tyson).

The authors note the nature of engagement dialogue has changed over time since the early 1970s when ICCR was founded. Early engagements rarely included dialogue, and this began to change in the 1990s when companies started to open negotiations. ICCR members recognised attempts to silence issues. Nevertheless, the existence of face-toface meetings altered the conversation and set the stage for future effective dialogue.

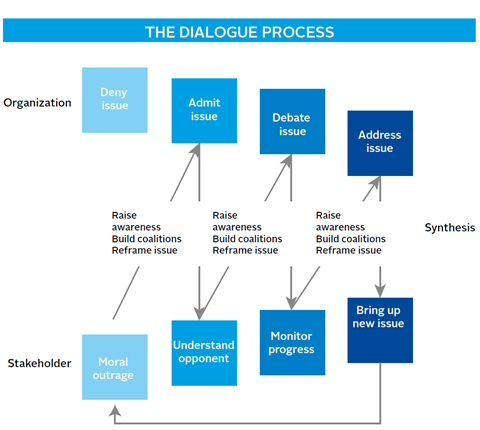

The dialogue process is iterative over time and requires commitment. The authors use case studies to illustrate three elements that occur in all successful cases: raising awareness, building coalitions and reframing issues.

Raising awareness: Wal-Mart case study

ICCR engaged with Wal-Mart on equal opportunity employment rights from 1998 to 2007 resulting in modest changes. The process started with a resolution filed in 1998 that the company challenged at the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), progressed to an initial contentious in person meeting followed by confidential and private dialogue, to result in Wal-Mart publishing its first Equal Employment Opportunities (EEO) report in 2006, disclosing a gender and ethnic breakdown of employees. Also in 2006, ICCR members withdrew a resolution and publicly commended the company.

Due to management changes, a shift in priorities and loss of a key ally, ICCR’s dialogue with Wal-Mart slowed from 2007. In 2011 a Wal-Mart executive joined a conference call and began by ‘apologizing and thanking ICCR “for your 20 years of patience and 20 years of persistence”.’

Over time, ICCR members ‘sensitized’ company managers to employment issues. They created an emotional connection so managers could empathise how ICCR members felt. In addition, ICCR members did not expect immediate acceptance or try to change managers’ thinking. This openness provided the opportunity for managers to consider the issues among themselves. The entire process requires skill honed through practice.

Building coalitions and reframing issues: Merck case study

ICCR’s engagement with Merck occurred from 2001 to 2007 regarding HIV-AIDS and access to medicine in emerging markets. The engagement process started with a letter to the Board of Directors in 2001 requesting Merck to publish a CSR report and disclose policies on HIV-AIDS, filing a resolution in 2003, to Merck publishing its first CSR report in 2003 and agreeing to a conversation. In 2006 ICCR published a benchmarking study of pharmaceutical companies dealing with HIV-AIDS and organised the first ‘Roundtable on Access to Medicine’ in 2008 and another in 2010. Merck launched a new strategy on access to medicine in 2010 that had been developed internally but with feedback from ICCR members. These guiding principles were recognised within the industry and instrumental in Merck being ranked second among global pharmaceutical companies.

The authors identify three traits that distinguish Merck’s dialogue:

- Efforts to meet in person with executives so a discussion within the organisation could be started.

- A non-confrontational and collaborative approach that built trust and comfort.

- Emphasis on general ideas rather than concrete policies in order to set a common ground rather than being prescriptive.

ICCR brought the ‘right people’ to the table, which had an impact on connecting different corporate units that are necessary to address issues that span across the organisation. A critical link is finding internal champions who will support the issue and help transform the company. Going outside the company and including industry peers is also an effective component of building coalitions.

By the nature of being a faith-based coalition, ICCR brings a moral voice. However, it is ICCR members’ status as shareholders that gives them clout to reframe the issues in a business context, which ultimately drives the organisations’ change.

Synthesis

Companies may voice their own response to issues during dialogue, and as part of the iterative process, bring the two sides (activist and company) closer together. This dance of opposing views can eventually be brought together. In the Merck case study, for example, Merck listened to ICCR then queried within the firm what to do with the feedback, and the right approach for the company.

Ineffective dialogues

Dialogue will not be successful with all companies, however. The authors point to examples where ICCR could not build coalitions because there was no controversy within the company of alternative viewpoints. Groupthink crowds out different points of view, a necessary condition for internal debate. With highly contentious issues like climate change (ExxonMobil), there was no room for internal controversy.

Conclusions

The authors put forward seven propositions that encompass the empirical traits and observations made during the case analysis. The propositions address how contentiousness and dialogue relate to one another as shareholder tactics for:

- shaping corporate practices on emerging issues;

- gaining access to corporate management;

- increasing managers’ conviction the contested issue is relevant to their business;

- influencing internal (corporate) debate on the issue;

- influencing the strength of the relationship with the corporation;

- successful dialogue;

- the speed of corporate policy change.

Dialogue is most effective as a transformative, iterative process over a longer period of time. The authors intend this study to serve as a blueprint for effective dialogue.

Download the issue

-

RI Quarterly Vol. 5: Highlights from the PRI Academic Network Conference 2014

November 2014

RI Quarterly Vol. 5: Highlights from the PRI Academic Network Conference 2014

- 1

- 2Currently reading

Why talk? A process model of dialogue in shareholder engagement

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7