Mats Andersson, Patrick Bolton and Frédéric Samama demonstrate that a decarbonised index offers long-term, passive investors a way to hedge climate change risk without sacrificing financial returns.

Hedging Climate Risk with Decarbonised Indexes, Mats Andersson, Patrick Bolton and Frédéric Samama

Andersson et al see existing green indexes as a bet on clean energy rather than a hedge against carbon risk. Their work moves the focus away from the inevitable transition to renewable energy, to concentrate on the timing risk associated with climate policy. The underlying premise is that financial markets currently under-price carbon risk, but that while at some point that will change, predicting the timing of the future climate mitigation policies, which will drive that change, is a key challenge.

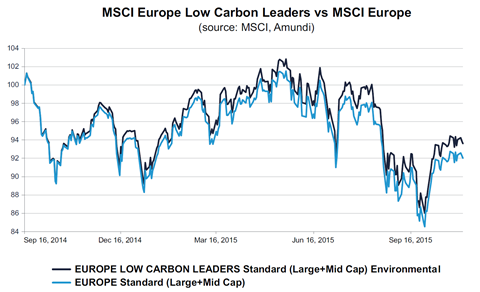

The authors show that a decarbonised index (one that takes a standard benchmark, such as the MSCI Europe in the figure below, and removes or underweights companies with relatively high carbon footprints) can match benchmark returns prior to the introduction of global CO2 emissions limits, and once CO2 emissions limits are expected to be introduced, outperform the benchmark, effectively giving investors what the authors call a “free option on carbon”.

To keep a similar aggregate risk exposure as the standard market benchmark , the authors work with a constraint on the maximum allowable tracking error (how closely the portfolio follows the index to which it is benchmarked) before decarbonising it by divesting from any companies that have a carbon footprint exceeding a given threshold.

Whilst less carbon exposure could be achieved by taking greater risks, this strategy errs on the side of caution to provide stable, long-term returns while limiting active stock trading.

Filtering stocks on a sector-by-sector basis maintains a similar sector composition as the benchmark, with the added benefit of fostering competition between companies within each sector to reduce their carbon emissions. Different filters can be used to normalise companies’ carbon footprints to reflect their energy efficiency/wastage and sector peculiarities, for example dividing CO2 emissions by: tons of output in the oil and gas sector, sales per kilometre in the transport sector, total GWh electricity production in the electricity utility sector, or total sales in the retail sector.

Effect on companies and governments

Reviewing the index annually and clearly communicating which stocks are included or excluded should foster competition, rewarding the included companies and putting pressure on those left out to reduce their carbon footprint and join or re-join the index. Governments can act as a catalyst to accelerate the mainstream adoption of these indexes by pushing public asset owners (public pension funds, sovereign wealth funds) to invest in them.

Case study: AP4

The Fourth Swedish National Pension Fund (AP4) was the first institutional investor to adopt decarbonised indexes on a significant scale. It used a decarbonised index based on the S&P 500 and reduced the overall carbon footprint by 50%. Since first investing in November 2012, AP4’s S&P U.S. Carbon Efficient portfolio has outperformed the S&P 500 benchmark index by 24 basis points annually.

AP4, with the Fonds de Réserve pour les Retraites (FRR) and asset manager Amundi, subsequently worked with MSCI to develop the MSCI Europe Low Carbon Leaders Index, which addresses carbon exposure by excluding the worst performers on carbon emissions and stranded assets. From November 2010 to April 2015, this index delivered an 80 basis point annualised outperformance of the MSCI Europe index that it benchmarks.

Download the issue

-

RI Quarterly vol. 9: Investing in a low-carbon world

December 2015

RI Quarterly vol. 9: Investing in a low-carbon world

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

Currently reading

Currently readingDecarbonised indexes can help hedge climate risk

- 5

- 6